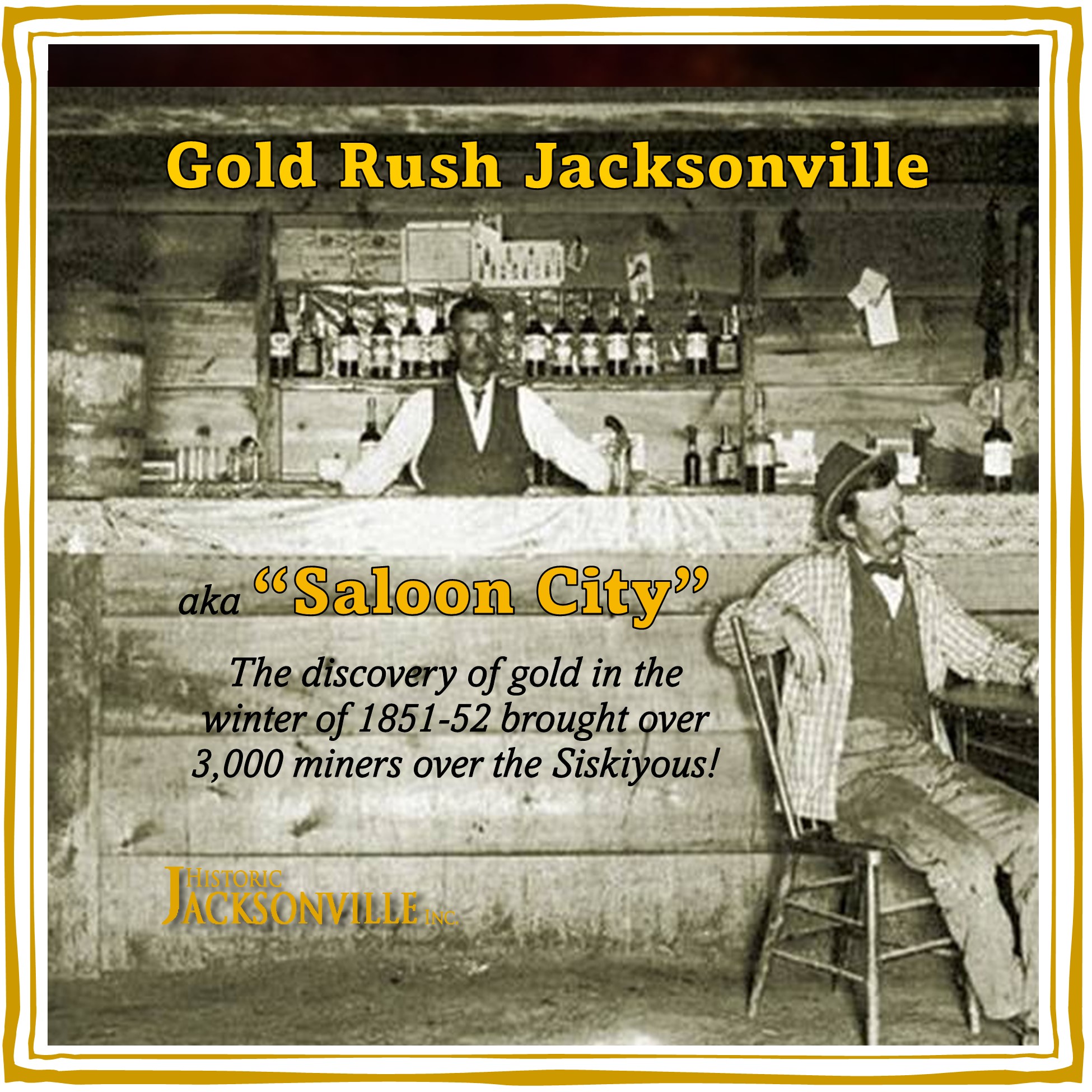

Gold rush Jacksonville allegedly had as many as 36 saloons. Keep in mind, if a merchant sold liquor, he might be considered a “saloon” and for years the Jacksonville Town Council regularly issued liquor licenses because that was their main source of revenue.

But to begin at the beginning….“Saloon City”

Less than 2 months after Clugage and Poole discovered gold in Daisy Creek in the winter of 1851-52, Appler & Kenney, packers from Yreka, opened a tent trading post catering to the “eruption of miners” that rushed to the Rogue Valley. Their “bazaar” was located approximately where Happy Alpaca now stands at the corner of California and Oregon streets. It reportedly maintained a minimal stock of tools, clothing and tobacco, and a liberal supply of whiskey.

W.W. Fowler constructed the community’s first building, a canvas topped log house, near the head of Main, the only street in the embryo city. It was a store cum saloon. Miller’s & Wills’ “round tent” soon became the miners’ destination of choice on any Sunday, their “day of rest.” The tent was a combination of saloon and gambling hall. Jacksonville was well on its way to becoming “Saloon City”….

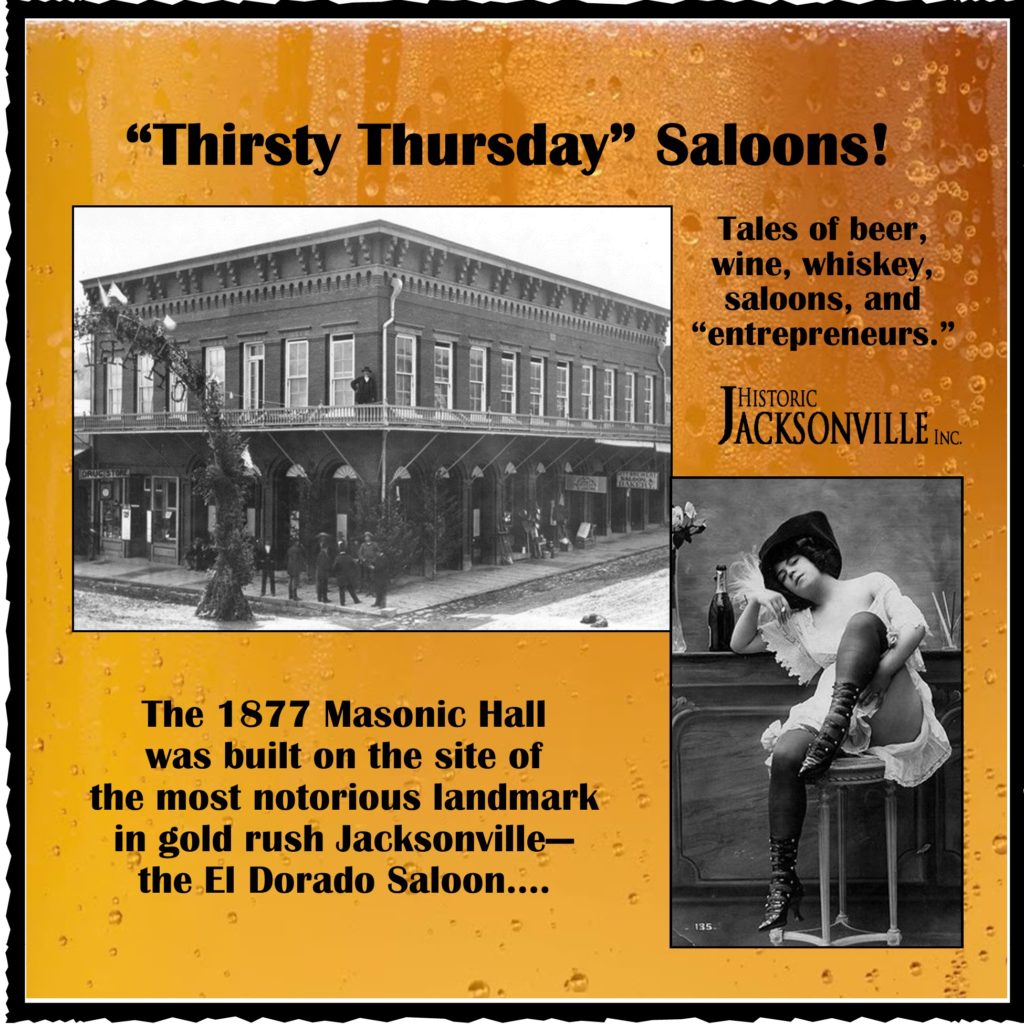

El Dorado Saloon

The 3,000+ miners who followed the discovery of gold in Daisy Creek in the winter of 1851-2 were soon joined by “the class that struck prosperous mining camps like a blight”—gamblers, courtesans, and con men of every kind. Their favorite place of activity was one of the most notorious landmarks in the early mining community—the El Dorado Saloon. By the summer of 1852, this wooden structure occupied the corner of California and Oregon streets. It fronted on Oregon and extended 100 feet along California Street, also housing “club rooms,” a barber shop and baths. Stories of murders, prostitution, gambling, theft, and the like surrounded the El Dorado until its demise by fire in April of 1874.

Soon afterwards, the local Warren Lodge chapter of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons acquired the property and by 1877 they had erected the current Masonic Hall. The building design included ground floor retail space whose rental income funded lodge activities. It should be noted that one of the first building occupants was the City Brewery and Saloon!

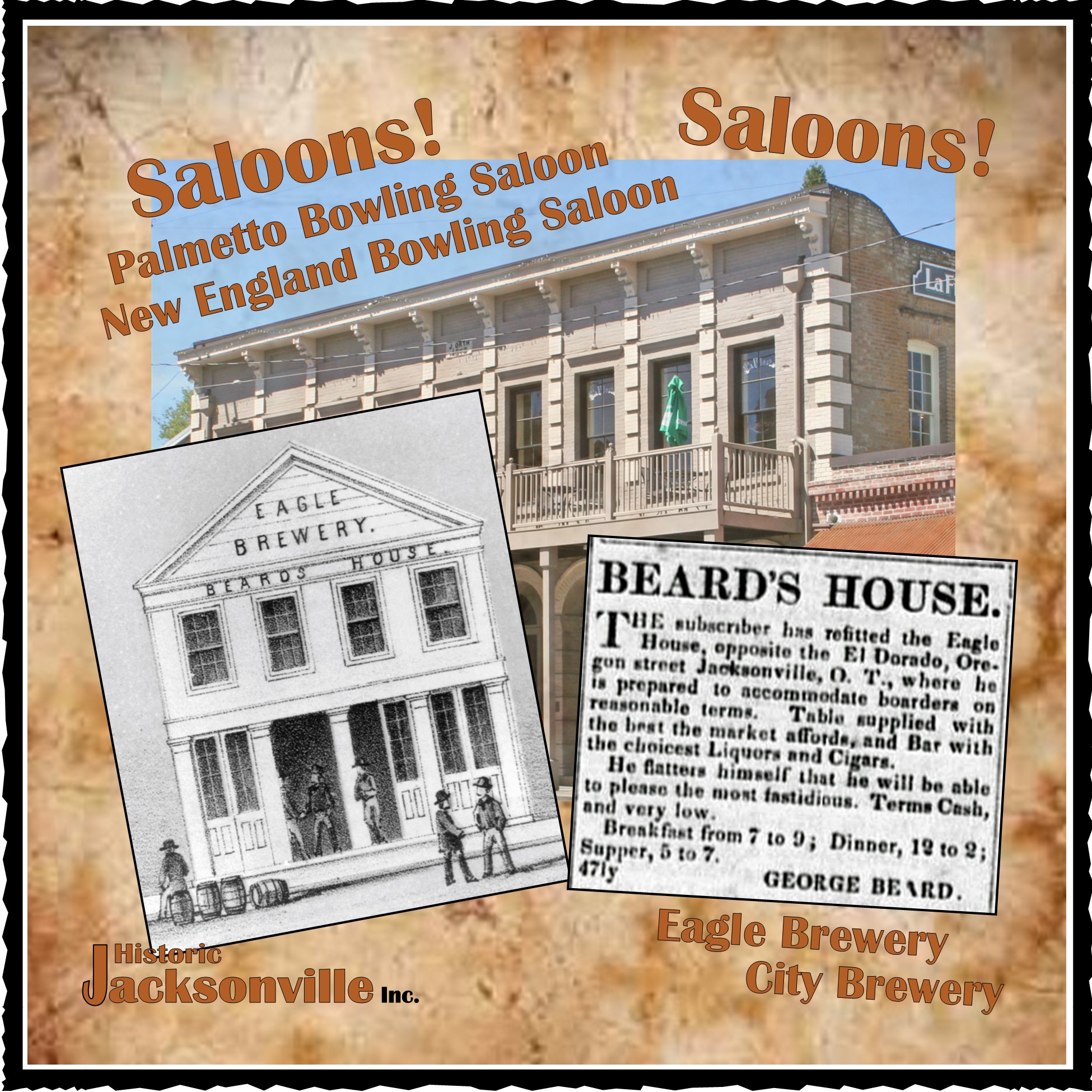

Orth Building Saloons & Brewery

The site where the Orth Building now stands on South Oregon Street originally housed two early Jacksonville saloons. The Palmetto Bowling Saloon was in operation no later than 1853, providing weary prospectors with a lively combination of recreation and relaxation. It was sold in November of that year along with its assemblage of mirrors, tables, benches, lamps, decanters, and stove and renamed the New England Bowling Saloon. Neighboring it was the two-story Classical Revival-style Holman House, later renamed the Beard House. Supposedly built in 1852, it also housed the original Eagle Brewery, later renamed the City Brewery and operated by Veit Schutz, one of the many German-speaking settlers. It’s mentioned as early as March of 1852. Lodged somewhere in the midst of this high spirited atmosphere was an old hospital building and physician’s and surgeon’s office. Given that most medicines of the time tended to have high concentrations of alcohol, opium, or cocaine, they should have fit right in. John Orth razed all of these properties in 1872 to make way for his modern two-story brick building.

Veit Schutz Hall

As you climb the stairs from Highway 238 to the Lower Britt Gardens, have you wondered about the stone walls and cavern you see on your left? For nearly 50 years that was the main entry into what was originally Veit Schutz Hall. Schutz had landed in Jacksonville from Bavaria in 1853. He initially operated the City Brewery on South Oregon, but in 1856 he constructed a 3-story brewery on this site.

One of the largest and grandest buildings in Jacksonville at the time, it also featured a bar and an elaborate dance hall and was the site of many local celebrations and other activities. When Schutz died in 1892, Peter Britt took possession of the property, expanding the operations to include a flourishing wine and trading goods business. After Britt’s death in 1905, the building was abandoned, falling into disrepair. It was torn down in 1953, leaving only the stone foundation and wine tunnel you see now.

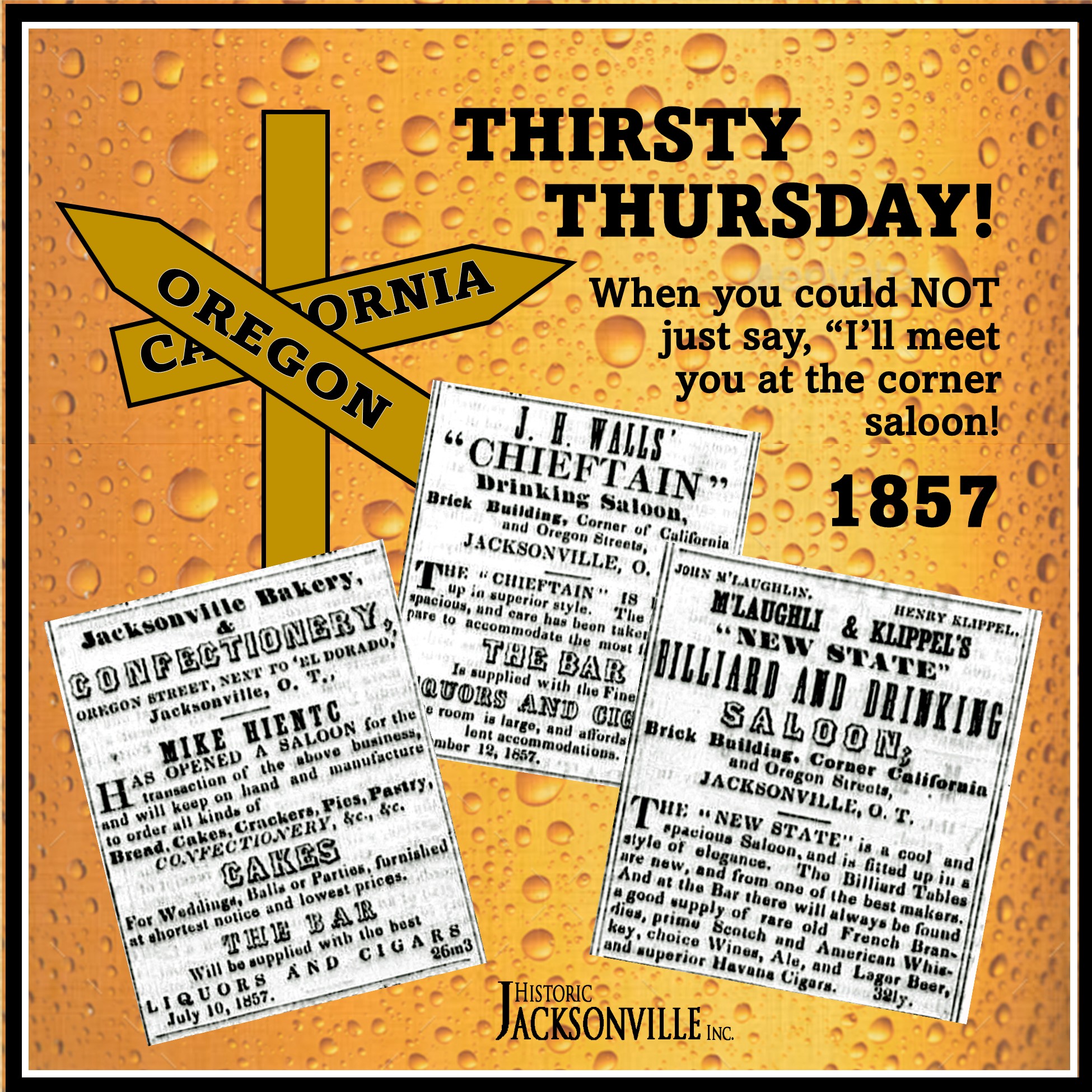

Oregon and California Streets – Saloon Crossroads

The intersection of Oregon and California streets seems to have been a popular crossroads for early Jacksonville saloons. We’ve already mentioned the notorious El Dorado Saloon, the New England Bowling Saloon, and the Eagle Brewery that congregated around that location. No later than 1857 they were joined by the Chieftain Saloon and the New State Billiard and Drinking Saloon. And next door to the El Dorado, the Jacksonville Bakery & Confectionary not only offered sweet treats, it also had its own bar.

Naturally, all of these saloons featured the finest liquor and cigars. The New State made a point of trying to distinguish itself, describing its interior as “cool, spacious, and elegant.” It also boasted of new billiard tables and made a point of citing its “good supply of rare old French Brandies, prime Scotch and American whiskey, choice wines, ale, and Lager Beer, and superior Havana Cigars.”

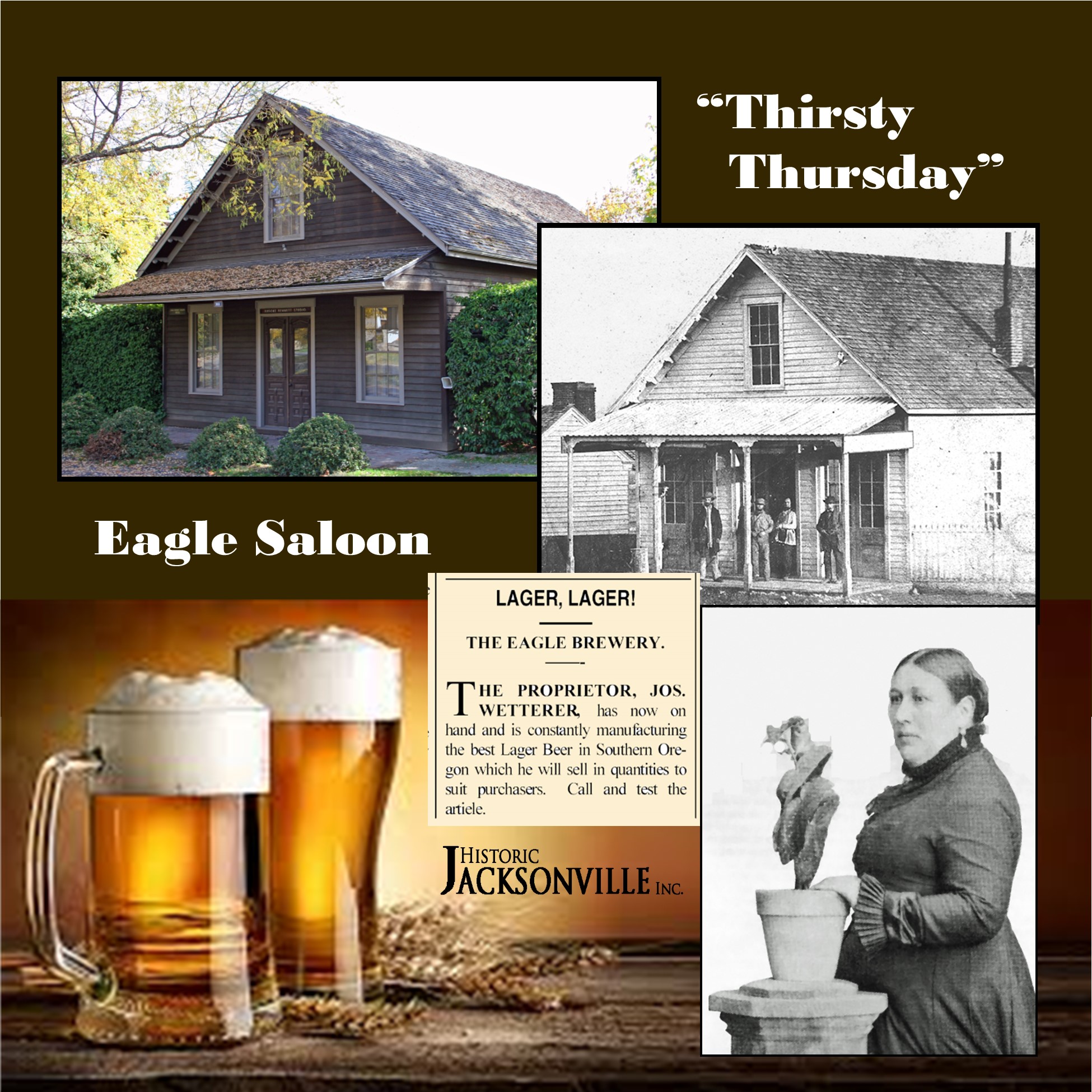

Eagle Brewery and Saloon

The Eagle Brewery was probably Jacksonville’s first brewery, in operation no later than 1856 on the block between Main and California streets that now houses the Orth Building. But by 1859 the Brewery was in existence at its current location, 355 S. Oregon Street, and under the ownership of German-born Joseph Wetterer. Two years later Wetterer “commenced the building of a large beer saloon in front of his brewery.” For the next 18 years, Wetterer and his wife Fredericka ran the saloon, advertising “the best lager beer in Southern Oregon”—even though we can find no trace of Wetterer ever owning a liquor license.

Although the business was successful, when Wetterer died in 1879 he left significant debts for his wife Frederica. The brewery closed in 1880, but her father, Joseph Sage, paid off the mortgage and transferred the property to her the next year. In 1883, she married William Heeley, a former employee, and the brewery was renamed the William and Frederica Heeley Brewery. Fredericka continued operating the brewery for a period after Wetterer’s death in 1879, but by 1892 the Eagle Brewery and its complex of buildings containing the “malt kiln,” “mash tub,” “cooler,” “furnace heat,” and “beer kettle” were no longer in operation. The saloon stood vacant, and the property was labeled “dilapidated” on local maps—marriage, debt, and death having all played their parts in family business management.

Table Rock Billiard Saloon

The Table Rock Billiard Saloon actually began as the Table Rock Bakery, but when German-born Herman von Helms bought out John Wintjen’s partners in October 1858, the Bakery began advertising “The Bar” stocked with a choice lot of liquors, wines, and wholesome lager beer. It appears to have taken over the Oregon Street space previously occupied by the Jacksonville Bakery and Bar next to the El Dorado Saloon.

In 1860 Wintjen and Helms tore down their wooden frame structure and an adjacent building and constructed the arcaded brick building we are familiar with today. Their brick building prevented the 1874 fire that began in the El Dorado Saloon from spreading to Oregon Street although it took out most of its adjacent California Street buildings. It also eliminated the El Dorado, the Table Rock’s closest, and perhaps primary, competition.

The Table Rock Billiard Saloon became a Jacksonville institution for the next 50 years. It served as an informal social and political headquarters, home to business deals, court decisions, and even trials. It was also Jacksonville’s first museum, Helms’ “Cabinet of Curiosities”—a collection of pioneer relics, fossils, and oddities designed to attract a clientele that then stayed for the saloon’s lager. Herman von Helms ran the saloon until his death in 1899; his son Ed operated it until his retirement in 1914.

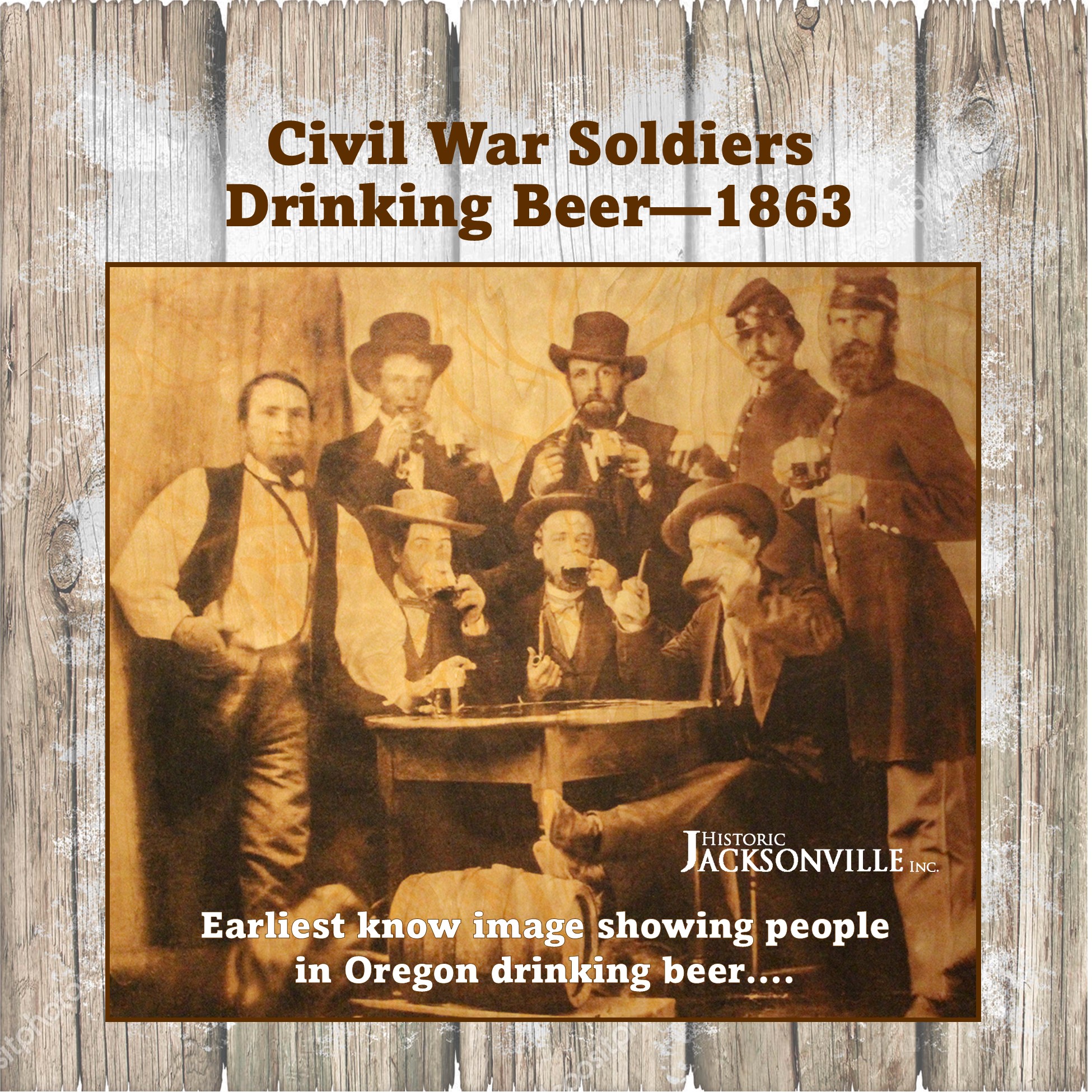

Civil War Soldiers

Even though the Civil War raged from 1861 to 1865, a man still needed a drink—possibly even more so since there was a war on. Today’s image dates to 1863 and shows Civil War soldiers in Jacksonville, most likely at the Eagle Saloon.

Southern Oregon was heavily divided between Confederate and Union sympathies, even causing businesses to close when partners held opposing loyalties. Although we’re not aware of local saloonkeepers expressing strong support for one side or another, they may have done so subtly through their advertising, placing their larger ads in the local newspaper best reflecting their politics. Given that the soldiers shown are wearing Union uniforms, one could guess the Eagle Saloon owners, the Wetterers, were Union supporters.

On a side note, this photo is unique in that it may be the earliest image from Oregon showing people drinking beer.

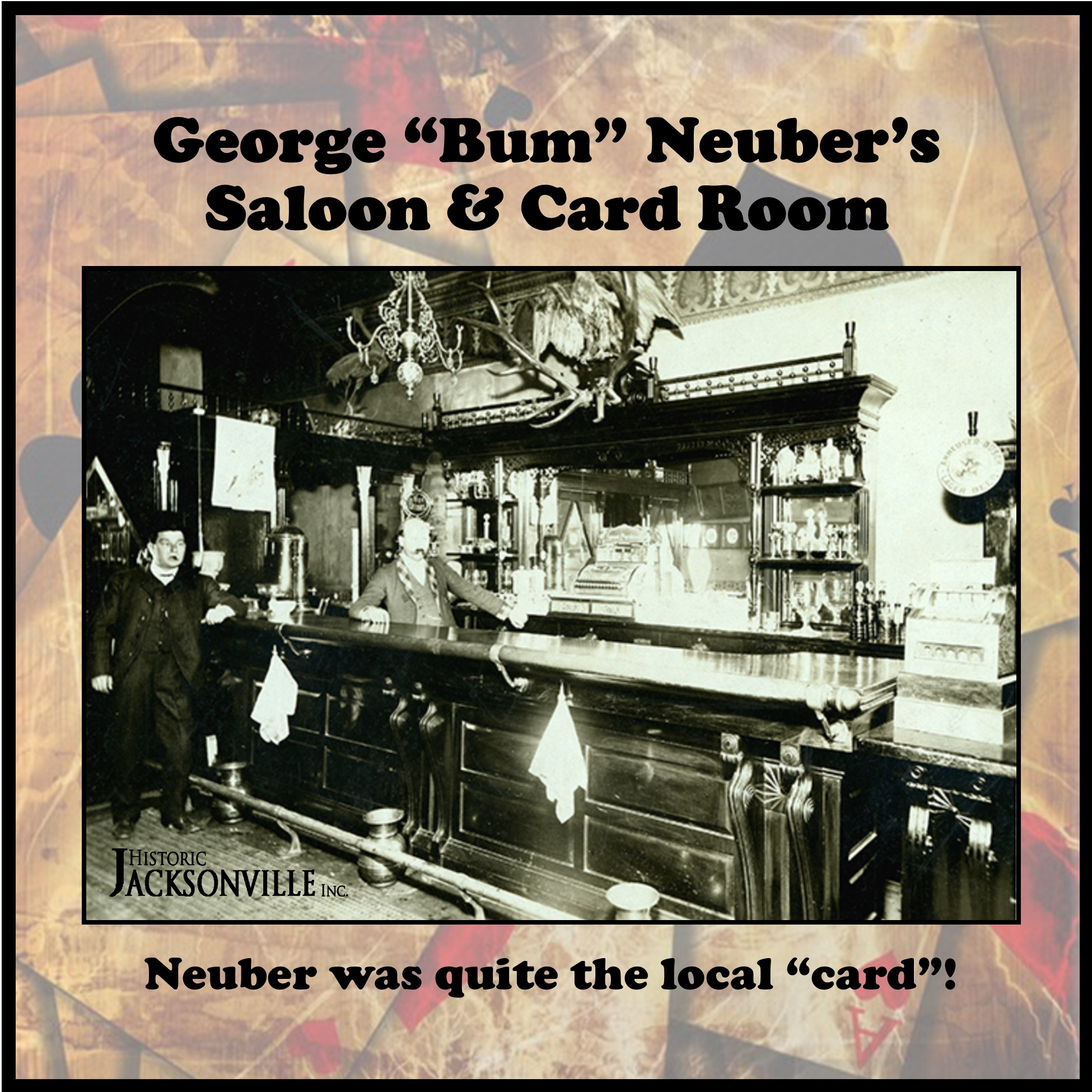

George “Bum” Neuber’s Saloon and Card Room

George “Bum” Neuber (1865–‐1929) was a prankster and a joker. He was responsible for firing the Jacksonville cannon in the 1904 “celebration” that wiped out most of the windows on California Street. He was a “card” in the language of his day, so it seems appropriate that he ran a Jacksonville card room and saloon. Located at 130 W. California Street, his saloon and gaming establishment occupied the same location where his father, John Neuber, had opened the town’s first jewelry shop.

John specialized in solid gold buckles for women’s belts. George specialized in relieving customers of their gold. In addition to his card room and saloon, he also owned the Jacksonville Gold Brick baseball team and was known for bringing in “ringers” to ensure the success of his players.

Bella Union Saloon

The oldest part of the Bella Union Restaurant and Saloon at 170 W. California Street was constructed in 1874 after fire destroyed many of the original buildings in Jacksonville. It replaced a 1-story brick building erected on this site in 1856, also home to a Bella Union Saloon.

From 1864 to 1871, Prussian native Henry Breitbarth operated the original Bella Union, a popular social gathering spot. “Bella Union” was a popular name for drinking and gambling establishments in early mining towns, but it is believed Breitbarth borrowed the name from the infamous San Francisco Bella Union gambling house.

The beginning of the end for Breitbarth’s Bella Union was the 1871 shooting incident between Senator James D. Fay and V.S. Ralls over Ralls’ daughter, Hannah. It seems that Sen. Fay had employed Hannah as housekeeper, but she found her “duties” involved more than keeping house. When Hannah gave birth to an illegitimate child, her father tracked Fay down. Ralls found Fay in the Bella Union, accused him of the seduction of his daughter, and said that one of them must die. Shooting commenced. Fay sustained a flesh wound; Ralls mounted his horse and rode home. Since Fay was a State Senator, the incident made headlines around Oregon.

Although the notorious El Dorado Saloon had been the scene of many shootings and still thrived, apparently the Bella could not so easily brush off the scandal. Breitbarth closed the saloon and moved to Portland.

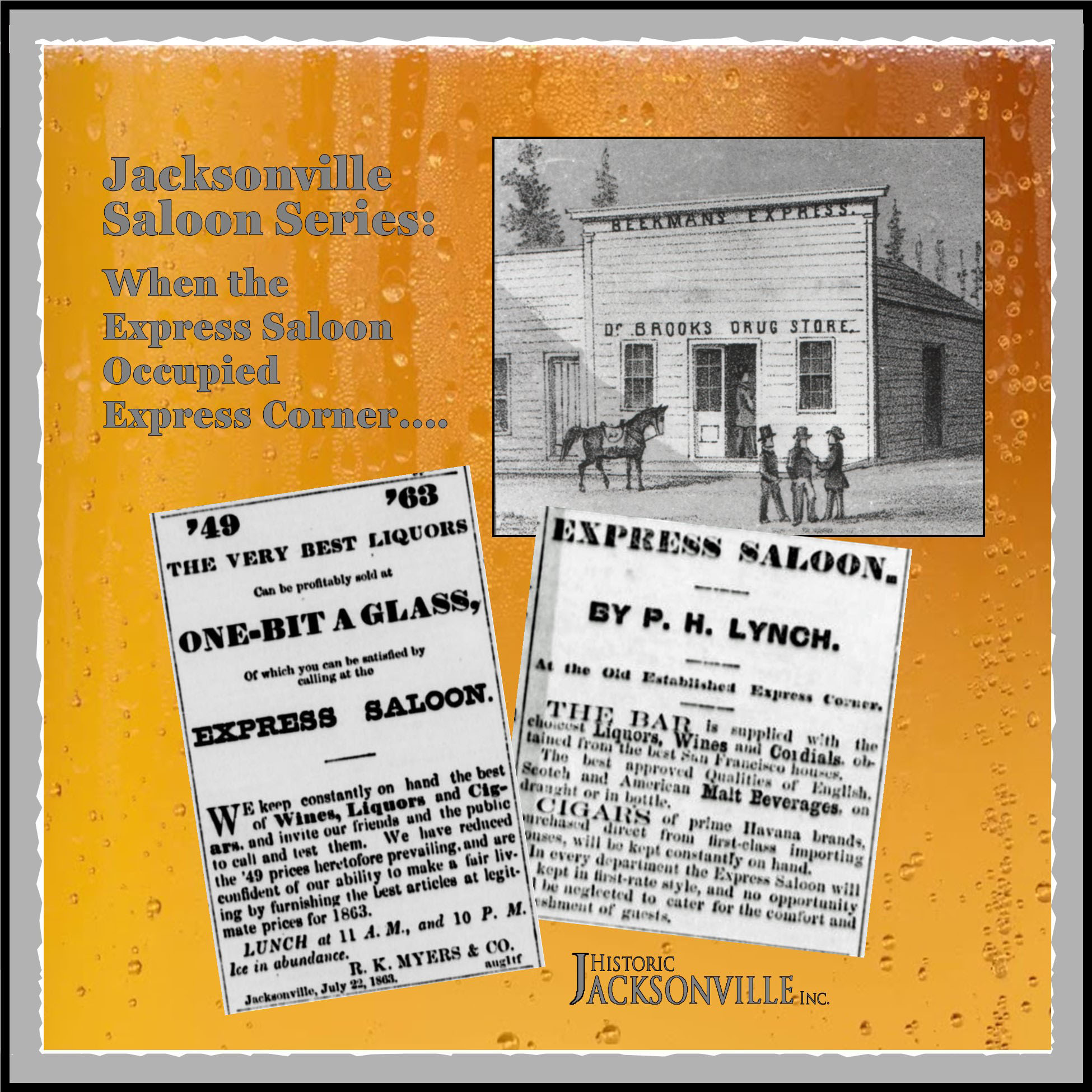

Express Saloon

When Beekman’s Express occupied the southwest corner of California and Oregon from 1856 to 1863, the location became known as “Express Corner.” So it seems appropriate that the saloon that took over the old express building was known as the Express Saloon. The Express Saloon was in operation no later than 1861 under the proprietorship of P.H. Lynch. However, according to ads in the “Oregon Sentinel,” the saloon was located “next door to Beekman’s Express Office.”

Lynch ran the saloon at least through October 1862 but is listed at year end as the proprietor of the notorious El Dorado Saloon. By 1863, Beekman had built his new banking office kitty-cornered across the street from “Express Corner” and the Express Saloon occupied Beekman’s old express building. Under the ownership of R.K. Myers & Co., the saloon advertised “the very best liquors” at 1863, not 1849, prices; “lunch” served at both 11 a.m. and 10 p.m.; and “ice in abundance.”

By 1864, John Noland is running the saloon. Although we have not located any ads for the Express Saloon after 1864, there are references to it and to “Express Saloon Corner” as late as 1866, and it appears on a hand drawn map of Jacksonville that dates to that time.

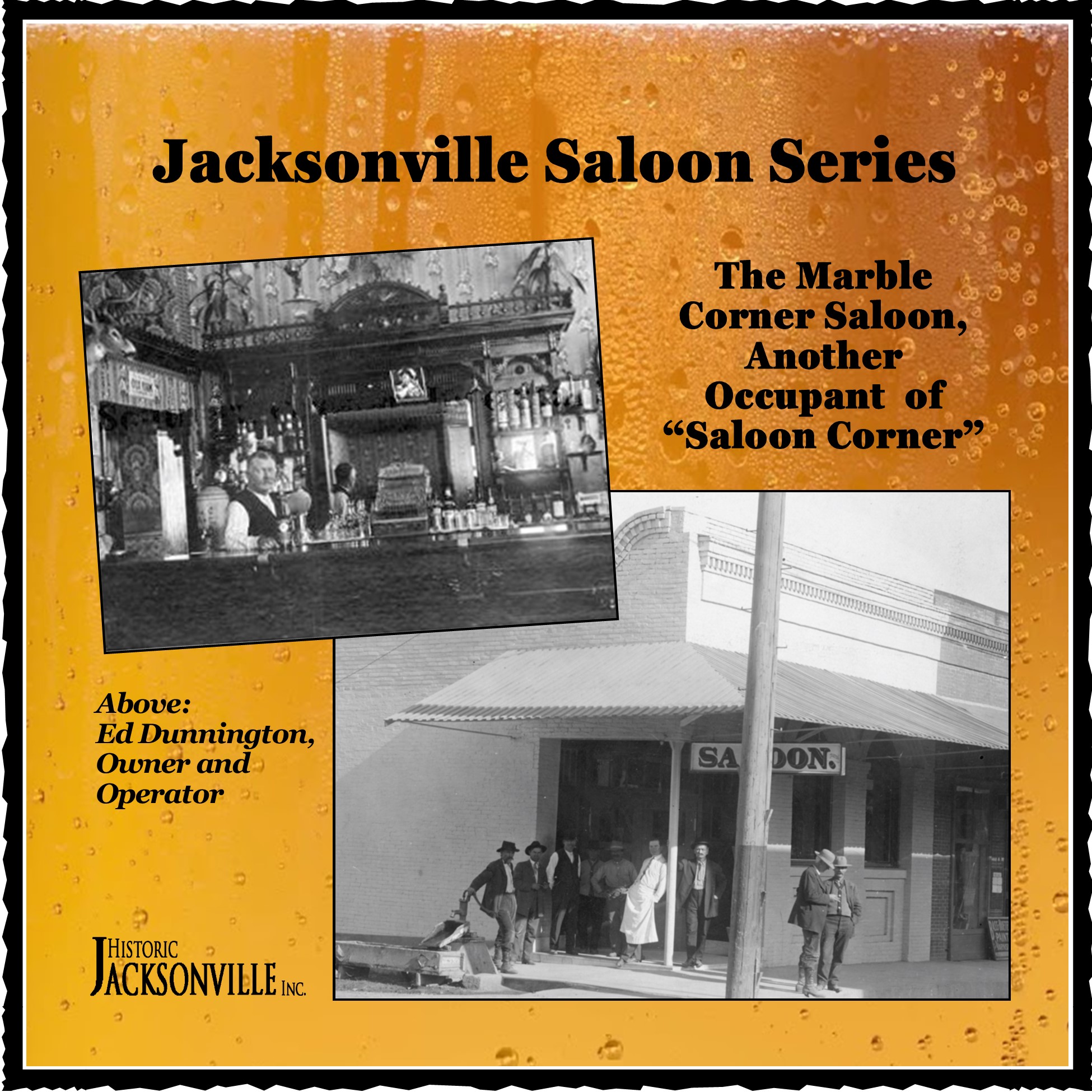

Marble Corner Saloon

We’ve already mentioned that the intersection of Oregon and California streets was a popular crossroads for early Jacksonville saloons, with the notorious El Dorado Saloon, the New England Bowling Saloon, the Eagle Brewery, the Chieftain Saloon and the New State Billiard and Drinking Saloon congregated around that location. It seems the pattern persisted with one of the longest running tenants of the 1874 brick building being home to the Marble Corner Saloon.

Also known as the Marble Arch Saloon, the saloon occupied the building from around 1890 to 1934. The saloon was presumably named after the Jacksonville Marble Works which occupied the corner directly across North Oregon after the fire of 1888…or because the saloon’s recessed entryway was tiled with marble at roughly the same time. The 1912 photo shows owner and operator, Ed Dunnington, behind the Marble Corner Saloon bar.

We’re not sure how the saloon fared after prohibition was enacted—perhaps selling sarsaparilla? After Dunnington threw in the towel, it became a confectionary known as the Chocolate Corner. That’s a far cry from the later toy store occupants!

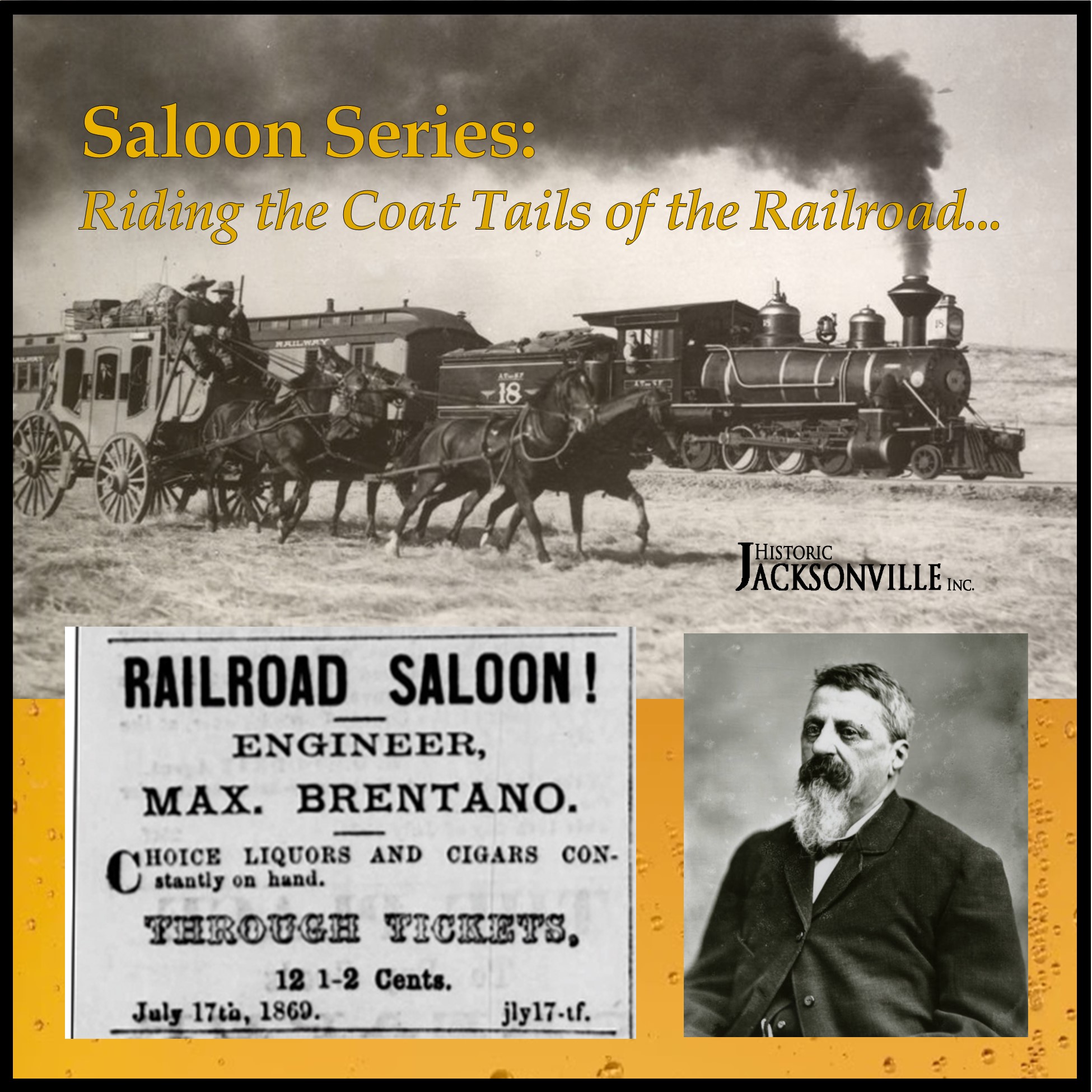

Railroad Saloon

Everyone looked forward to the coming of the railroad, knowing that it would make a big difference in their lives. In 1866, Congress had passed the Oregon & California Railroad Act which made 3,700,000 acres of land available for a company that built a railroad from Portland to San Francisco. As the railroad inched its way south, local businesses tapped into the excitement, using the railroad theme as a marketing ploy.

One such enterprising soul was Max Brentano (shown here). No later than 1869 he had opened the Railroad Saloon at the corner of California and Oregon streets, that popular Jacksonville intersection that over the years earned the designation “saloon corner.” Brentano titled himself the “engineer” and offered “through tickets” (i.e., drinks) for 12 ½ cents—even though it would be almost 2 decades before the railroad route over the Siskiyous was actually completed.

Alas, the Railroad Saloon didn’t survive to see that completion although it lasted into the early 1880s with Henry Pape as proprietor. Pape added a “reading room…well supplied with Eastern periodicals and leading papers of the Coast.” But even such “travel luxuries” did not insure its longevity. Perhaps when the railroad bypassed Jacksonville, the railroad marketing theme lost its allure…and its clientele.

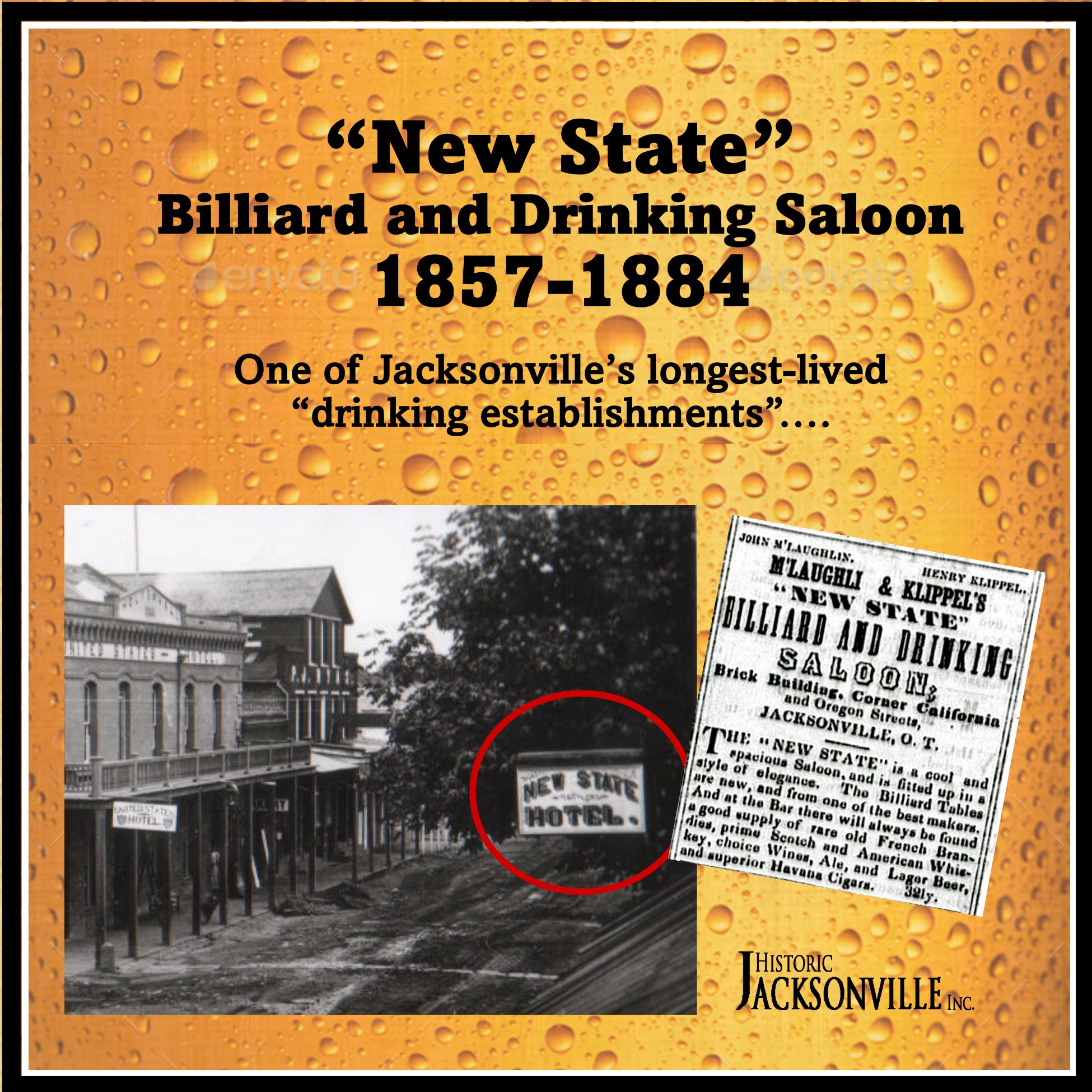

The New State Billiard and Drinking Saloon

The New State Billiard and Drinking Saloon was in operation no later than 1857 and survived until 1884, becoming one of the town’s most long-lived “drinking establishments.” It was initially owned by William McLaughlin and Henry Klippel and was one of the many saloons clustered at the intersection of California and Oregon streets. Klippel was one of Jacksonville’s prominent early residents—landowner, the first town Recorder, and an early President of the Board of Trustees.

By 1861, McLaughlin and Klippel had relocated the saloon to a 2-story brick and wooden building at the corner of California and South 3rd streets, encouraging loyal patrons to “remember the old stand” and follow them to their new location. The 2nd floor variously housed an attorney, a boot and shoemaker, and “The Oregon Sentinel” newspaper. Under the later ownership of Charles Savage, the floor became a hotel. In 1880, the newspaper reported that Savage had totally renovated the building, admiring its “improved look.”

Unfortunately, there were only 4 years for townspeople to appreciate Savage’s contribution to Jacksonville’s “new boom.” On News Year’s Day 1884, “a spiteful incendiary” started a fire that destroyed not only the New State but also much of the California Street block “despite the heroic efforts of the hook and ladder company” and a citizens’ “bucket brigade.” One month later, Savage sold the now vacant lot to the Pocahontas Tribe No. 1 of the International Order of Redmen. It’s now the site of what we know as Redmen’s Hall.

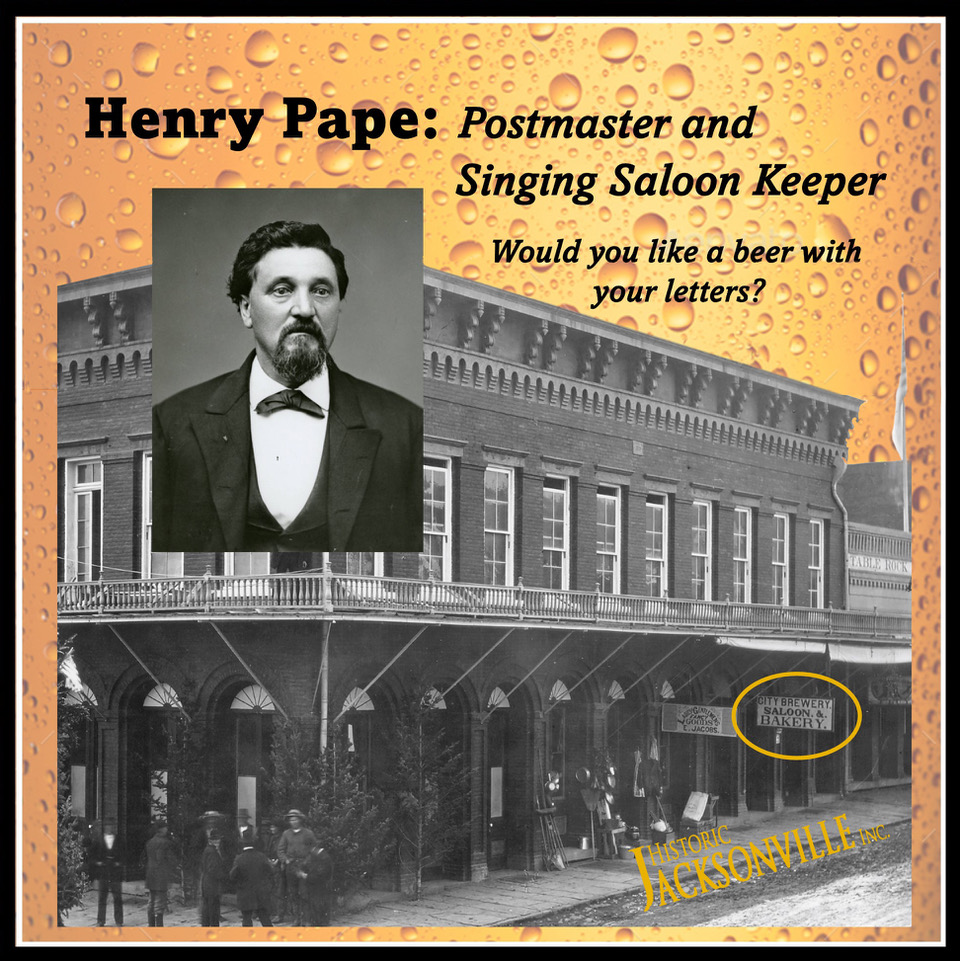

Henry Pape: Postmaster and Singing Saloon Keeper

We previously highlighted the New State Saloon, Jacksonville’s most long-lived drinking establishment in operation from 1857 to 1884. Its last owner was Charles Savage, but for almost a decade his partner was Henry Pape. However, by 1876 Pape had set up his own saloon in the new Masonic Hall building at the corner of California and Oregon, originally the site of the notorious El Dorado Saloon. In May of 1877, the “Democratic Times” noted that “Henry Pape has a snug little corner in the Masonic building and a stock of good material in fine order. He is as jolly and sings as well as ever.” We can’t attest to his singing, but Pape was also reported at various time as being “a practical mechanic,” having mining interests, as serving 2 terms as Jackson County Treasurer and several years as Jacksonville City Treasurer. In 1888 Pape was appointed Jacksonville Postmaster—and he promptly moved the post office to his saloon where it stayed for at least the 3 terms he served! Would you like a beer with your letters?

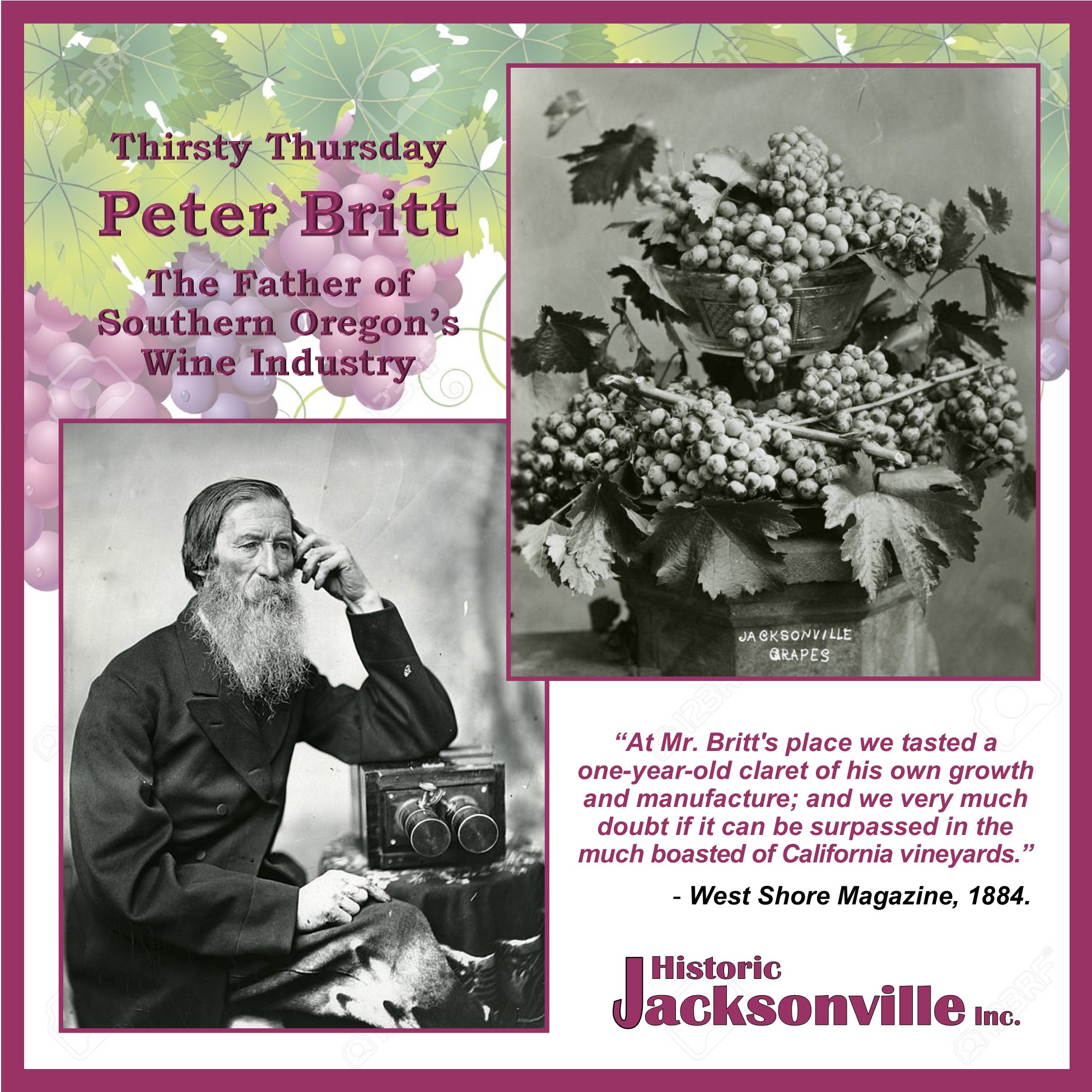

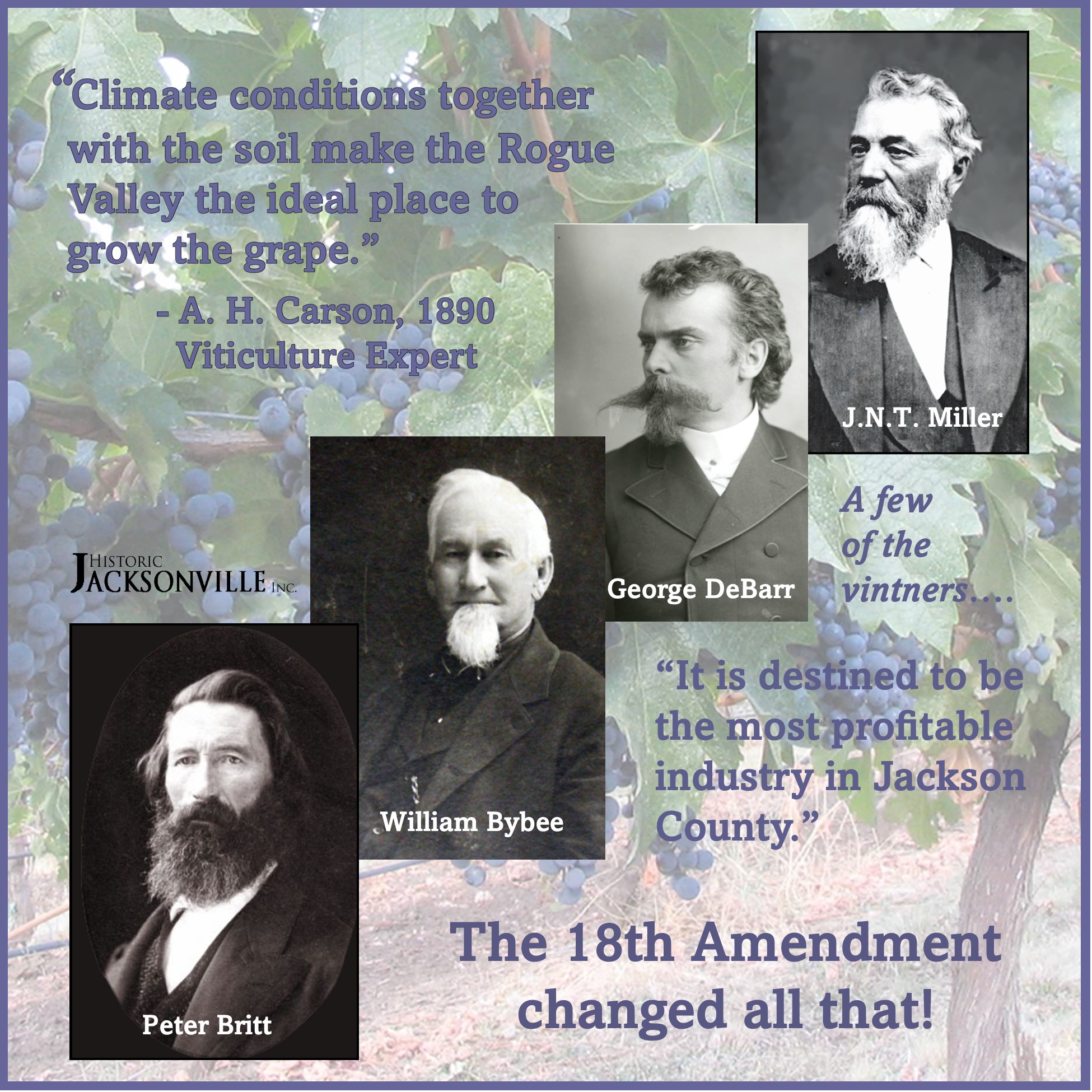

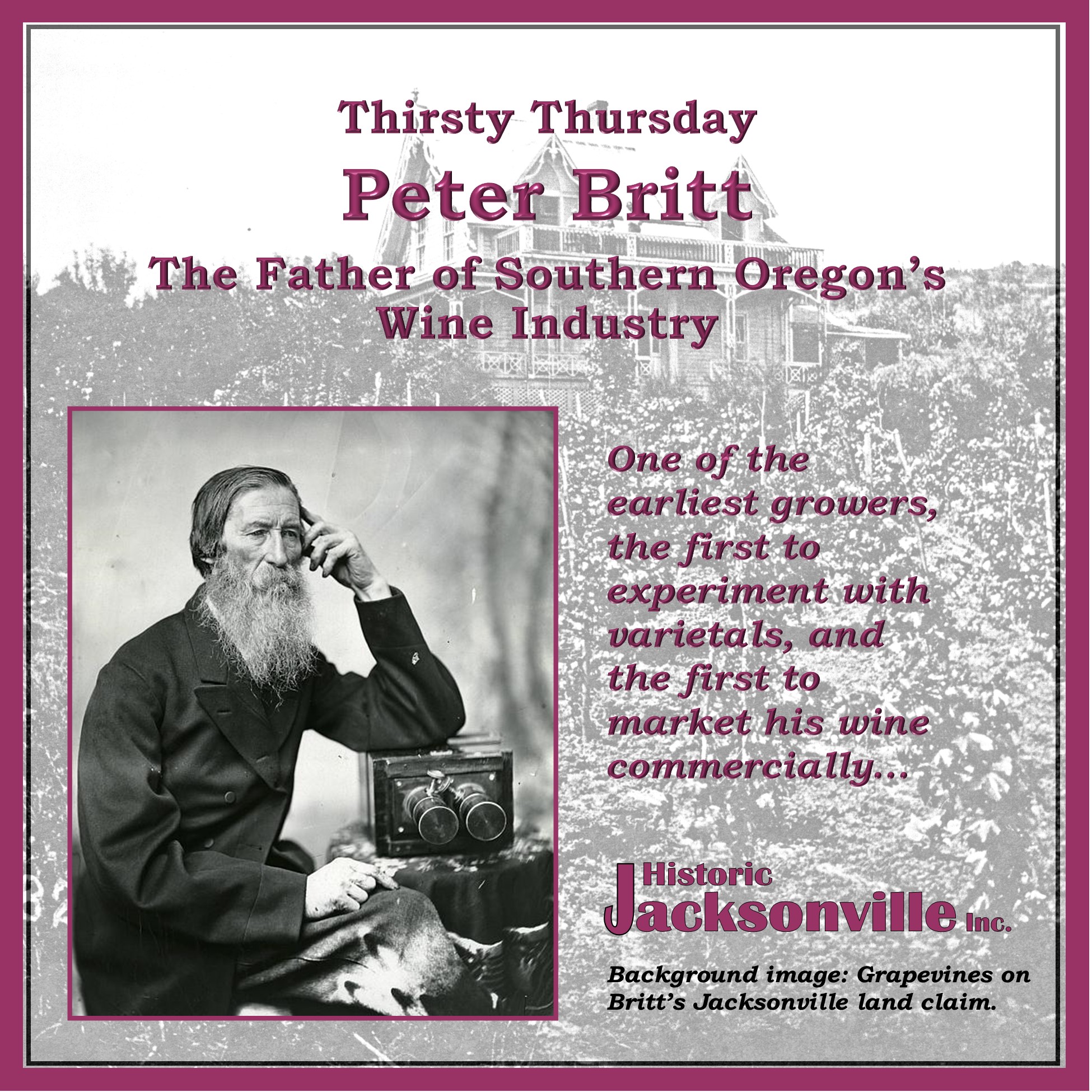

Peter Britt #1

We’ve been focusing on the saloons and neglecting the Rogue Valley’s history as a wine region. One of the earliest producers was Peter Britt. Although most of us know him as the photographer who documented early pioneer life and took the first images of Crater Lake, Britt is also considered the father of Southern Oregon viniculture. He may not have been the first to plant grape vines here, but he was the first to experiment with various varieties.

Britt had been reared in the grape districts of Switzerland, and his travels in France had added to his knowledge of the grape industry. “Noting the vigor of the wild grape vines about here, he determined to give tame grapes a trial.” By 1854 he had planted his first grape vines on his Jacksonville land claim. Family legend has it that Britt acquired his initial root stock from an Italian peddler from California. Britt’s first vines were Mission grapes, but by the 1870s he had experimented with over 200 varieties of American and European grapes, and furnished vines for almost every vineyard in the Rogue River Valley.

His records show that he made muscatel and zinfandel wines as well as a popular claret which he marketed under his Valley View Vineyard label. By 1880 he was producing 1,000 to 3,000 gallons of wine per year, eventually filling orders from as far away as Wyoming. Britt’s Valley View Winery ended with his death in 1906. The name was revived in 1972 when Frank Wisnovsky researched Britt’s earlier efforts and established one of the first commercial vineyards and wineries in the region.

In our last “Thirsty Thursday” we cited Peter Britt as one of the first individuals to plant grapevines in Southern Oregon and one of the first producers of Southern Oregon wine. However, dates are unclear. Family tradition says that in the early 1850s, having observed how well Oregon’s native grapes grew around Jacksonville, Britt secured cuttings from California mission grapevines and that by 1858 he was making the first wine in the Oregon Territory. However, the first public record of Britt’s winemaking venture comes in a September 1866 “Oregon Sentinel” newspaper: “Mr. Britt has successfully demonstrated that a first quality of wine can be manufactured here and if we may be allowed to prophesy, this will be no unimportant branch of agricultural industry in our valley ere long.”

In the 1870s, encouraged by his success, Britt expanded his operation, experimenting with dozens of grape varieties on a new vineyard one mile north of Jacksonville. As previously noted, among his more popular wines were a claret, a zinfandel, a muscatel, and a port, marketed under the Valley View Vineyard label. Apparently, Valley View was able to sell nearly all the wine it produced, in no small part due to Britt’s promotion.

He normally sold his wine for fifty cents a gallon to locals who would send over a Chinese cook or other helper with jars or bottles to be filled in Britt’s cellar. He also arranged to send bottles and larger ten-gallon demijohns of wine both north and south on the stagecoach and railroad. Britt let it be known there was a standing invitation for traveling correspondents to stop by Valley View Vineyard for a tour and a taste of wine, obviously in hope of a good review. One “West Shore” magazine writer who took the bait wrote: … at Mr. Britt’s place we tasted a one-year-old claret of his own growth and manufacture; and we very much doubt if it can be surpassed in the much boasted of California vineyards.”

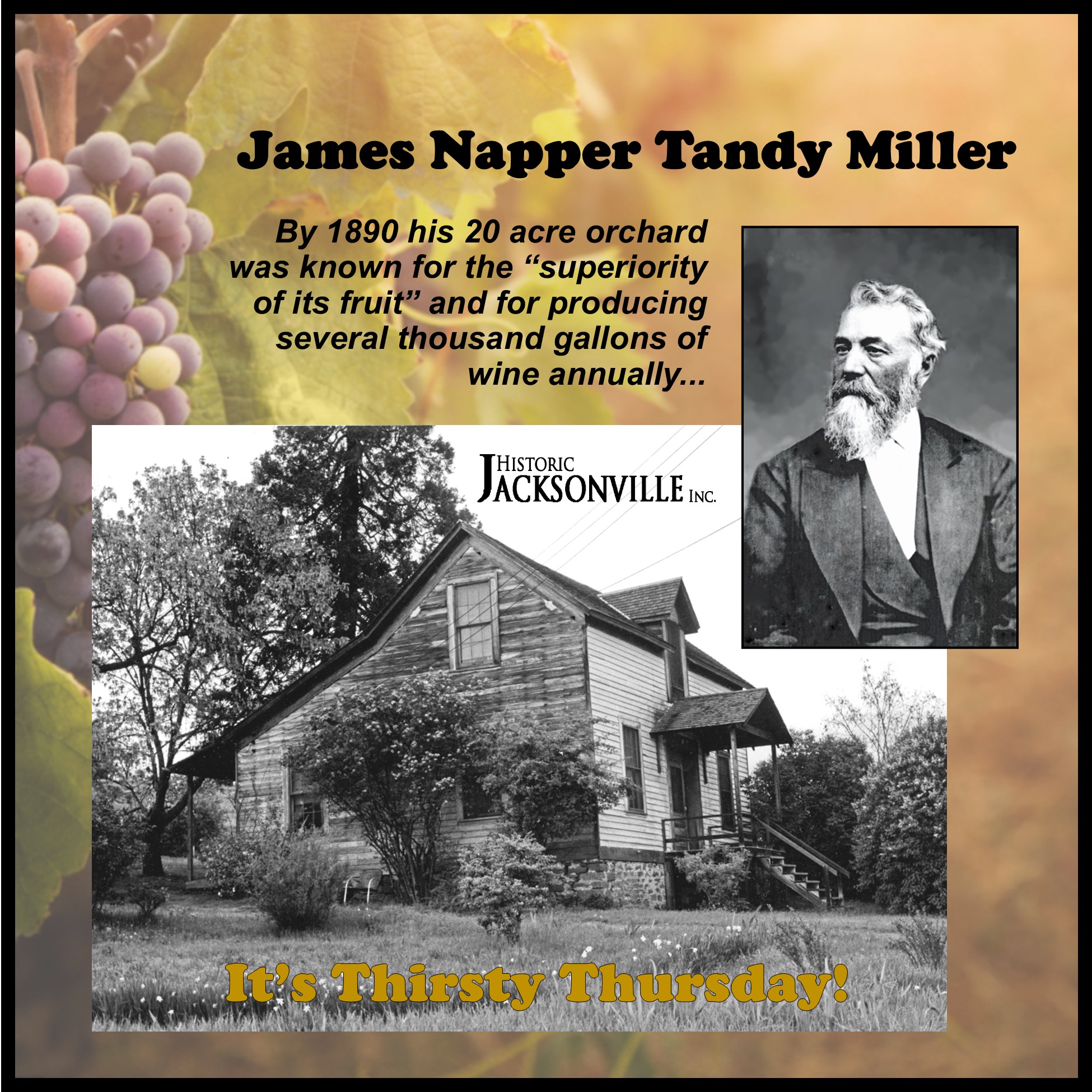

James N. T. Miller

James Napper Tandy Miller had arrived in Jacksonville in 1854 and taken out a land claim adjoining James Clugage’s claim encompassing the town’s historic core. By 1855 Miller had constructed a 1 ½ story wood frame Classical Revival style home for his family. The “Lilac House” at 401 N. Oregon Street just outside Jacksonville’s city limits, stands on the site of this earlier landmark.

Miller became a well-known figure in State politics, rising to the rank of Colonel in the Indian wars, elected a State Representative in 1862, and elected State Senator in 1866. He chaired the county’s Democratic Central Committee and began publishing the town’s “Democratic Times” newspaper.

Miller was also a farmer, grazing cattle, planting 10+ acres in orchards, and establishing one of the earliest and largest vineyards in the county —20 acres according to the 1890 State Board of Agriculture. It was known for “the superiority of its fruit,” and from it, Miller produced several thousand gallons of wine annually.

Vintners

Have you ever noticed the hops plants growing on the field at Bigham Knoll at the east end of E Street? The German-speaking immigrants who contributed so much to early Jacksonville culture also brought with them their recipes for German lager with its pronounced flavors of malt and hops. Initially, these early brewmeisters would have grown their own hops, a flowering vine that is trained to grow on tall strings strung between posts.

Really tall strings. So tall, in fact, that before the advent of hop harvesting machinery, farm workers had to use stilts to tend the plants. Harvesting hops were so labor intensive before mechanical harvesters were invented that entire families of migrant farm workers took part in the harvesting process, taking advantage of the plentiful work and employment opportunities.

Prohibition

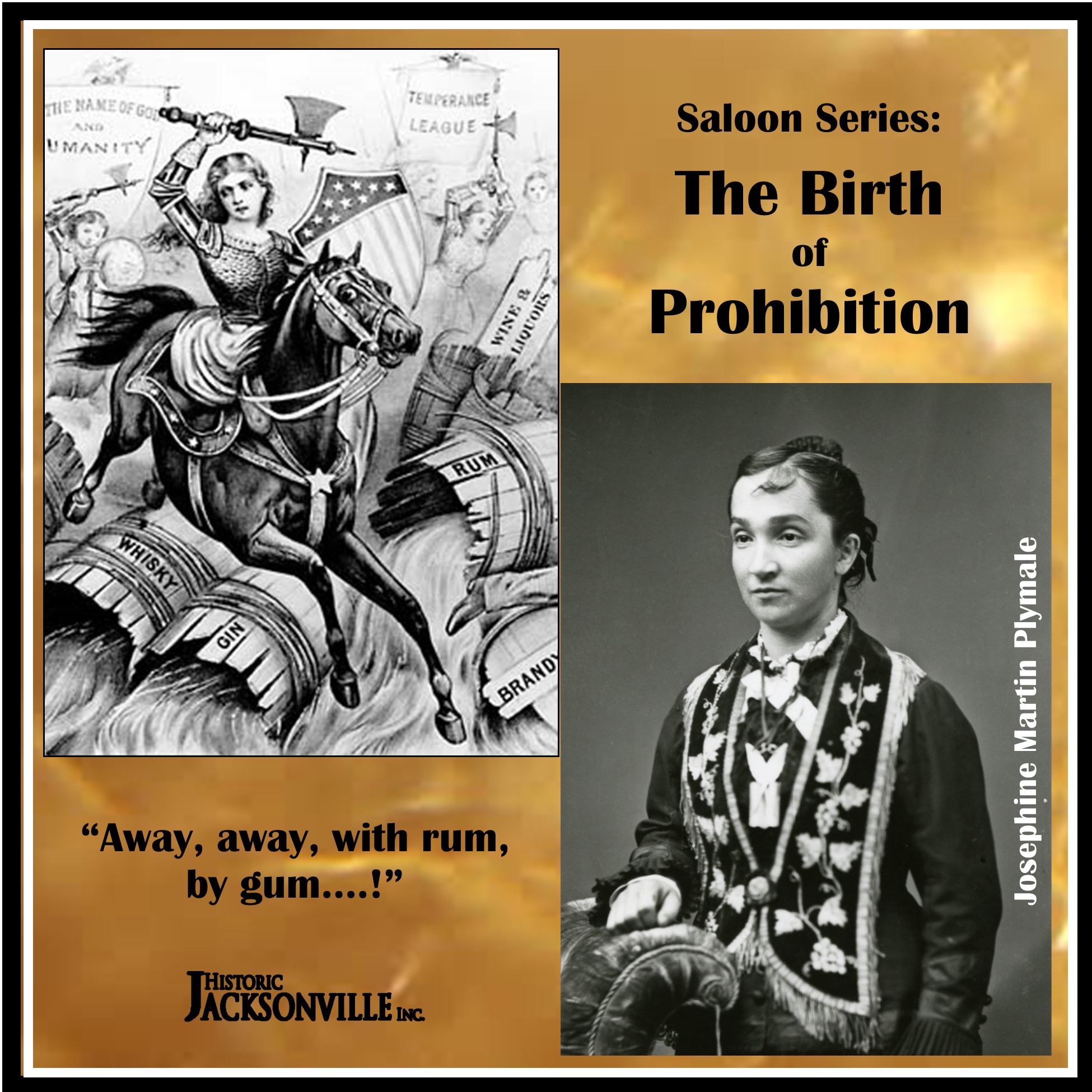

Sir Isaac Newton said, “To every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.” At about the same time Peter Britt was planting what would be Oregon’s first commercial vineyard, the movement that ultimately resulted in Prohibition was being born.

But before Prohibition became a law enforcement issue, it was a moral and political issue that dated back to the earliest days of Oregon’s settlement. The Oregon version had its roots in the Oregon Temperance Society, formed in 1836 by Methodist missionaries who had arrived in the Willamette Valley only 2 years before. They brought with them powerful sentiments about alcohol that were held by a growing number of citizens throughout the country.

The movement blossomed after the Civil War. National organizations such as the Anti-Saloon League and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) set up branches in Oregon and gained enormous political power. National leaders formed a new political party, the Prohibition Party. Though prohibition was the party’s central plank, leaders also argued for direct election of senators, a graduated income tax, and women’s suffrage.

Women’s suffrage both brought women into the party and reflected their influence in the party. One such suffragette was Jacksonville’s Josephine Martin Plymale. She was Vice President of the Oregon State Women’s Suffrage Association, described as “one of the most active workers in the Women Suffrage field…anywhere.” She was also treasurer of the Jacksonville branch of the WCTU. The combination did not sit well with men who liked their alcohol. And, ironically, her husband, William Plymale, had at one time been licensed to sell liquor!

Petards and Prohibition

Early settlers recognized the Rogue Valley’s potential for grape and wine production as early as the 1850s. French-born Auguste Petard was a Johnny-come-lately to the scene, arriving around 1900. Initially in search of gold, there was also land to be had—ideal for vineyards and winemaking, something he knew well from his native France. His wife and sons joined him, and he purchased the hillside acreage next to the stream where Jacksonville gold was first discovered.

By 1918, the Petards had planted 20 acres of grapevines on the slopes and produced a little red and white vin ordinaire. Life was good. But there was this strange English word, “prohibition.” Then in 1919, there was this Volstead Act.

Rumors of the Petard’s “illegal wine” reached the members of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. They demanded the Sheriff act. Armed with a search warrant, he discovered at least 600 gallons plus 50 quarts of wine. Local ministers and 16 members of the W.C.T.U. gathered to watch the sheriff’s deputies bash the barrels with their axes and dump the wine on “schoolhouse hill.” In 1922, $4,000 of Auguste’s wine soaked into the weeds of Bigham Knoll….

Prohibition Moves On

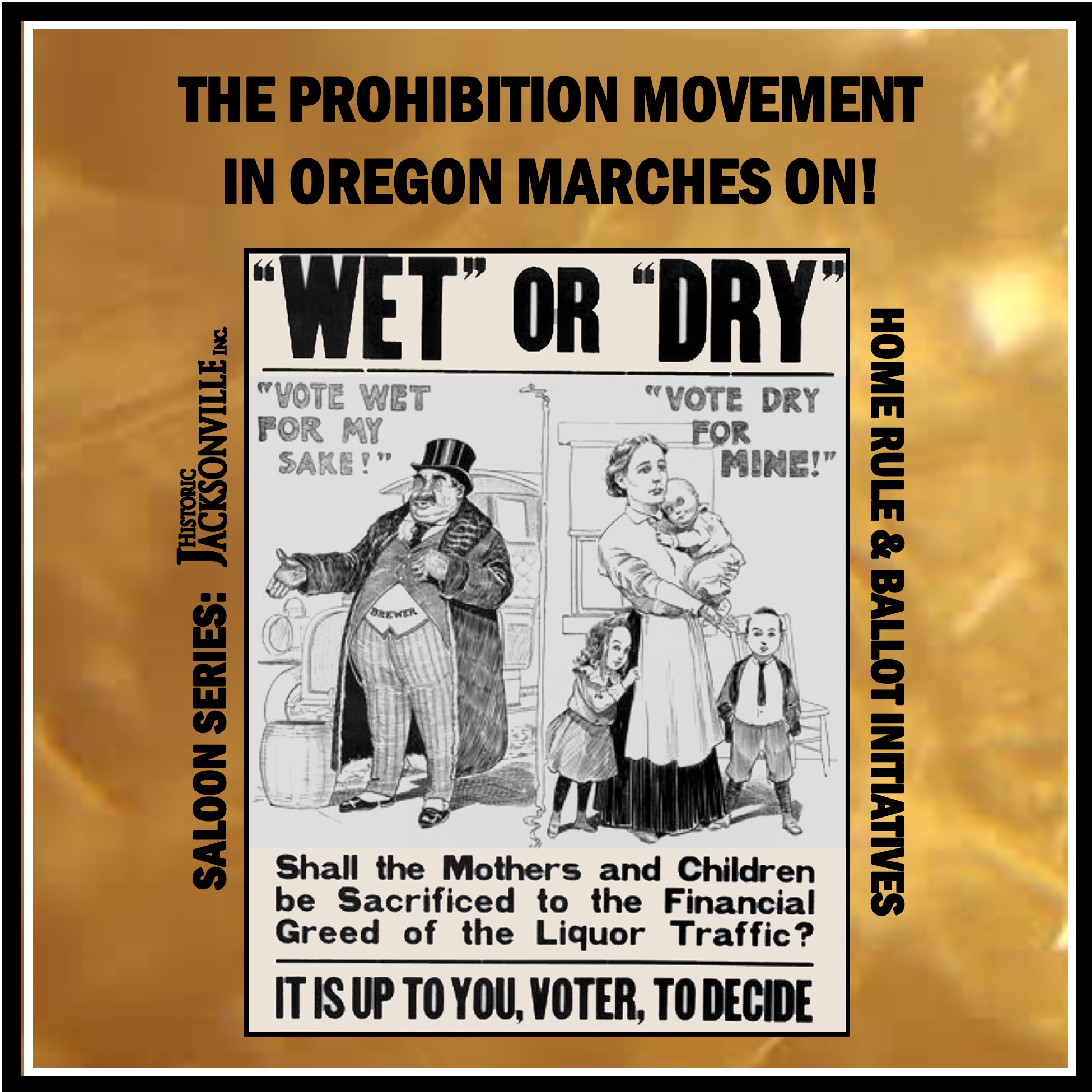

When the national Prohibition Party was formed after the Civil War, its pro-women’s suffrage plank attracted many women members.

Attempts to legislate prohibition grew, all failing until 1904. Oregon’s new initiative laws enabled prohibitionists to place local ballot measures called “local option laws,” that called for the prohibition of alcohol in local political divisions as small as precincts. If the division voted “dry,” the division went dry, even though a neighboring division might stay “wet.” Prohibition became an issue of local political autonomy as well as a moral issue.

Jackson County stayed dry, in part due to liquor interests controlling the state Legislature. But in 1910, the “home rule” amendment to the state Constitution gave cities the ability to write their own charters—which could include references to liquor. Some population centers became wet oases in the middle of dry deserts and vice versa.

The prohibition juggernaut soon mowed down all opposition. After Oregon women gained voting rights in 1912, Oregon again took up the issue of prohibition in a statewide ballot initiative. Thirty-two of the state’s 34 counties voted for “prohibition.” On January 1, 1916, Oregon went dry. Nine hundred saloons and 18 breweries in 98 towns closed….

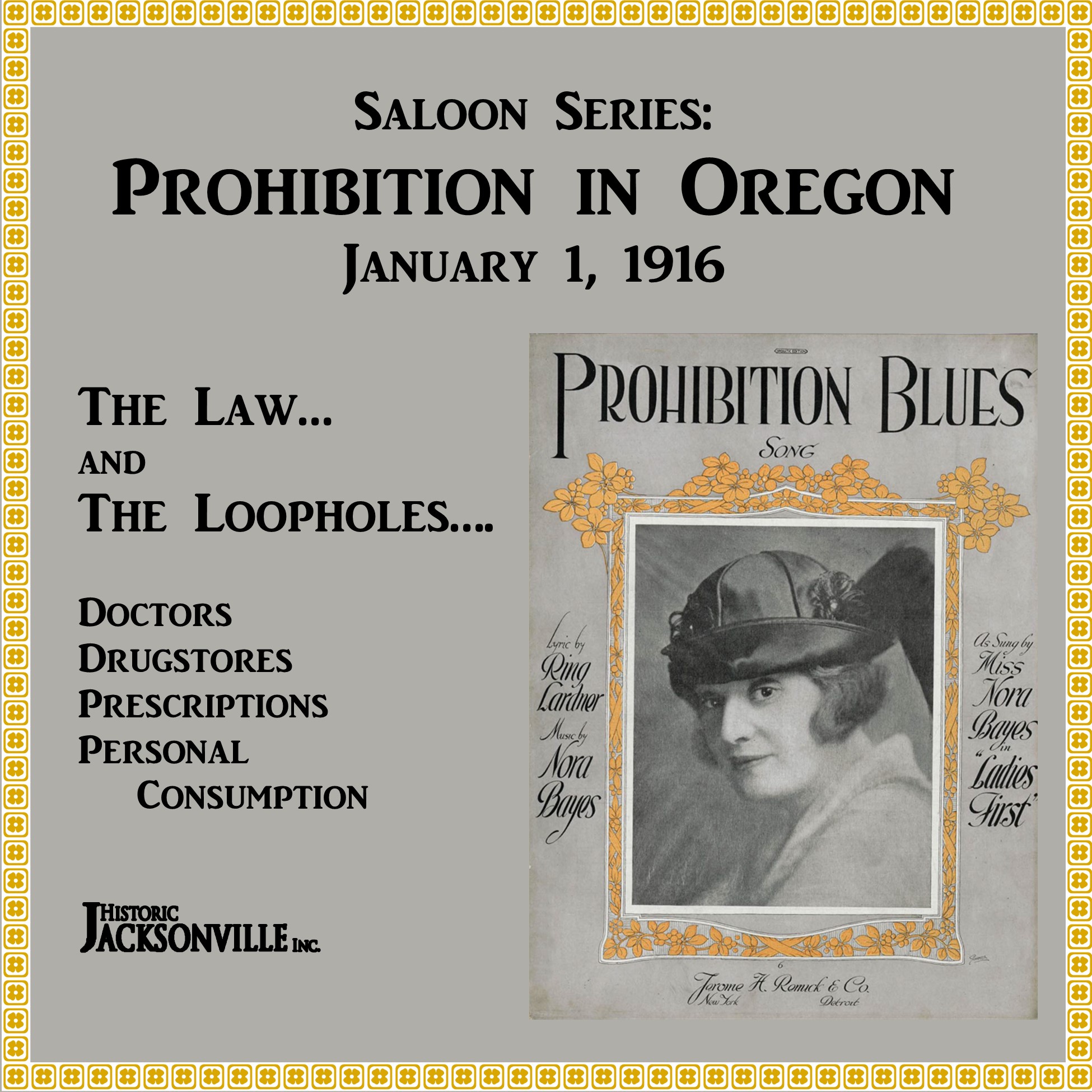

Prohibition – the Law and Loopholes

Oregon went dry on January 1, 1916, when a statewide ban on alcohol took effect—but that didn’t mean that you couldn’t get a drink! The Oregon Enforcement Act banned all the usual kinds of liquor and defined the places and vehicles where liquor was manufactured, sold, or given away as “common nuisances.” The act forbade businessmen from taking liquor orders. Printers could not print or distribute ads for liquor. Giving liquor away with intent to evade the law was forbidden. No one could carry liquor into a dance hall.

But like many laws, the Oregon Enforcement Act had a few loopholes. Doctors were permitted to prescribe and drugstores to carry it for sale by prescription. And a person could bring up to 5 gallons of wine or spirits and up to 20 gallons of beer per month into the state.

However, the primary effect of early prohibition in Oregon seems to have been to enable bootleggers to get in some practice before the federal government got involved and consequences became serious. When the Volstead Act passed in 1919, inaugurating nationwide Prohibition, Oregon’s entrepreneurs were ready to go!

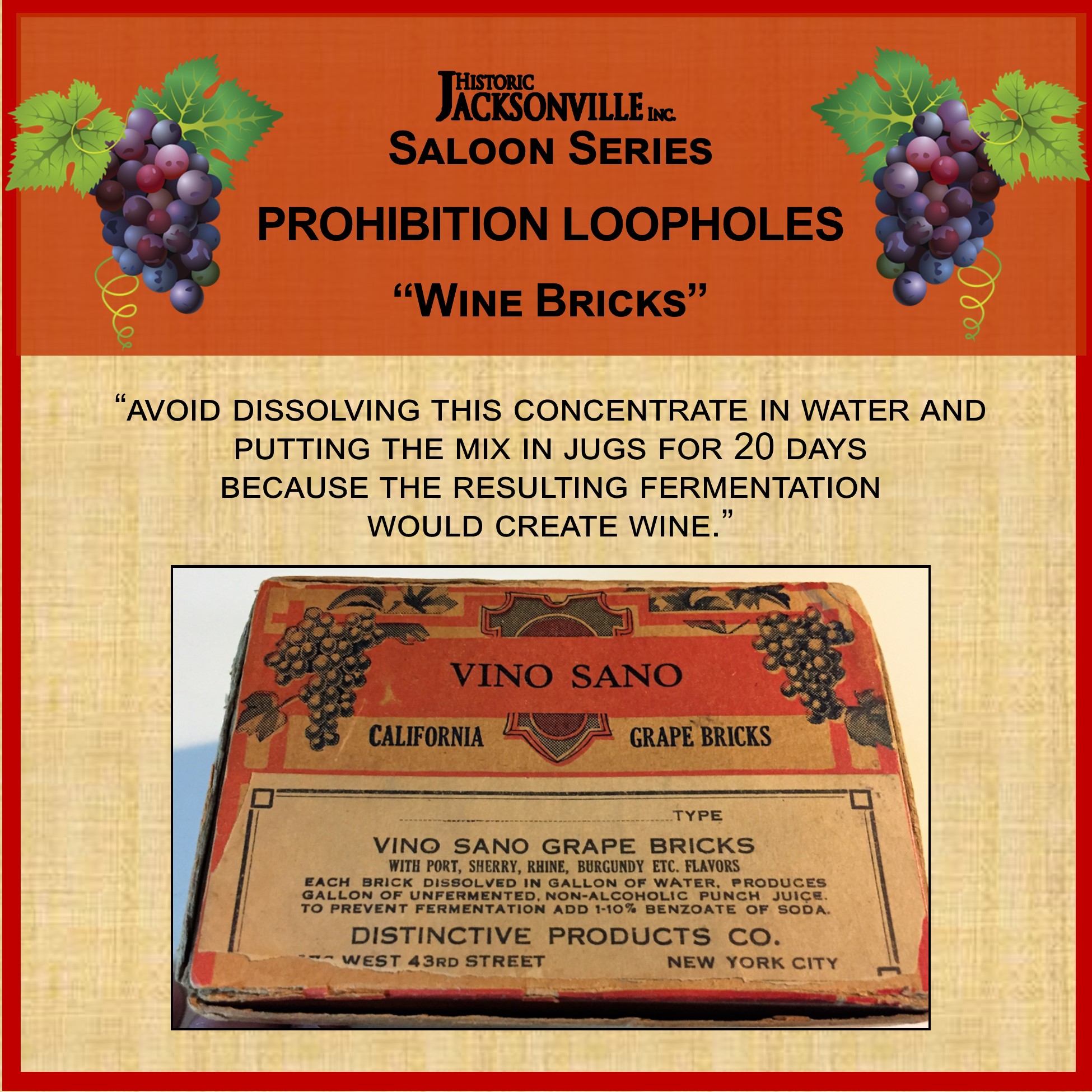

Prohibition – Wine Bricks

In 1916, when Oregon preceded the rest of the nation into the era of Prohibition, the local market for wine, so promising at the turn of the century, disappeared nearly overnight. The only markets for grapes that remained by 1920 were for table grapes, not the varietals so carefully developed for fine wines. After the passage of national Prohibition—the Volstead Act—on January 17, 1920, acres and acres of Oregon’s grapevines were uprooted or allowed to run rampant, effectively destroying them.

However, the new law did not specifically prohibit the consumption of intoxicating liquors, defined as more than 0.5% alcohol by volume. Human nature being what it is, people stocked up on their favorite alcoholic beverages in the period leading up to enforcement of the Act. Others took advantage of a provision allowing up to 200 gallons of “non-intoxicating cider and fruit juice” to be made each year at home. Home vintners flourished, using elderberries, local fruits, and wild grapes to make their own concoctions. People rapidly discovered that it was easy to make wine.

While Oregon’s wine industry died, many California vineyards and wineries stayed afloat and maintained their vineyards by producing grape juice and grape juice concentrate. Customers soon realized they could legally purchase the grape juice or concentrate and ferment it themselves into a drinkable wine. Wineries began selling blocks of grape concentrate known as “wine bricks.” Instructions admonished people to avoid dissolving the concentrate in water and putting the mix in jugs for 20 days because the resulting fermentation would create wine. But again, human nature being what it is….

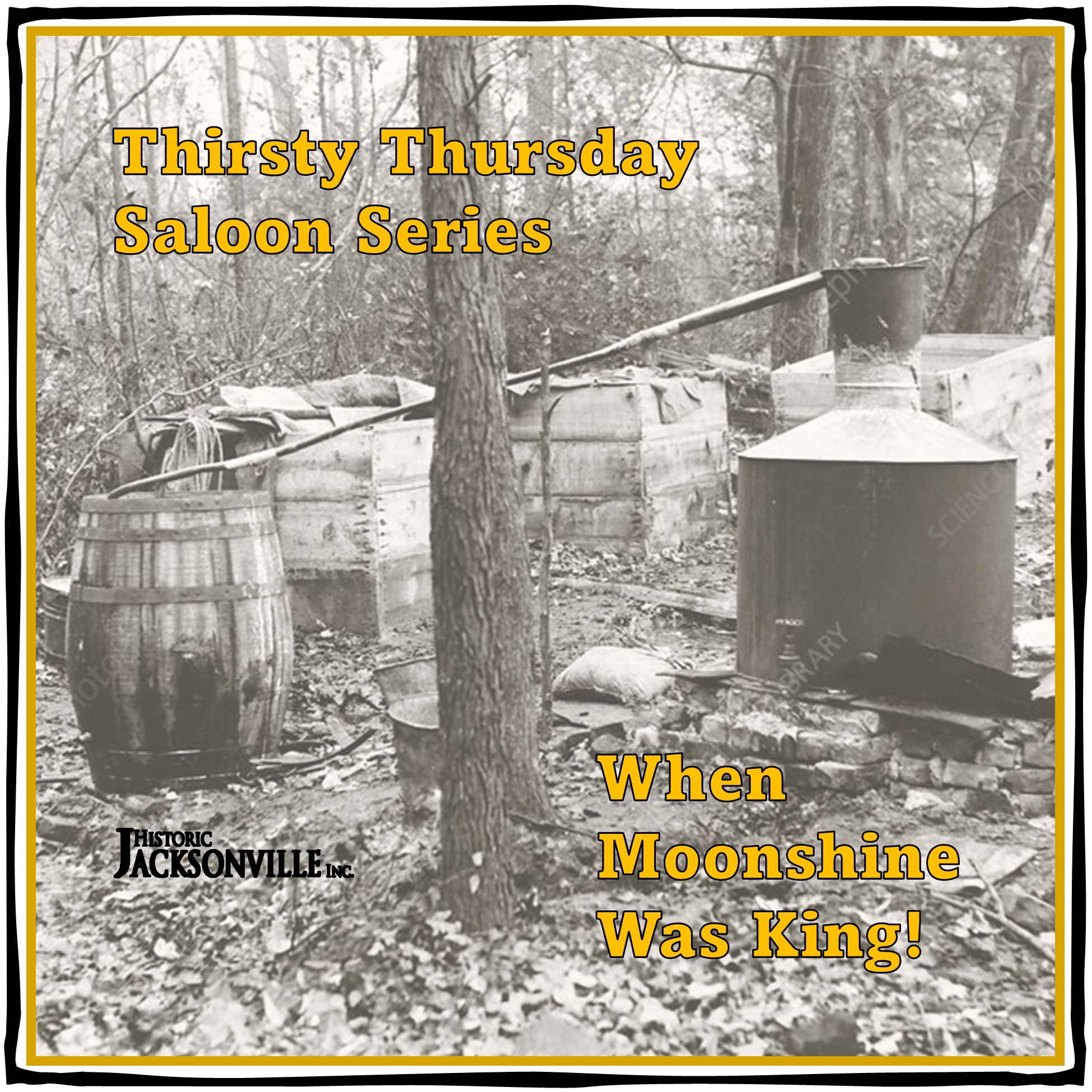

Prohibition – Moonshine

With the passage of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution in 1919, the United States went “dry.” But “John Barleycorn” was not dead! He had certainly not died when Oregon went “dry” in 1916. Citizens who enjoyed his intoxicating brews had found ways to obtain them in the years before nationwide prohibition. Historic Jacksonville, Inc. has already noted how rapidly people turned to home brewed wine. “Hard liquor” was close behind, and following the Volstead Act, stills proliferated. One Jackson County deputy sheriff cited “stills in every section of the county.”

Local residents perfected the art of making moonshine. Even children were entrusted with part of the process. Many moonshiners remember their product as “superior to that sold in bottles.” Here’s one recipe for “Moon”:

- 500 to 600 pounds of rye

- 500 to 600 pounds of sugar

- 30 to 40 cakes of yeast

- 10 to 12 fifty-gallon barrels with spigots at the bottom

- A reliable still

Dissolve 50 pounds of sugar in lukewarm water. Add three to four cakes of yeast. Pour 50 pounds of rye into one barrel. Add sugar and yeast mixture. Repeat for all barrels. Mix well and let stand six to seven days. Three to four inches of foam will form on top of mixture. Skim off. Mash is now ready to run. Place a bucket under the spigot and drain out the liquid. Each barrel will have about 25 gallons; one barrel to a still. Seal the still and fire up. Bring the liquid to a boil. Steam will now flow through the copper tubing through the condenser filled with cold water. Collect product in jugs. Each mash may be used up to four times.

Yield: 125 gallons of 70 to 75 proof

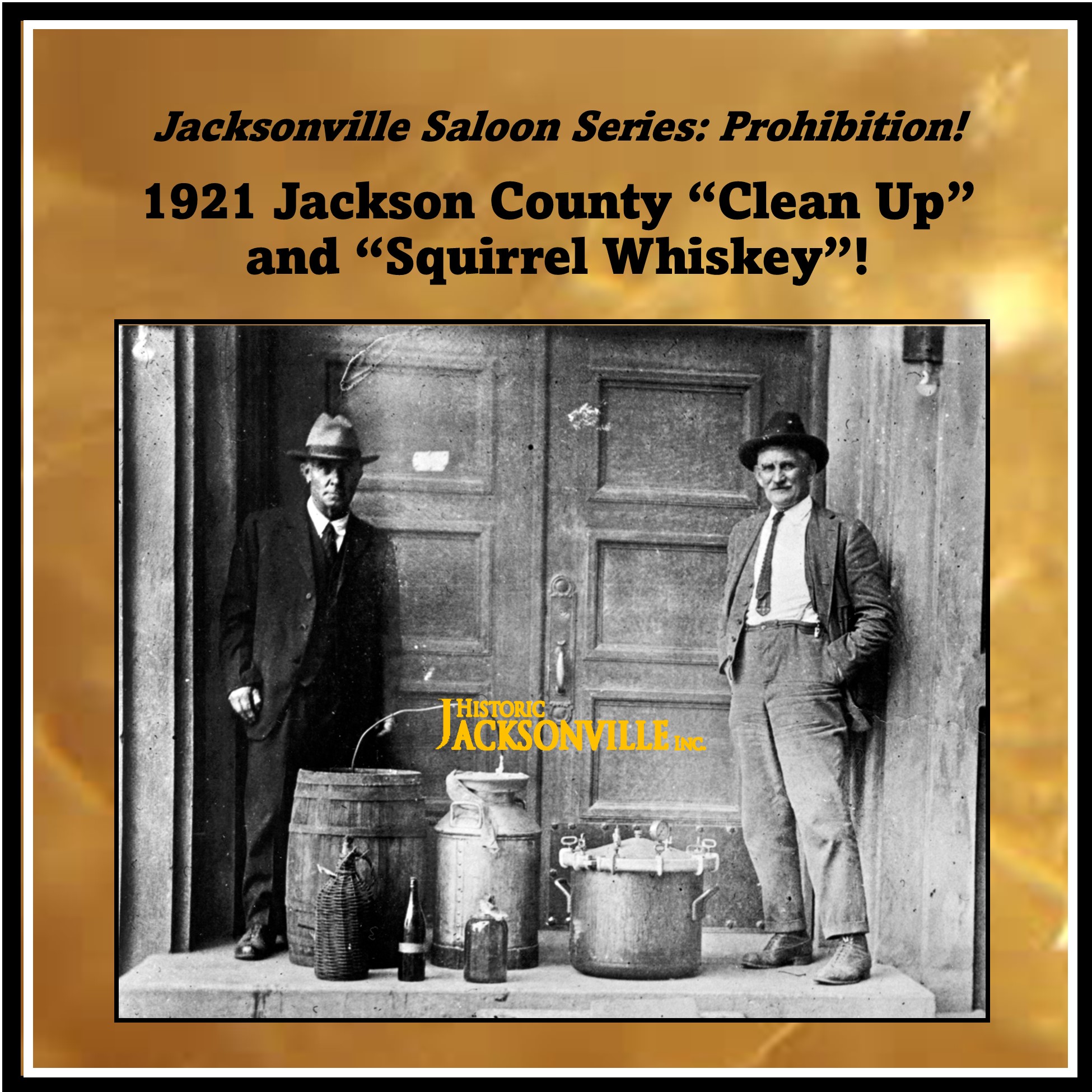

Prohibition – Squirrel Whisky

With Prohibition in full effect, local officials went into a “county-wide cleanup of suspected bootleggers and illicit stills” in 1921. Officers went on the hunt for “stills and booze peddlers.” On August 18th the Mail Tribune reported the seizure of 3 stills in the “Jacksonville Hill District,” aka “Rich Gulch,” with 2 men arrested for engaging in whiskey traffic.

J.M. Rock, a farmer, pleaded guilty to having a half gallon demijohn in his possession. Upon the plea that he was the father of five children and a new arrival was expected any day, he was allowed to go on his own recognizance until trial.

Ike Coffman, a homesteader, was charged with having in his possession “a mixture of figs, prunes, and water in the process of fermentation.” According to arresting officers, Coffman’s still was an “emergency supply” for local moonshiners. His mash was kept in a tin boiler in a deserted shack. Dead gray squirrels and bats were found around the still, the animals having dropped from the rafters into the brew, and cooked alive. Although these “seasonings” might have provided a “flavorful” brew, they might also have insured any partaker of the concoction either major diarrhea or instant death!

Arresting officer Sheriff Charlie Terrell is shown right in this photo in front of the then Jackson County Jail, now Art Presence.

Prohibition – Bootleggers vs. Moonshiners

For those seeking “refreshment” during Prohibition, the bootlegger became their hero. The bootlegger was the one who transported the moonshine and other illegal liquors. Unlike the moonshiner or the drinker, the bootlegger risked capture on the road and sometimes even his life. But a bootlegger could make as much as $500 trip (equal to over $8,000 today). One report has a bootlegger selling 10 gallons of moonshine for $800—think almost $13,000!

According to one source, the bootlegger usually drove a “flashy” car—a red Studebaker or a black Packard. If he drove a team, it was a large team that hauled 2 wagons. In contrast, most took great caution in selling their product. They would only give instructions on where to find a purchase after money changed hands. For example, “Go down to the fence corner, count so many posts, and you’ll find a pint in there.” That way the law couldn’t tie the bootlegger into the deal. The only thing they could do was catch the guy with the liquor and pour it out in from of him, who would most likely stand there “with his mouth waterin’.”

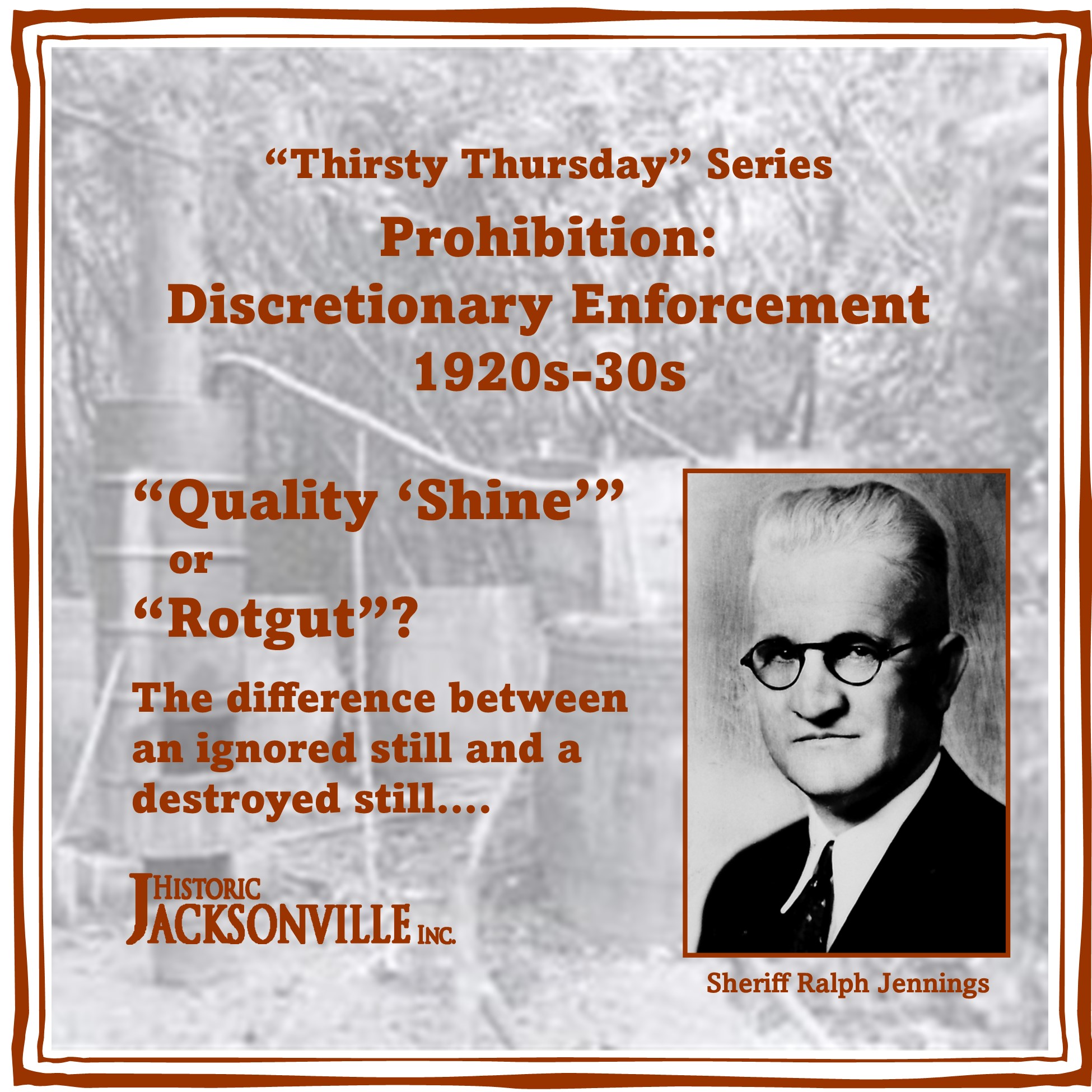

Prohibition – Discretionary Enforcement 1920s – 30’s

During Prohibition, enforcement of the laws could be a hit or miss proposition. But sometimes the law also chose to turn a blind eye. During the 1920s and early 30s, Jackson County Sheriff Ralph Jennings spent much of his energy fighting the liquor trade—but apparently, he did so with discretion. One “old timer” claimed that Jennings would leave a moonshiner alone as long as he produced a good product and didn’t sell it to children—which may have contributed to Jennings being a well-liked sheriff.

According to a 1977 oral interview with Ellis Beeson, “There wasn’t anything that went on in the county that [Jennings] didn’t know about. If some fellow fired up a still some place, and Ralph heard about it—which probably would be within a couple of days–why, he’d send one of his men to get a sample of the moonshine. If it was good moon, he would be left alone. But if he was making rotten moon, they just destroyed the still and told him to get out of business.”

It’s claimed that some of the moonshine made at the time was “superior to that now sold in bottles,” which could account for law enforcement’s selectivity. Of course, “good quality” was also defined by some as “liquor that could be drunk without poisoning you.” In fact, the term “rotgut” came from liquor that did poison, essentially, rotting your gut….

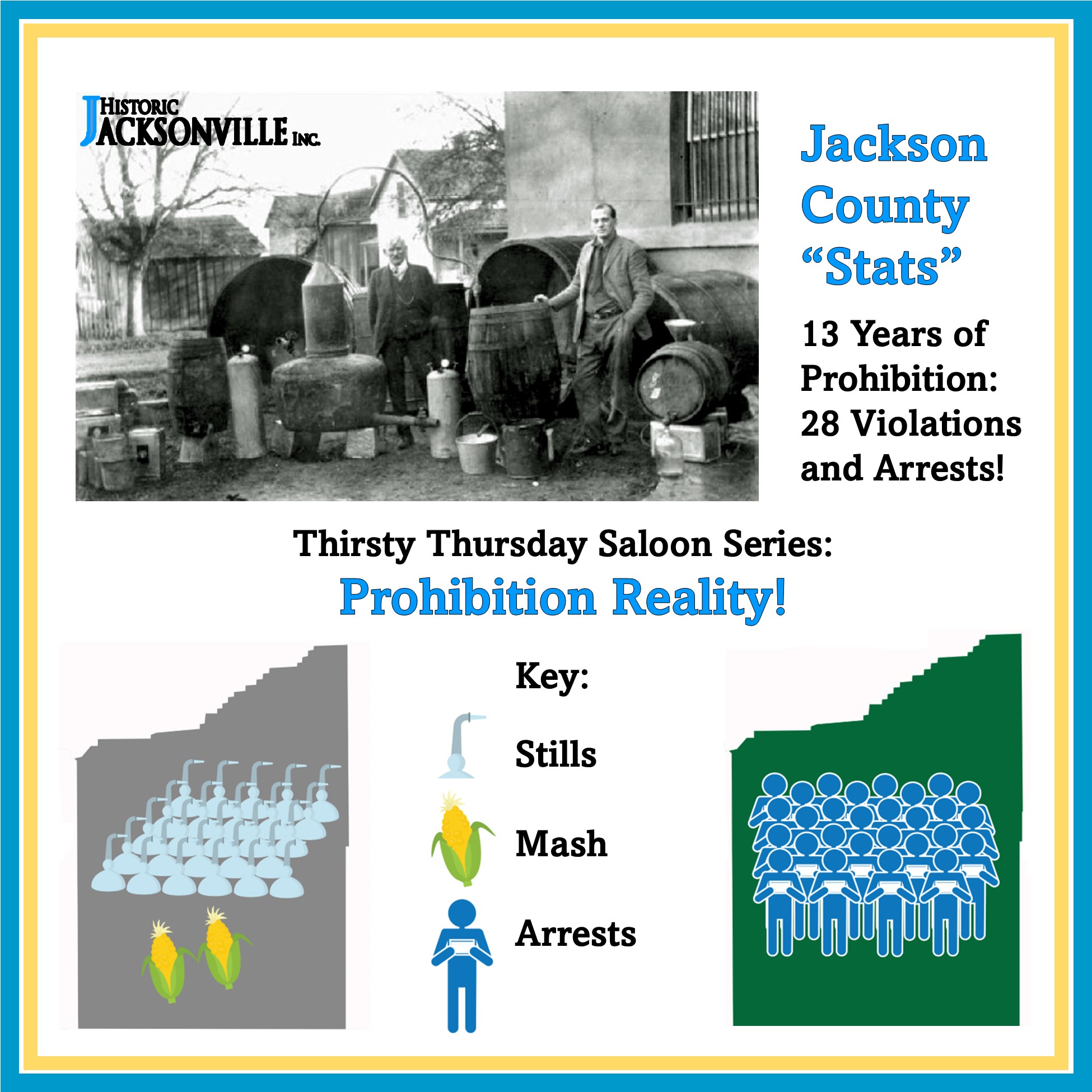

Prohibition – Jackson County “Stats”

We’ve already noted that during Prohibition, enforcement of the laws could be a hit or miss proposition depending on whether lawmen could catch the perpetrators and on how zealously the law was enforced. Despite moonshining and bootlegging stills and arrests making regular newspaper headlines during the 13 years that the Volstead Act was the law of the land and Prohibition “enforced,” official Oregon reports show only 28 Jackson County violations and arrests on record! Historic Jacksonville, Inc. is not sure whether that means that Jackson County was a bastion of virtue, local information was selectively reported to the state, or that local law enforcement was inclined to turn a blind eye. Could it have been all 3?

We do know that a Vaudeville act appearing at one of the Medford theaters during this period included a sketch where a drunkard was asked, “Haven’t you had heard of Prohibition?” The supposed reply was, “No, I’m from Jacksonville.”

What’s New: Prohibition – Presidential Politics

By the late 1920s, Prohibition as a political, moral, legal, and law enforcement movement was dying. However, Prohibition’s proponents still held the “high ground,” at least where politics was concerned. That’s why in 1929, when Franklin D. Roosevelt announced his candidacy for U.S. President, “dries and prohibitionists” were sharply threatened by the fear that, once elected, he would repeal the Eighteenth Amendment. Some of them thought as long as liquor was illegal their town would be safe. A 1931 Medford postcard boasted: “Our town–bright, progressive and sober, but sober. Come on up and see it before the 20th Century ruins the local color.”

However, the “dries’ and prohibitionists’” fears were realized. Roosevelt was elected, and in 1933, the nation went “wet” when the 18th Amendment was repealed. Oregon established its own Liquor Control Commission and took over the sale and distribution of strong liquor by the bottle. The business of liquor, outside of manufacturing, was no longer a private concern. However, in Oregon—and Jackson County—local option laws still prevailed….

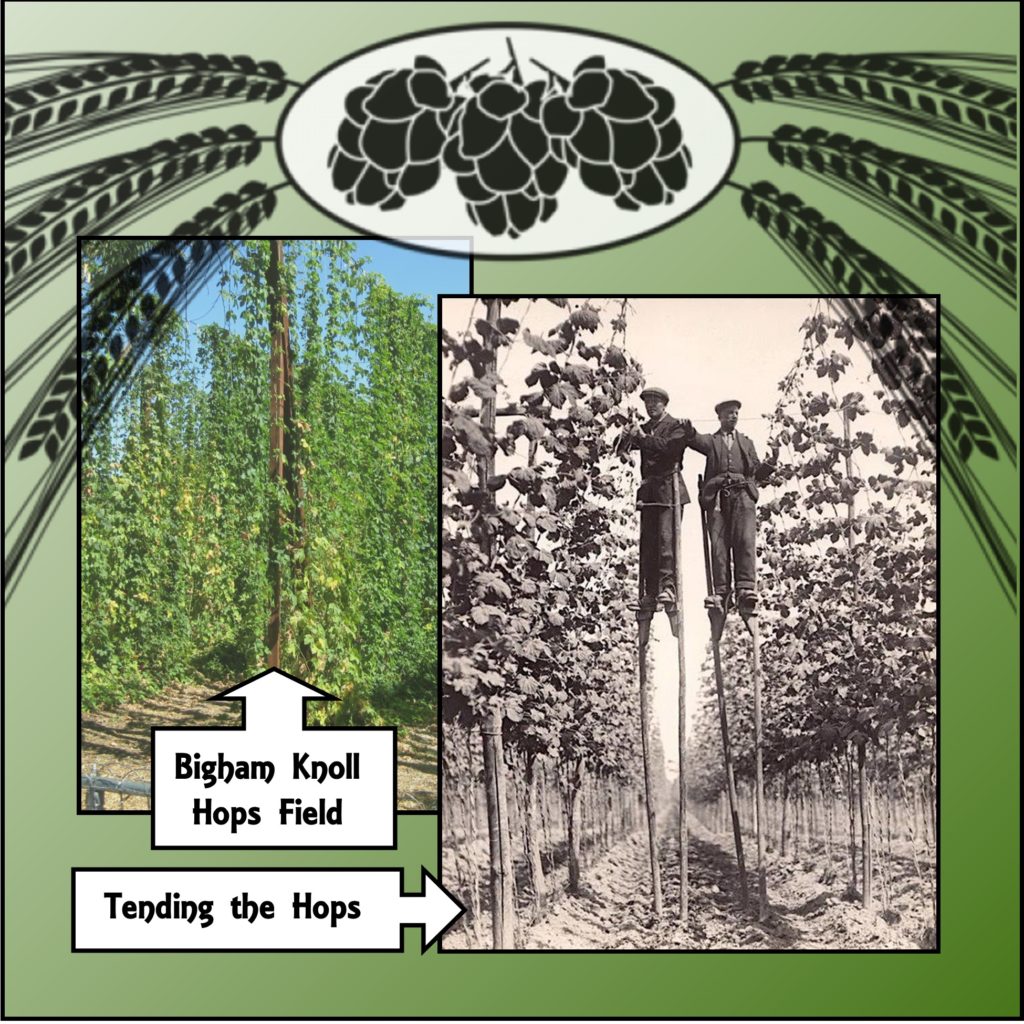

Tending the Hops

Have you ever noticed the hops plants growing on the field at Bigham Knoll at the east end of E Street? The German-speaking immigrants who contributed so much to early Jacksonville culture also brought with them their recipes for German lager with its pronounced flavors of malt and hops. Initially, these early brewmeisters would have grown their own hops, a flowering vine that is trained to grow on tall strings strung between posts.

Really tall strings. So tall, in fact, that before the advent of hop harvesting machinery, farm workers had to use stilts to tend the plants. Harvesting hops were so labor intensive before mechanical harvesters were invented that entire families of migrant farm workers took part in the harvesting process, taking advantage of the plentiful work and employment opportunities.