Christmas

A great deal of what we consider integral parts of a traditional Christmas were actually invented through commercial venues. Our “traditional” image of Santa Claus (i.e., overweight, with a flowing white beard, dressed in red, with black boots,

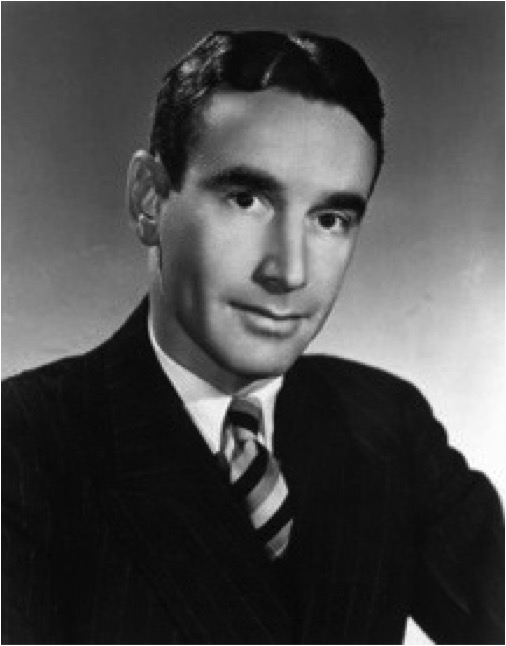

a wide black belt) was originally created as part of a 1930s advertising campaign for Coca Cola. Similarly, the ever-popular Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer was created in 1939 by an advertising copywriter for Montgomery Ward. But there’s a lot more to the story of Rudolph, and his creator, Robert L. May.

Once upon a time, Bob May, a 34-year-old writer for Montgomery Ward in Chicago was not feeling much comfort or joy as the 1938 holiday season approached. He was exhausted and nearly broke. His wife, Evelyn, was bedridden, on the losing end of a two-year battle with cancer. This left Bob to look after their four-year old-daughter, Barbara.

Once upon a time, Bob May, a 34-year-old writer for Montgomery Ward in Chicago was not feeling much comfort or joy as the 1938 holiday season approached. He was exhausted and nearly broke. His wife, Evelyn, was bedridden, on the losing end of a two-year battle with cancer. This left Bob to look after their four-year old-daughter, Barbara.

One night, Barbara asked her father, “Why isn’t my mommy like everybody else’s mommy?” As he struggled to answer his daughter’s question, Bob remembered the pain of his own childhood. Small, sickly, shy, and not well liked as a school boy, he was constantly picked on and called names. But he wanted to give his daughter hope and show her that being different was nothing to be ashamed of. More than that, he wanted her to know that he loved her and would always take care of her.

Influenced by Hans Christian Anderson’s “The Ugly Duckling,” he began to spin a tale about a reindeer with a bright red nose who found a special place on Santa’s team. Barbara loved the story so much that she made her father tell it every night before bedtime. As he did, it grew more elaborate. Because he couldn’t afford to buy his daughter a gift for Christmas, Bob decided to turn the story into a homemade picture book.

Influenced by Hans Christian Anderson’s “The Ugly Duckling,” he began to spin a tale about a reindeer with a bright red nose who found a special place on Santa’s team. Barbara loved the story so much that she made her father tell it every night before bedtime. As he did, it grew more elaborate. Because he couldn’t afford to buy his daughter a gift for Christmas, Bob decided to turn the story into a homemade picture book.

In early December, Bob’s wife died. Though he was heartbroken, he kept working on the book for his daughter. A few days before Christmas, he reluctantly attended a company party at Montgomery Ward. His co-workers encouraged him to share the story he’d written. After he read it, there was a standing ovation. Everyone wanted copies of their own.

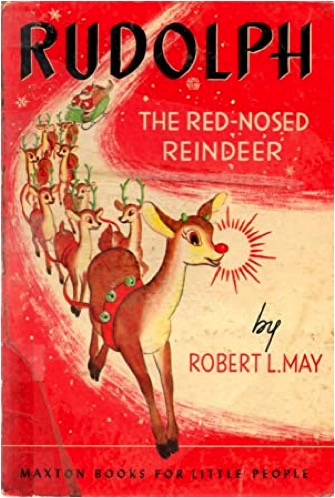

Montgomery Ward bought the rights to the book from their debt-ridden employee. Over the next six years, at Christmas, they gave away six million copies of Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer to shoppers. Every major publishing house in the country was making offers to obtain the book. In an incredible display of good will, the head of the department store returned all rights to Bob May. Four years later, Rudolph had made him into a millionaire.

Montgomery Ward bought the rights to the book from their debt-ridden employee. Over the next six years, at Christmas, they gave away six million copies of Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer to shoppers. Every major publishing house in the country was making offers to obtain the book. In an incredible display of good will, the head of the department store returned all rights to Bob May. Four years later, Rudolph had made him into a millionaire.

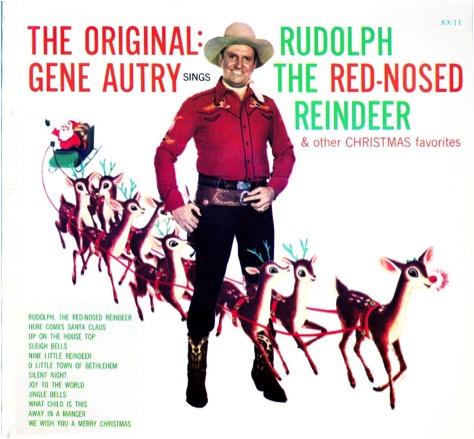

Remarried with a growing family, May felt blessed by his good fortune. But there was more to come. His brother-in-law, a successful songwriter named Johnny Marks, set the uplifting story to music. While there may be a few out there who are still familiar with the Montgomery Ward booklet, or the book that was published after May assumed ownership of Rudolph, most of us are familiar with the story of Rudolph through the song made famous by Gene Autry’s recording [which is quite different from May’s original story].

Marks’ song version was pitched to artists from Bing Crosby on down. They all passed. Finally, Marks approached Gene Autry. The cowboy star had scored a holiday hit with “Here Comes Santa Claus” a few years before. Like the others, Autry wasn’t impressed with the song about the misfit reindeer. Marks begged him to give it a second listen. Autry played it for his wife, Ina. She was so touched by the line “They wouldn’t let poor Rudolph play in any reindeer games” that she insisted her husband record the tune.

Marks’ song version was pitched to artists from Bing Crosby on down. They all passed. Finally, Marks approached Gene Autry. The cowboy star had scored a holiday hit with “Here Comes Santa Claus” a few years before. Like the others, Autry wasn’t impressed with the song about the misfit reindeer. Marks begged him to give it a second listen. Autry played it for his wife, Ina. She was so touched by the line “They wouldn’t let poor Rudolph play in any reindeer games” that she insisted her husband record the tune.

Within a few years, it had become the second best-selling Christmas song ever, right behind “White Christmas.” Since then, Rudolph has come to life in TV specials, cartoons, movies, toys, games, coloring books, greeting cards and even a Ringling Bros. circus act. The little red-nosed reindeer dreamed up by Bob May and immortalized in song by Johnny Marks has come to symbolize Christmas as much as Santa Claus, evergreen trees and presents. As the last line of the song says, “He’ll go down in history.”