May Day

May Day is a celebration that marks a change of seasons, and as such it dates back millenia. The Celts believed that May 1, Beltane, was the most important day of the year. Beltane means “Day of Fire” and they celebrated with large bonfires and dancing. When the Romans came to the British Isles, they brought their celebration of Floralia, a five-day observance of spring and Flora, goddess of flowers, vegetation, and fertility. Floralia encompassed May 1, and eventually Floralia rituals were combined with Beltane.

Self-portrait, frontispiece to Self-portrait, frontispiece to The Adventures of Mr. Verdant Green, 1970 |

One of the popular traditions of May Day is dancing around the May Pole. Historians believe this originated with dances around trees as part of Germanic pagan fertility rituals – a view which would seem to be supported since early Puritans in this county discouraged any May Day celebrations. In Victorian England, however, dancing around a May Pole was considered an important part of May Day celebrations, as was “going a-Maying.”

In 1868, Cuthbert Bede wrote, “For going a-Maying is suggestive of the sweet burst of bud and blossom; the tender mist of green that overspreads the woods; the forest carpet of primroses, violets, hyacinths and anemones; … the snowy bloom of the cherry, plum and blackthorn…. Of a multitude of things, in short that are pleasant, and fragrant, and beautiful, does the phrase ‘going a-Maying’ remind us….” (Along with May Day, Bede also cherished the semicolon).

Going “a-Maying” was practiced at least as early as the Tudor times, when Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon would celebrate with hunting, music and plays. In Elizabethan times, May Day was celebrated with a procession to the village green, headed by the prettiest girl in the village wearing a crown of flowers.

Carrie Beekman, @ age 12. Carrie Beekman, @ age 12.Photo Source: SOHS #267. |

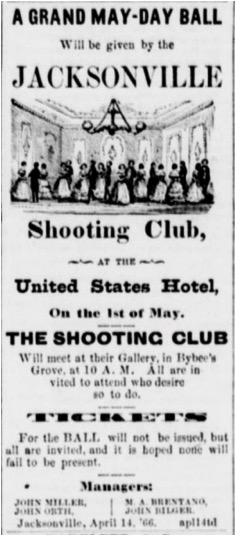

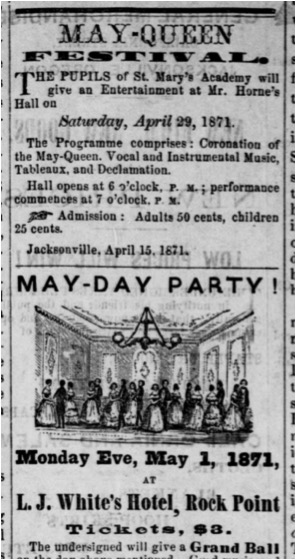

Folks here in Jacksonville celebrated May Day on May 1 with dancing around the Maypole, parades, balls and the choosing of a May Queen, reported on in the local press as far back as 1861.

Folks here in Jacksonville celebrated May Day on May 1 with dancing around the Maypole, parades, balls and the choosing of a May Queen, reported on in the local press as far back as 1861.

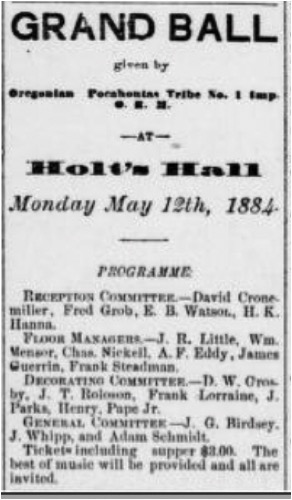

For example, on April 30, 1879, the Oregon Sentinel reported that a May Day Ball was to be held at Viet Schutz’s hall, where the Jacksonville Brass and String Band would perform. Tickets were $1 and the party was open to everyone. The Sentinel also reported that “Miss Carrie,” the eldest daughter of C.C. Beekman, was to be May Queen that year.

“Young folks” were to assemble at the courthouse at 9:30 a.m. for a concert, the crowning of the May Queen, and a procession to “Bybee’s Grove” where there would be more speeches, games and sports.

Many years, evening balls would be held, offering entertainment and food for the price of a ticket, or sometimes even for free.

In the United States, May Basket Day was also celebrated, when baskets of flowers and other treats would be hung on the doorknobs of friends and relatives to celebrate the arrival of spring.

In the United States, May Basket Day was also celebrated, when baskets of flowers and other treats would be hung on the doorknobs of friends and relatives to celebrate the arrival of spring.

During the 19thcentury, May Day became linked with worker’s rights in the United States. On May 1, 1886, more than 300,000 workers walked out of their jobs to protest inhumane working conditions. What followed was strife about which many books have been written, and from which arose new labor unions, the right to humane working conditions, and an eight-hour workday. Ironically, May 1 is recognized as an official workers’ holiday in 66 countries, but not in the United States where it began.

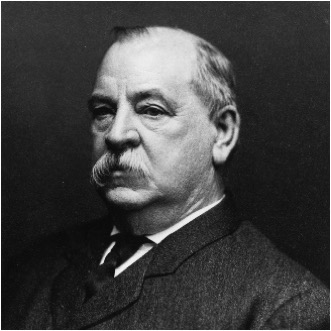

Grover Cleveland. Photo Source:whitehouse.gov |

This is no accident. After the 1894 Pullman Strike was crushed by federal troops, killing thirty people, President Grover Cleveland moved the United States celebration of Labor Day to the first Monday in September. Fearing the rise of communism, he wanted to sever any link to the international worker’s celebration.

Celebrating May Day as a rite of spring has mostly fallen by the wayside; even in 1898, Bede complained that “[e]nough for us are the village school-children with their May ‘garland;’ and even they are only to be found here and there, and in certain counties; and in another generation their pretty and innocent custom may have become extinct.”

Sources Cited:

History.com Editors. “May Day.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 1 May 2017, www.history.com/topics/holidays/history-of-may-day.

Bede, Cuthbert. “Peeps Through Loopholes at Men, Manners and Customs.” Leisure Hour,

1 May 1868, pp. 286–288.

Kemm, Annie. “May-Day Customs.” The Girl’s Own Paper, 1882, pp. 492–494.