| |

A Virtual Walk Through Jacksonville History

Stop 22: John Orth Commercial Building

Now that we’ve visited John Orth’s residence, let’s head a block west and see Orth’s commercial building at 150 South Oregon Street.

1872 Orth Commercial Building. Photo Credit: Carolyn Kingsnorth. 1872 Orth Commercial Building. Photo Credit: Carolyn Kingsnorth.

|

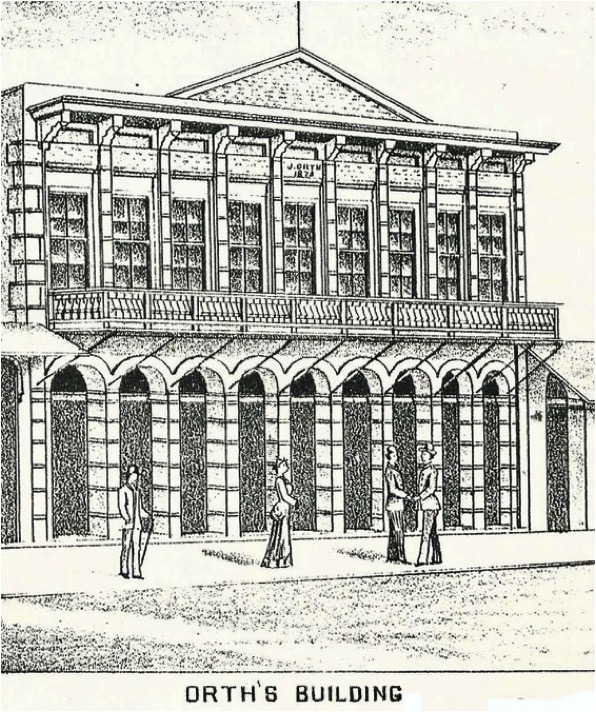

Orth apparently liked the Italianate style of architecture since he chose it for both business and residence. His 1872 commercial building is essentially a two-story brick block with arched ground floor and rectangular second floor windows and doors, separated by pilaster strips. Original drawings show a triangular pediment adorning the roof line. The architect and builder are unknown.

As noted in our previous stop, Orth was born in Bavaria in 1834, emigrated to the U.S. when he was 18, learned the butcher’s trade in Cincinnati, and arrived in Jacksonville by the late 1850s. By 1863, Orth had opened a butcher shop on a portion of the existing building site.

|

| He went on to become the most successful butcher in Jacksonville. Orth was noted for his business acumen, was active in social and civic affairs, served as a city councilor for a number of years, served a term as county treasurer, and was active in fraternal organizations.

The site of the Orth building was originally on the perimeter of the infant gold mining town’s business center on West Main between Oregon and 1st streets. In 1855, the Brunner brothers had constructed at brick dry goods store at the corner of Main and Oregon. A year earlier, the Haines brothers had erected a wooden mercantile building at the opposite corner at California and Oregon streets, which they replaced with a one-story brick structure in 1861.

In between these structures, there apparently were three wood frame buildings. No later than 1853, the Palmetto Bowling Saloon occupied the south portion of the space, providing weary prospectors with a lively

|

John Orth. SOHS # 12573 John Orth. SOHS # 12573

|

Source: 1856 Lithograph of Jacksonville Source: 1856 Lithograph of Jacksonville

|

combination of recreation and relaxation. In November of that year, the “saloon with bowling alleys attached” was sold along with its assemblage of “mirrors, tables, benches, lamps, decanters, and stoves” and renamed the New England Bowling Saloon.

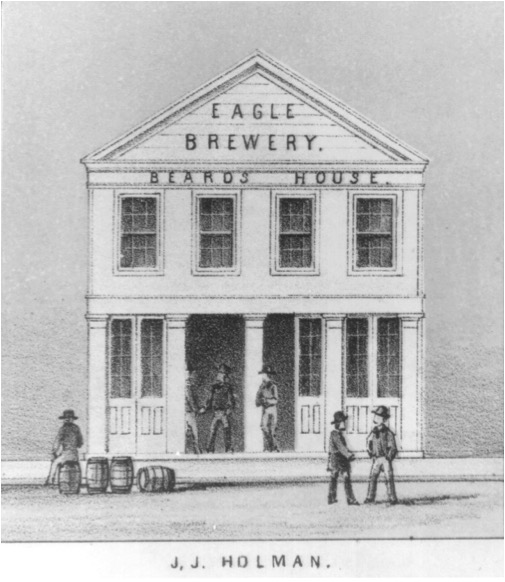

North of the Bowling Saloon was the Holman House and Eagle Brewery, originally owned by J.J. Holman and supposedly built in 1852. This subsequently became the Beard House and then the Old City Brewery (probably more a saloon) when the Eagle Brewery moved to its current location at 355 South Oregon in 1859.

|

Somewhere among the “high spirited atmosphere” was an “old hospital building” occupied first by Dr. Daniel Byrne and later by Dr. Overbeck who dispensed “drugs and chemicals” from the “City Drug Store.”

By 1861, butcher Mathew Ish had purchased at least the southern lot next to the Brunner brothers’ brick edifice along with the privilege of attaching his brick building to the Brunners’. Ish’s plans never materialized and in 1863 Orth bought Ish’s lot and butcher shop. Two years later Orth bought the hospital building site. He completed assembling his parcels in 1872 with the purchase of the Old City Brewery.

That same year Orth erected his three-story brick and stone structure that encompassed all the land between the Brunner building and the Haines brothers’ store. It consisted of a basement storeroom, a ground floor that housed his meat market with additional commercial space, and a hall on the second floor. The cornerstone was laid in July and by year end, construction was almost complete.

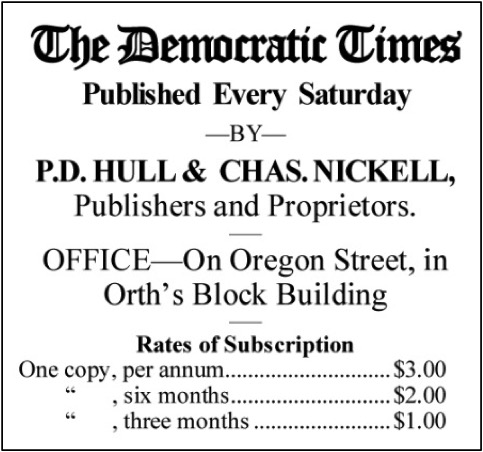

When Orth razed the old buildings to make way for his new one, the Democratic Times lamented the loss of the old, noting that the site had been “devoted to almost every purpose except the printing of a newspaper and serving God.” The newspaper rectified the former omission by taking space in Orth’s new structure When Orth razed the old buildings to make way for his new one, the Democratic Times lamented the loss of the old, noting that the site had been “devoted to almost every purpose except the printing of a newspaper and serving God.” The newspaper rectified the former omission by taking space in Orth’s new structure

Elias Jacobs was one of the first who bid for space in Orth’s building. He subsequently advertised an assortment of “fancy goods, clothing, liquors, tobacco, crockery, etc.” “Hides and produce” were willingly taken in exchange. Soon after, Dr. S.F. Chapin rented the upper floor for a private hospital that could accommodate eight patients. William Hoffman also established his office there.

By 1874, the top floor had been converted to the Farmer’s Hotel; attorneys A.C. Jones and H.K. Hanna had offices in the building; and E.C. Brooks operated a drug store. B. Rostal advertised an unusual professional haircutting shop, promising to give “careful treatment of fractures and external diseases.” He also displayed “all kinds of birds stuffed in most natural shapes.”

The Orth building was threatened by fire on three occasions but only the 1888 fire originating in David Linn’s planning mill on the northwest corner of California and Oregon caused any significant damage. That fire destroyed the entire block now occupied by the telephone exchange, post office, and visitors’ center. It jumped California and burned down Jacksonville’s Chinatown, now Veterans’ Park. The Orth building escaped with damage to a portion of its roof.

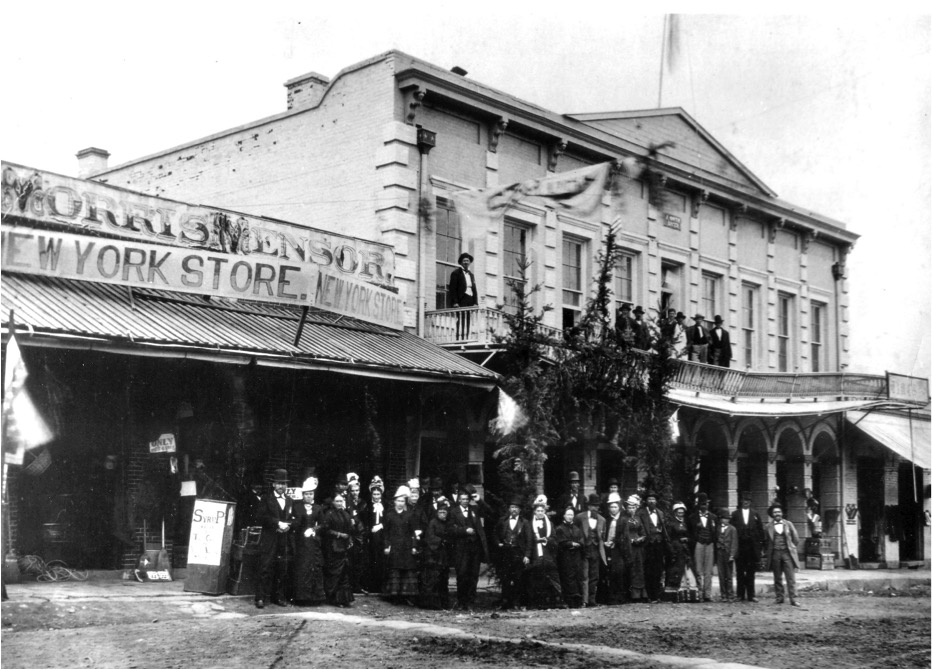

Perhaps more memorable was the Red Men’s St. Tammany’s Day celebration in May of 1880. Jacksonville’s Pocahontas Tribe No. 1 had hosted the Klamath Tribe No. 8 and the Yreka Tribe No. 53 for the occasion. On Thursday, May 13, participants assembled on the balcony of the Orth Building to have their photographs taken. The weight proved too much, and the iron supports gave way, “almost precipitating the living mass to the ground below.” Fortunately, the rope attached to the Red Men’s flagpole had been securely fastened to the railing. It held, supporting the balcony and preventing what might have been a serious catastrophe. The “photo op” caused severe fright, but no one was injured.

Red Men’s St. Tammany’s Day Celebration, May 13, 1880. Photo Source: SOHS #21350 Red Men’s St. Tammany’s Day Celebration, May 13, 1880. Photo Source: SOHS #21350

The balcony was removed shortly thereafter. It was another 100+ years before it was restored.

John Orth’s butcher shop occupied space on the ground level from the time the building was constructed to well into the 1890s. The building’s occupants and uses for the next 50 years are uncertain. However, by the late 1940s the building was devoted to the processing of gladioli bulbs.

Gladioli became a huge “fad” industry in the 1930s, not unlike the Dutch “tulipmania” of the mid-1600s. Our local industry started in Josephine County but soon attracted growers in Jackson County. Warner Gladiolus Gardens became the county’s largest grower, and the Orth Building was William J. Warner’s “factory.” Bulbs brought in from the fields were sorted by size, washed, fumigated to eliminate fungi and insects, and prepared for shipping. The building was used for this purpose well into the 1970s. In fact, Jacksonville has its own namesake gladiolus bulb—”Jacksonville Gold”—still available by mail order today. Gladioli became a huge “fad” industry in the 1930s, not unlike the Dutch “tulipmania” of the mid-1600s. Our local industry started in Josephine County but soon attracted growers in Jackson County. Warner Gladiolus Gardens became the county’s largest grower, and the Orth Building was William J. Warner’s “factory.” Bulbs brought in from the fields were sorted by size, washed, fumigated to eliminate fungi and insects, and prepared for shipping. The building was used for this purpose well into the 1970s. In fact, Jacksonville has its own namesake gladiolus bulb—”Jacksonville Gold”—still available by mail order today.

Sources Cited:

Gail E. H. Evans, Jacksonville History Survey, April 1980.

State of Oregon Inventory of Historic Properties, 1979.

Democratic Times, June 22, 1872.

The Oregon Sentinel, January 3, 1877.

Democratic Times, May 14. 1880.

“Jacksonville Gladioli Growers Harvesting $125,000 Crop,” Medford Mail Tribune, October 9, 1949.

|