|

A Virtual Walk Through Jacksonville History

Stop 16: St. Mary’s Academy and Beekman Square

Let’s stroll a block west on California Street to another site with Beekman’s name on it—Beekman Square—which, ironically, was never part of Beekman’s property. This time we’re paying a virtual visit to a virtual site—the second home of St. Mary’s Academy.

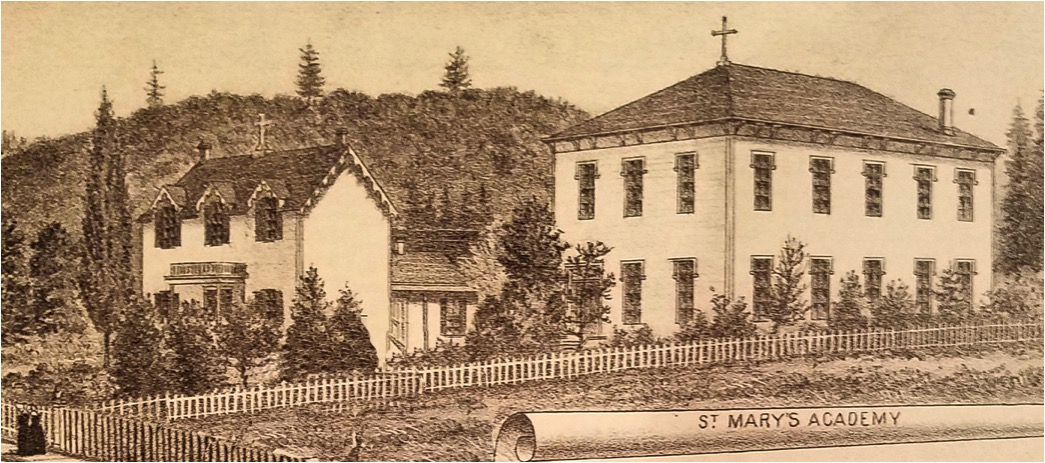

St. Mary’s Academy. Source: West Shore magazine, Portland, OR, August 1883. St. Mary’s Academy. Source: West Shore magazine, Portland, OR, August 1883.

St. Mary’s Academy was established in 1865 after Rev. Francis Xavier Blanchet, priest of St. Joseph’s Catholic Church (Stop #5), asked the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary to open a school in Jacksonville. In August of that year, Sister Mary of the Seven Dolores, Sister Mary Febronia, and Sister Mary Zotique arrived from their convent in Montreal.

Blanchet had collected a total of $2,139 from Jackson County, Josephine County, Del Monte (CA) County, and Fort Klamath and used it to purchase the block bounded by North 5th and 6th and East D and E streets. He spent $642.50 for the property with its two buildings and $1,400 for a piano, leaving less than $100 for furniture. When the Sisters arrived on the evening of August 18, they found their new home had a piano, six chairs, and a table. They spent their first night on the floor on mattresses loaned by neighbors.

The Sisters opened St. Mary’s Academy in the original portion of what is still known as the Catholic Academy building at the corner of 5th and D. They divided the 16-foot by 58-foot one-story structure into five rooms which were used as chapel, parlor, community room, refectory, and classrooms. The house on the adjoining lot became a dormitory for boarders.

Original Catholic Academy Building. Source: Carolyn Kingsnorth Original Catholic Academy Building. Source: Carolyn Kingsnorth

The school opened on September 11, 1865, with one boarding student, a Miss Annie Underwood; by the end of the school year there were 12 boarders and 33 day students.

The Academy prospered for the next few years until August 1868 when the Asiatic Black Smallpox epidemic struck. The school closed that fall and its 23 boarding students were sent home. The Sisters approached the local Board of Health, offering to take charge of the smallpox hospital. They were politely refused on the grounds that the crisis was not sufficiently great to warrant the Sisters risking their lives. However, by late January 1869, Jacksonville gladly accepted their offer.

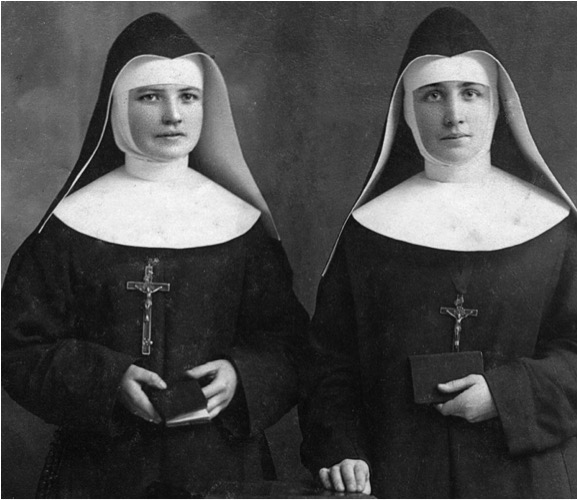

Sisters of the Holy Names. Source: SOHS #129437 Sisters of the Holy Names. Source: SOHS #129437

For the next two months, two of the Sisters visited the homes of the “plague-stricken” day and night, tending to their needs. These nursing Sisters were forbidden to enter other houses, and upon returning to the convent, were not allowed inside. The Mother Superior would hand food and fresh clothing to them and they would repair to a shed on the property to change and eat. When the number of cases subsided in April, convalescing patients were taken to the local hospital and the Sisters were released from their duties. The exhausted nuns found consolation in having baptized a number of patients; they did not try to reopen the school for the remainder of the academic year.

Although the community had not previously been overtly hostile to the Sisters, neither had it been warmly welcoming. The nuns’ actions during the smallpox epidemic won the gratitude of the citizenry and earned the Sisters such tributes as the following:

“It is consoling in a season of public calamity to witness an instance of self-sacrifice like that manifested in the generous offer of the Sisters of the Holy Names….During the epidemic, when strong men shrank in dismay, when the dearest ties of kindred were severed by fear of contagion, the gentle members of the Catholic Sisterhood bravely stepped forward to assuage the horrors of the pestilence….”

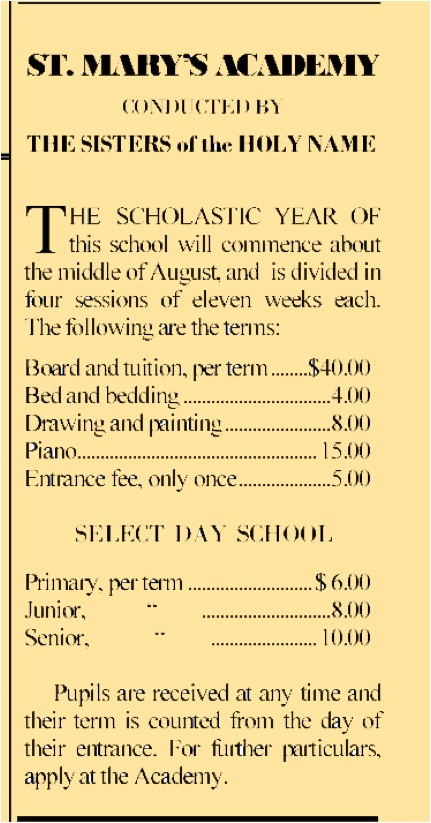

The Sister’s actions also opened the town’s purse strings. We previously mentioned that the early residences along California Street were Jacksonville’s pioneer equivalent of “millionaires’ row.” Having outgrown their existing location, the Sisters of the Holy Names purchased one of those residences in March of 1870, the home of local merchant John S. Drum, for the sum of $2,800 to serve as the location of their second school. To defray the debt they held a parish fair which netted them $1,000 free and clear, “more money than it was thought could be found in Jacksonville.”

St. Mary’s Academy. Source: SOHS #06000 St. Mary’s Academy. Source: SOHS #06000

On April 26, 1870, the Sisters moved into their new convent. The old building which had served as dormitory and senior classroom was also moved to the property. They opened their second St. Mary’s Academy location with four Sisters, 13 boarders, and 39 day pupils.

In 1871, the Academy graduated its first student, Miss Ida Beach. The Oregon Sentinel declared that “No person who listened to her examination…will deny that she most nobly earned her honors…. May the institution furnish many such rich ornaments to society.” The formal graduation ceremony included a march to “Hail Columbia,” a diploma and medals for Miss Beach, a congratulatory from fellow schoolmates, distribution of prizes to other students, more songs, and “Queen Victoria’s Coronation March” for the finale.

1888 Graduating Class. Source: SOHS 07017 1888 Graduating Class. Source: SOHS 07017

The Academy thrived, despite the cancellation of the public school tuition tax in 1875. The public school principal was an opponent of Catholicism and had widely stated “Give me three years and I will annihilate the convent.” In 1880, one of the most successful in St. Mary’s Jacksonville annals, he had to acknowledge the Academy’s increased vitality, and the following year, the Academy erected an additional two-story building.

|

|

From the beginning, boys were admitted to St. Mary’s for elementary studies; high school level classes were offered to girls who were ready for them; and the Academy had flourishing music and art departments. Many not enrolled in regular studies took advantage of the music offerings. More than 50% of the students were from non-Catholic families, although a number of graduates did choose to enter religious life. Graduates included members of Jacksonville’s prominent Bolt, Orth, Bybee, and Britt families among others.

Mollie Britt with Sister Mary. Source: SOHS #07988 Mollie Britt with Sister Mary. Source: SOHS #07988

|

Music Students at St. Mary’s, 1897. Source: SOHS #0925 Music Students at St. Mary’s, 1897. Source: SOHS #0925

However, despite its success and the central role it played in Jacksonville’s educational options for 23 years, the school was closed in 1889. The reasons cited were “lack of spiritual succor” because the priest was away for weeks at a time on mission trips; the demand for teachers elsewhere in larger communities; and the need for major repairs to the buildings which the Sisters were not able to make.

All but two Jacksonville residents signed a petition to the Mother General of the Sisters of the Holy Names asking them to reopen the school. However, it was not until 1891 when boarding students were recruited from Yreka, Klamath, and Red Bluff, that the Academy was able to reopen.

1894-95 saw enrollment of 80 students. 1895-96 saw an increase of four—21 boys and 38 girls as day students and 25 boarders. The average yearly enrollment continued to be from 60 to 70 pupils. However, as Jacksonville’s regional prominence began to wane, other towns sought St. Mary’s favor. Ashland offered five acres of free land, but it was deemed too far away from the principal parish church. The Medford Commercial Club and the Mayor both made their pitch for a Medford site, and in 1908, the Academy relocated to a full block on Medford’s 11th Street. In 1961, a separate high school was built on Black Oak Drive.

St. Mary’s sold their Jacksonville site to Albert Schmidt, described as one of “the elite of the town.” The Mail Tribune reported Schmidt putting the main building into “first class shape” and residing there with his family until 1924 when they relocated to San Francisco. Two years later in February 1926, the building was “swept by flames” leaving “nothing more than a gaunt framework.”

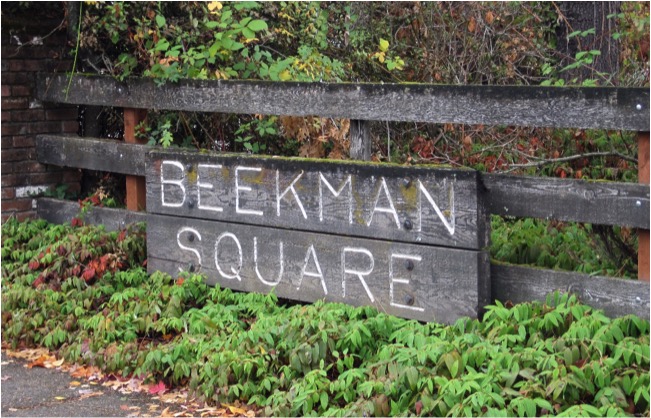

In 1968 the neighboring 100-year-old house of Alexander Martin, another early wealthy pioneer and partner of John Drum (the original owner of St. Mary’s second Academy), was demolished with the permission of the Jacksonville Planning Commission along with the home of a third partner, John Glen, to make way for what we now know as Beekman Square.

Sources Cited

Scrapbook, Sacred Heart Church, Medford, OR, 1982.

Notes, St. Josephs Catholic Church, Jacksonville, OR.

“School Change,” Democratic Times¸ June 13, 1889.

“St. Mary’s Academy,” Democratic Times, June 27, 1889.

“Pioneer Structure at County Seat Swept by Flames,” Mail Tribune, February 26, 1926.

|