C.C. Beekman’s Bank is the oldest financial institution between San Francisco and Portland, the oldest bank building still existing north of California, and the oldest wooden commercial building still standing on Jacksonville, Oregon’s California Street. How’s that for a pedigree!

Originally established as a gold dust office in 1856, the current 1863 building has been preserved as a museum since Beekman’s death in 1915. Even when the Bank is not open for tours, you can still visit it through our Beekman Bank Nuggets posts. “Nuggets” share museum artifacts, tales of 19th Century banking practices, and the role the Bank played in the community, so join us for this on-going virtual tour!

“Like” Historic Jacksonville, Inc. on Facebook and Instagram for regular history trivia and visit our webpage for a treasure trove of Jacksonville history: www.historicjacksonville.org

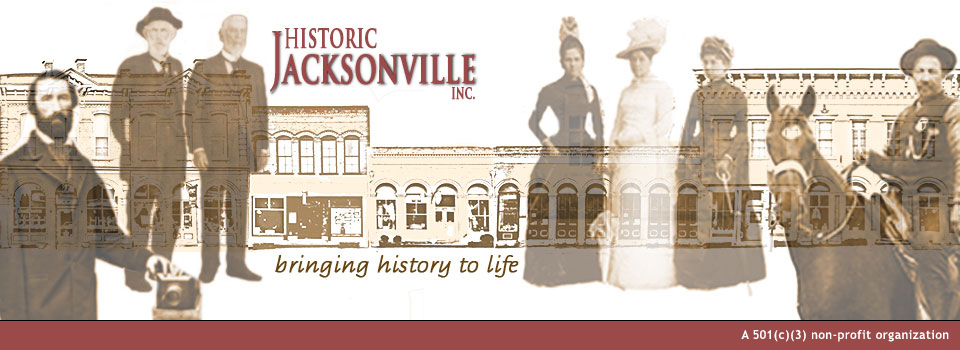

Original Safe

Since Jacksonville’s 1863 Beekman Bank Museum, the oldest financial institution in the Pacific Northwest, is not currently open for tours, Historic Jacksonville, Inc. is sharing some of its many stories. So why do we claim that the Beekman Bank was the Pacific Northwest’s oldest financial institution? It all has to do with this safe!

It’s also a special safe. When Cornelius C. Beekman bought his bankrupt former employer’s stables and corral in 1856, he opened Beekman’s Express. He spent the next 7 years as an express rider carrying mail, parcels, newspapers, and gold over the Siskiyous between Jacksonville and Yreka until he became the local Wells Fargo agent. To keep miners’ gold secure between trips, he also purchased a safe—this safe—the beginning of a “gold dust” office which became the first financial institution north of California!

In 1863, when Beekman sold his express business to Wells Fargo, becoming their local agent and constructing our Beekman Bank Museum, the safe moved with him. It would have been the safe you saw in the Bank vault until 1893 when he purchased the “burglar proof” and “fire proof” safe in the vault today. But being frugal, Beekman would not have parted with his original safe. Instead he probably used it to store documents and letters.

Location! Location! Location!

We did mention that C.C. Beekman’s Bank is the oldest wooden commercial building still standing on Jacksonville’s California Street. All other wooden buildings were replaced by “fire proof” brick structures, given that fire was a major hazard in early Jacksonville. Major fires in 1873, 1874, and 1884 took out most of the original town buildings, even burning right up to the Beekman Bank. Fire insurance was also an incentive for brick. Owners of wooden buildings saw their insurance costs skyrocket. Cornelius Beekman sold fire insurance yet never replaced his wooden building with a brick structure. Why? Possibly the real estate mantra: location, location, location! Beekman’s Bank was next to one of the town wells and pumps. That hose you see could be attached to the pump and used to spray down the building in the event of fire. Admittedly, its efficacy has been called into question given the need for 2 people and the amount of water pressure that could be generated. Its real purpose may have been to reduce the cost of his fire insurance!

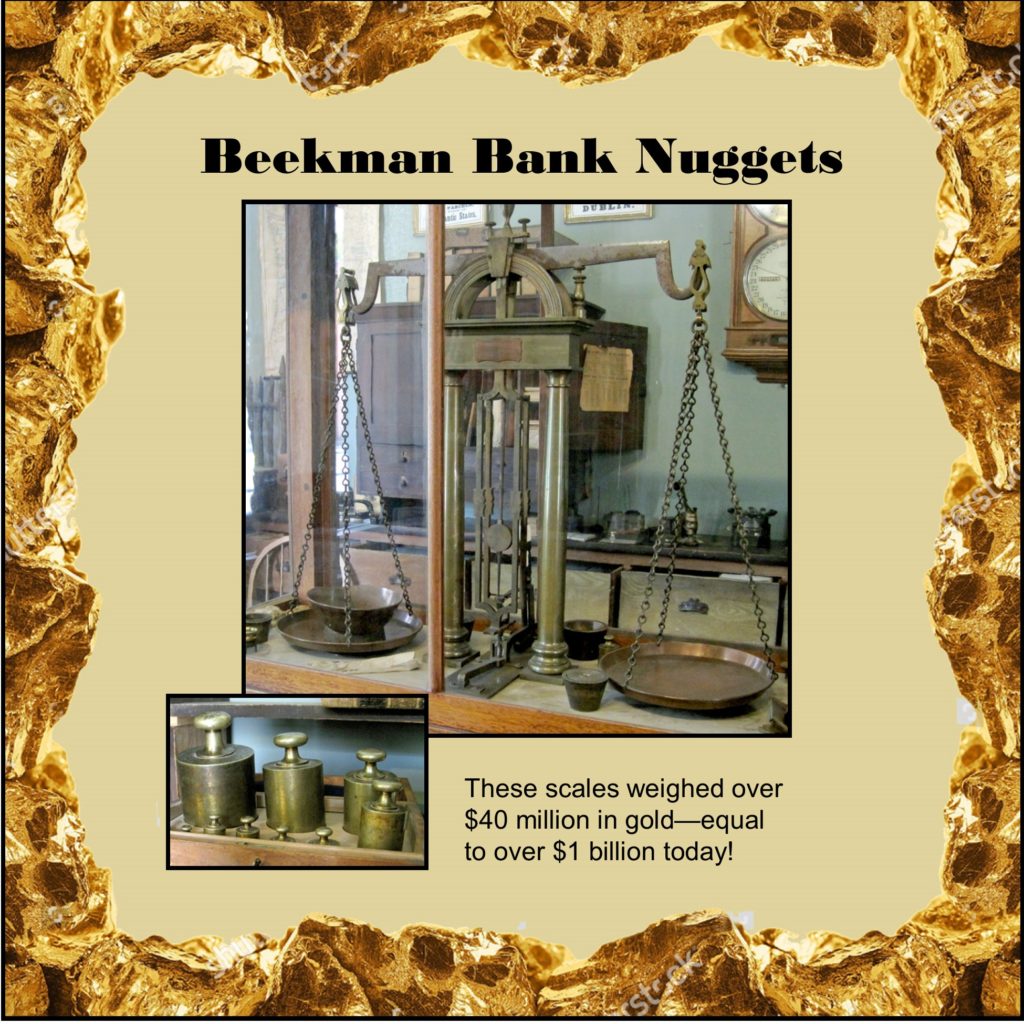

Gold Scales

Occupying the most prominent place on the bank counter is a huge pair of gold scales, purchased by Beekman in 1857 for a reported sum of $1,000. They were known to be the most accurate scales in the region.

Beekman is quoted as saying, “I have weighed enough gold on those gold scales to make a good many men pretty wealthy. [The largest] brass scale weight can weigh 200 ounces, and yet the scales are so delicate that my breath will depress the scale pan. They are full jeweled and were made by Howard & Davis of Boston.” The heaviest weight reported was that of a pan of gold dust and nuggets worth $75,000—at a time when gold was selling for $18-$20 an ounce. Supposedly, over $40 million in gold crossed the Bank’s counters—equivalent to over $1 billion today.

(We might mention in passing that they also weighed many of the children in town–surely valued at more than gold!)

Bank Records and Copy Press

Do you ever wonder how we know so much about Beekman’s banking operations? Cornelius Beekman kept meticulous records of all of his correspondence, orders, and transactions. He used a copy press, the 19th Century version of our copy machines. Letters were placed between moistened sheets of very thin parchment paper. When the machine pressed the pages together, the moist paper would pick up the special ink from the original document. The writing would be reversed from the original but could be read from the back of the sheet. Beekman typically used pre-bound ledger books placing blotting sheets between each entry. Dozens of ledgers still exist containing everything from cigar and oyster purchases to land transactions to running accounts with local merchants to gold shipments.

Clock

When you walk into the bank, it’s hard not to notice the impressive clock hanging on the back wall. It not only keeps the time, it also has a calendar that marks month and day. When Beekman acquired it in 1876, the Democratic Times noted, “C. C. Beekman this week received a splendid clock from San Francisco, which is about the largest and finest in town.” This impressive timepiece was manufactured by the Ithaca Calendar Clock Company based on a patent for calendar clocks obtained by H.B. Horton in 1865. Prior to being offered for sale, the calendar of every clock was run through eight years of days and months, covering 2 leap years. If the calendar registered each date correctly, the calendar movement was considered safe. The clock received an individual number and could then be offered for sale to the public. The company went out of business in 1918, but its clocks are still ticking and are now collector’s items. And almost 150 years later, the Beekman Bank clock still runs!

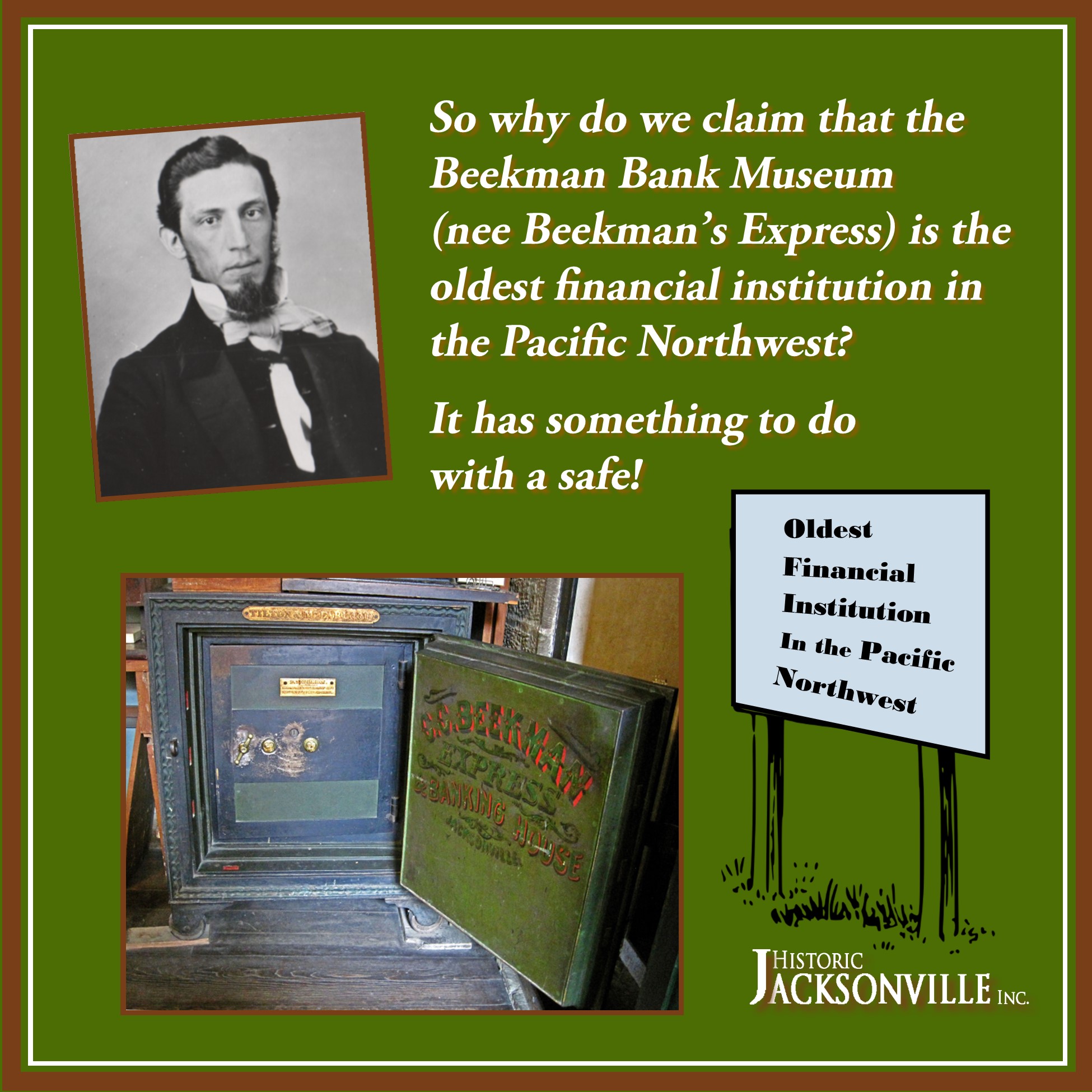

Deringers

Pheasant

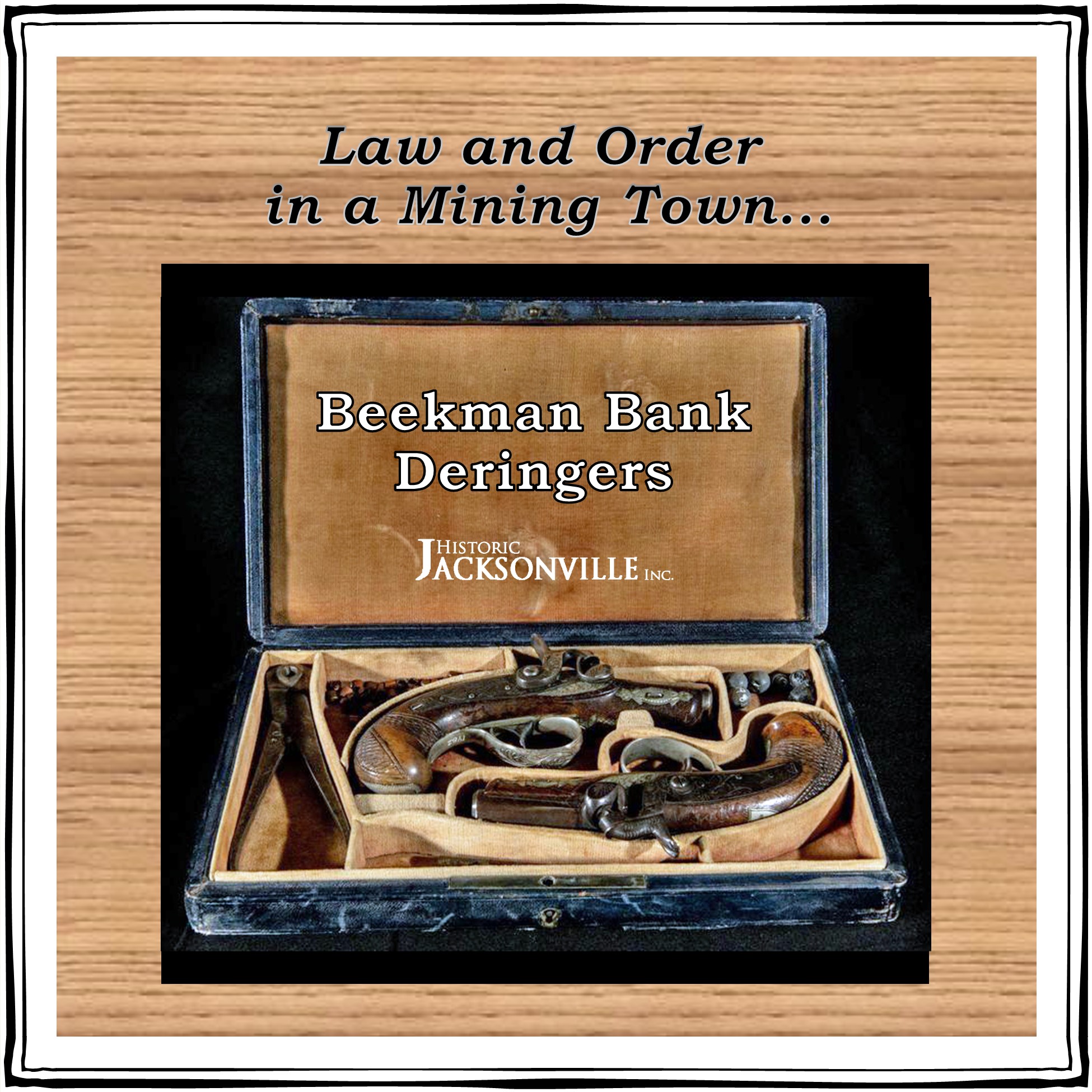

Gold Shipments

Coin Tester

Minimizing Fraud – Canceling and Embossing

We have 2 gadgets today, both designed to minimize fraud. The black gadget is a cancelling machine, essentially a stamp to prevent postage from being reused. Most stamp cancellations today are automated, but hand cancellation is still used for odd shapes and formal mail such as wedding invitations to avoid potential machine damage. The lion’s head machine is an embosser, a stamping machine that creates a raised impression when used. Embossers are also still used today, most commonly on legal papers. Cornelius Beekman used his when signing real estate contracts.

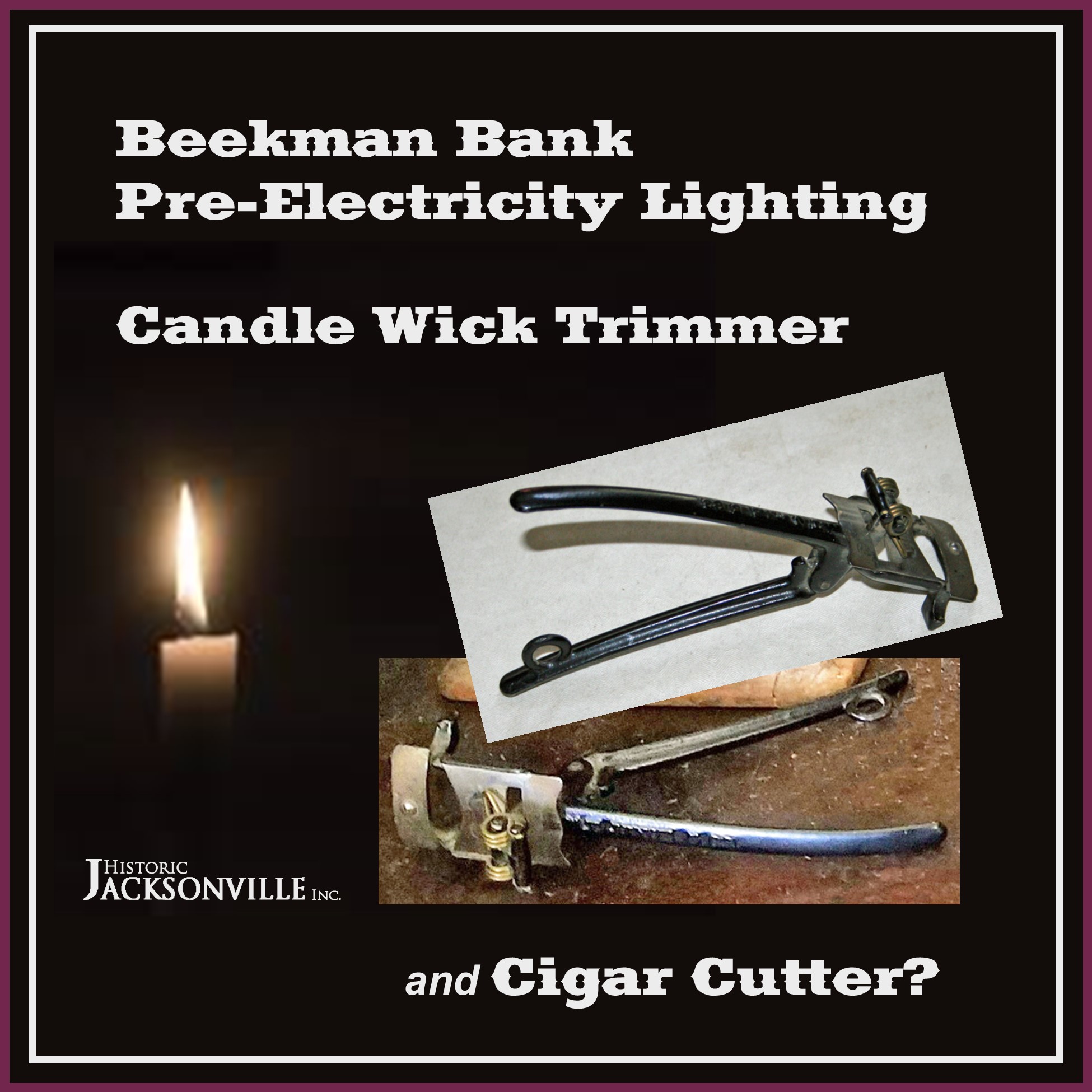

Pre-Electricity Lighting

The bank was not “electrified” until 1906; for most of its institutional life it was illuminated by candles and oil lamps with wicks. To accommodate miners and farmers who labored during daylight, Beekman also held evening banking hours, making illumination even more challenging. His wick trimmer, shown here, would have been used multiple times daily. The candle or lantern wick would have been positioned in the opening, the handle squeezed, and “snip”! The action would have effectively snuffed the light at the same time. (It’s also possible the trimmer might have doubled for clipping the ends off of Beekman’s cigars. We calculate that he smoked about 5 each day since he ordered 1,000 cigars every 6 months!)

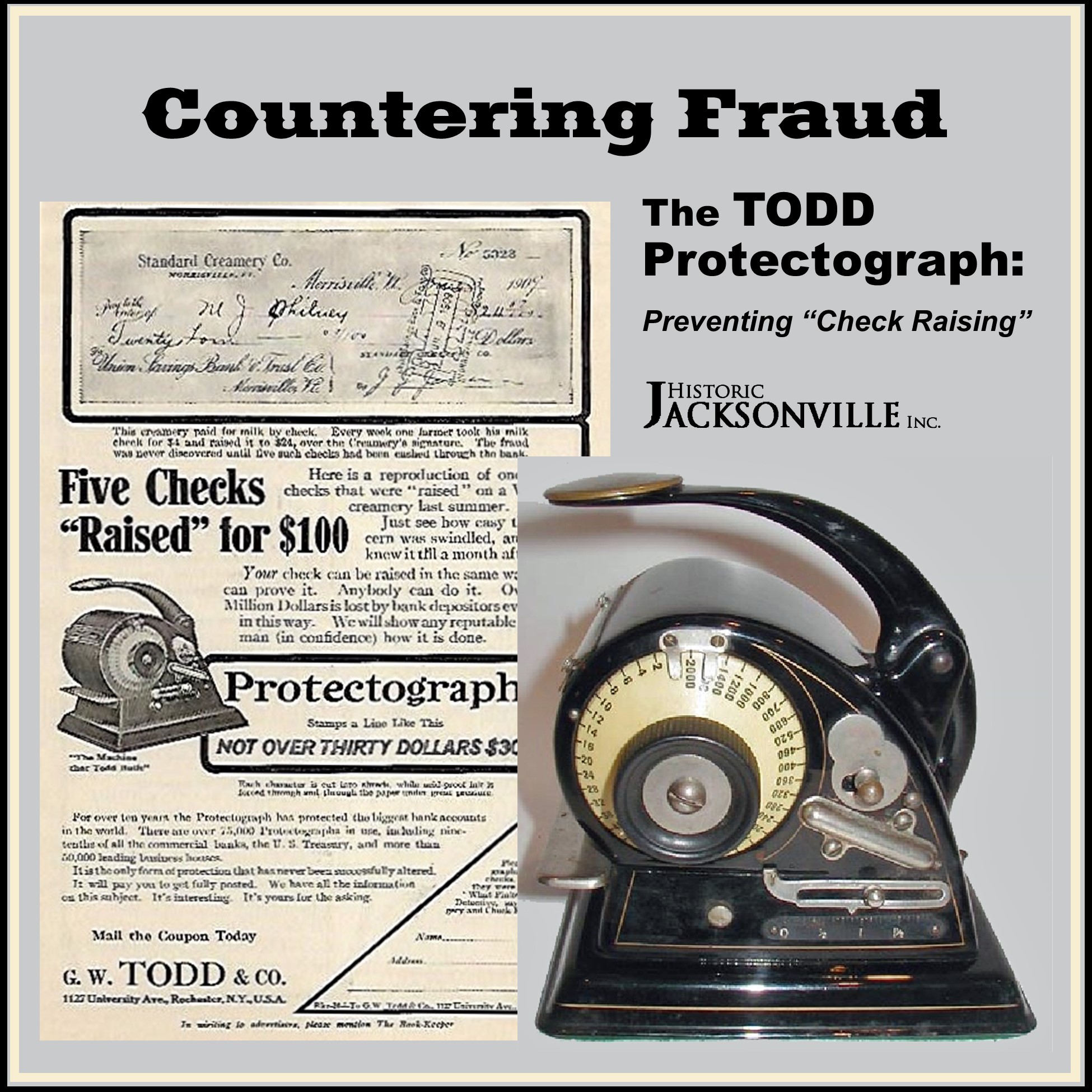

Countering Fraud – The Protectograph

Do you pay bills by checks? Could a check you write have an extra zero or 2 added to it? In the 19th Century, people (including Beekman) didn’t really trust checks. One concern was having a check “raised” (fraudently changed) by the payee. Hence the introduction of various forms of check protection. We’ve previously shared cancellers and embossers. Today we have a check writer which left a numerical impression that was very difficult to alter in a check’s payment amount field. Downward force on the check left very small inked shreds in the paper. The best-known check protectors in the early 1900s had the brand name Protectograph. The Todd Protectograph Co. was established in 1899 by G. W. Todd and made hand-operated mechanical check protectors. Their earliest known ad came in 1902 for the Protector shown here. By 1910, they reportedly claimed that 85,000 Protectographs were in use in businesses. With every Todd Check Protectorgraph came a $1,000 insurance policy in the eventuality a fraudulently raised check did get by.

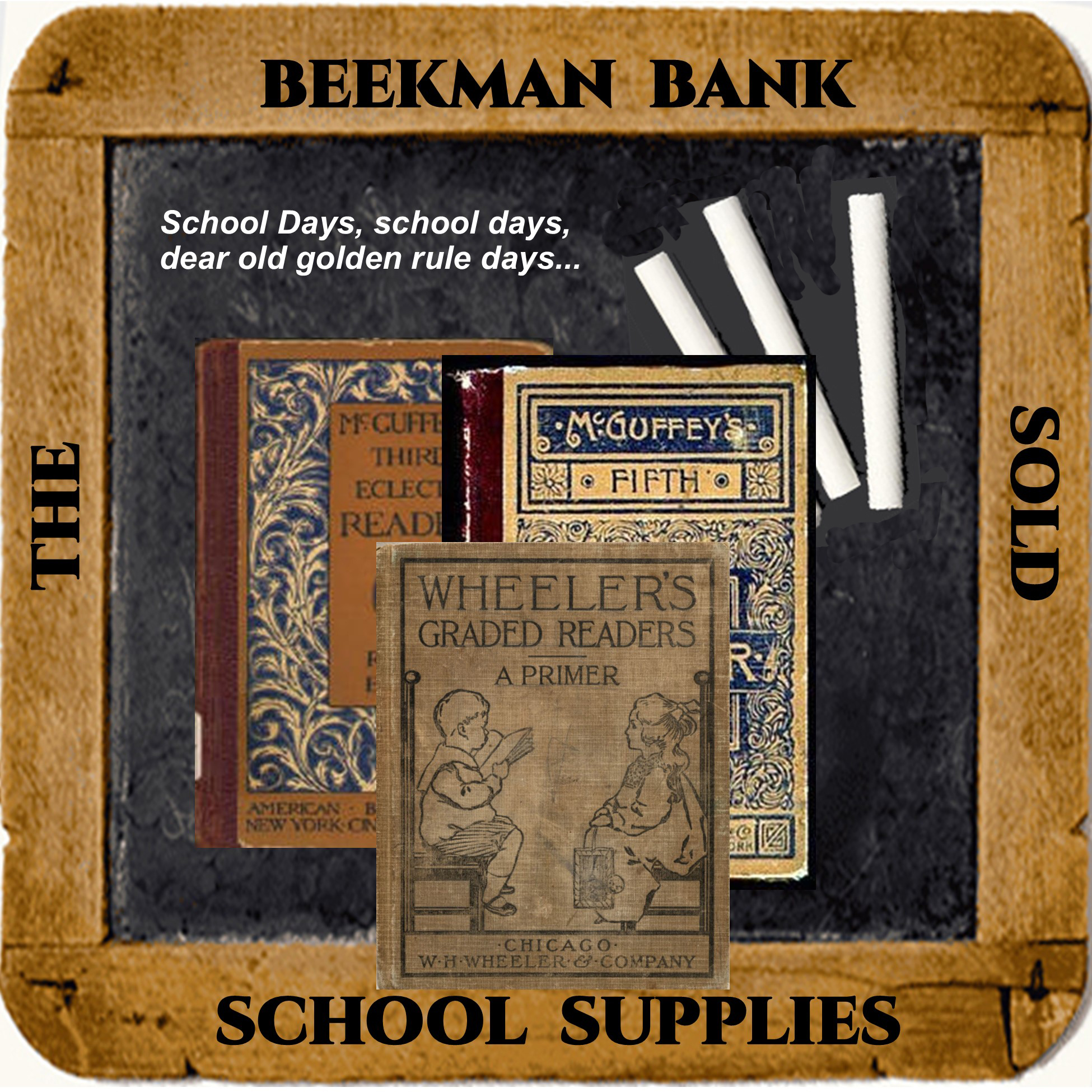

School Supplies

In addition to being a banker, Beekman was an entrepreneur. As early as 1857, Beekman sold schoolbooks out of his express office, later adding other school supplies. There is still a large crate behind the counter of the Bank Museum that contained a shipment of schoolbooks from J.K. Gill.

Once a student had purchased schoolbooks, there apparently was a policy in the late 1800s of simply exchanging new books for old. An 1879 Ashland Tidings issue included a story of “Little Freddie,” who, upon exchanging at the Bank “two old ‘chawed up’ articles that might have once been books for two new ones, rushed breathlessly up to his parental ancestor exclaiming, ‘Oh, papa, didn’t I cheat him though?”‘

We doubt that Beekman felt cheated since he was a major supporter of education. He served on the Jackson County school board as a member or president for many years, donated funds to construct the 1911 schoolhouse, purchased the school bell for the structure, funded college education for several students, served as a Regent of the University of Oregon for 15 years, and was a co-donor of the Failing-Beekman Prize for literature at the University.

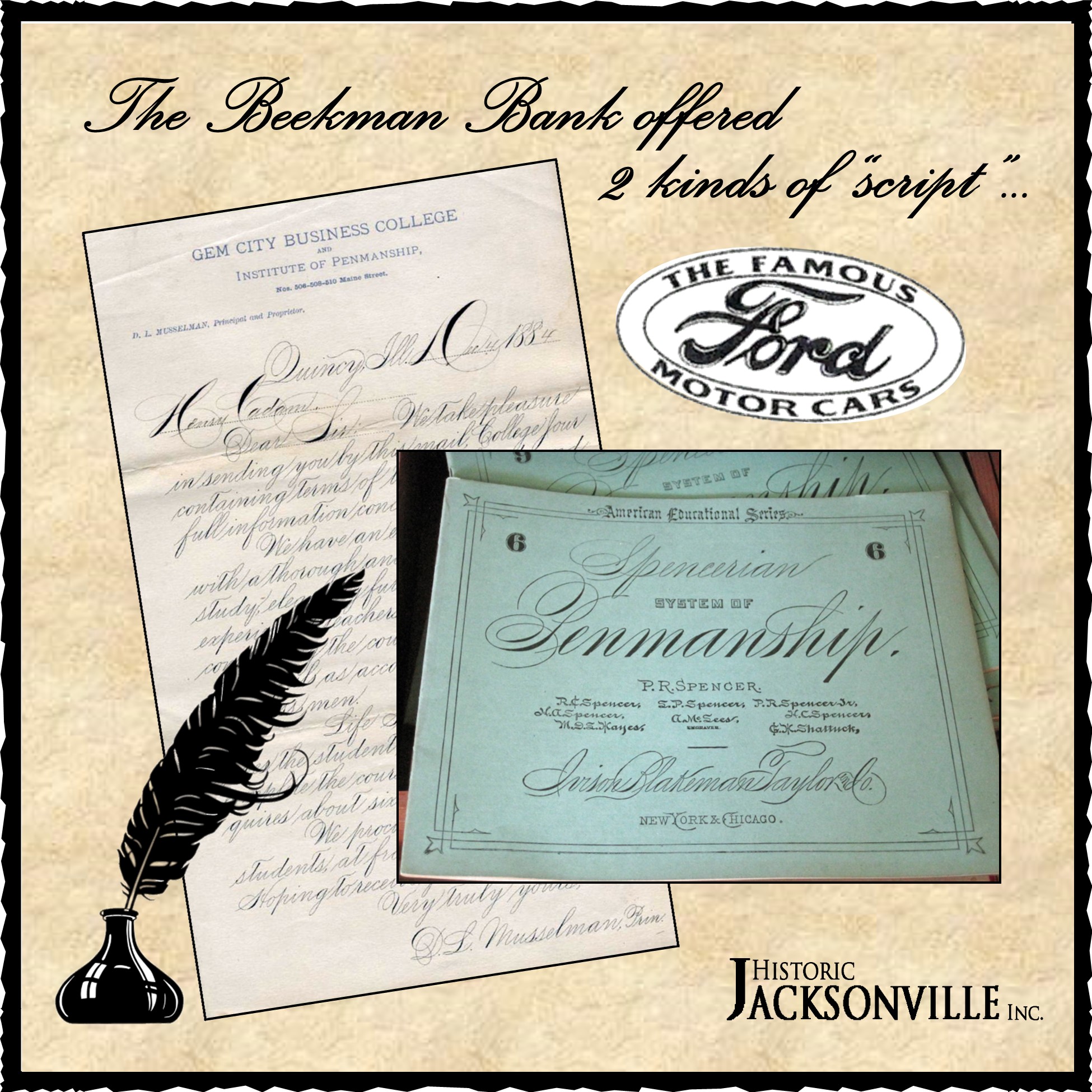

Penmanship Instruction Booklet

We talked last week about Beekman selling schoolbooks and supplies out of the Bank. One of the most popular, and universally used items, was this Spencerian System of Penmanship instruction booklet and the bank still has a drawer full of them! Can you still read script? Platt Rogers Spencer, whose name the style bears, used various existing scripts as inspiration to develop a unique oval-based penmanship style that could be written very quickly and legibly to aid in matters of business correspondence as well as elegant personal letter-writing. Spencerian Script was used in the U.S. from approximately 1850 to 1925 and was considered the American de facto standard writing style for business correspondence prior to the widespread adoption of the typewriter. Spencerian Script is the motif used in many well-known trademarks including Coca Cola and the original Ford Motor Company logo. In other words, paper “script” money was not the only script the Beekman Bank circulated!

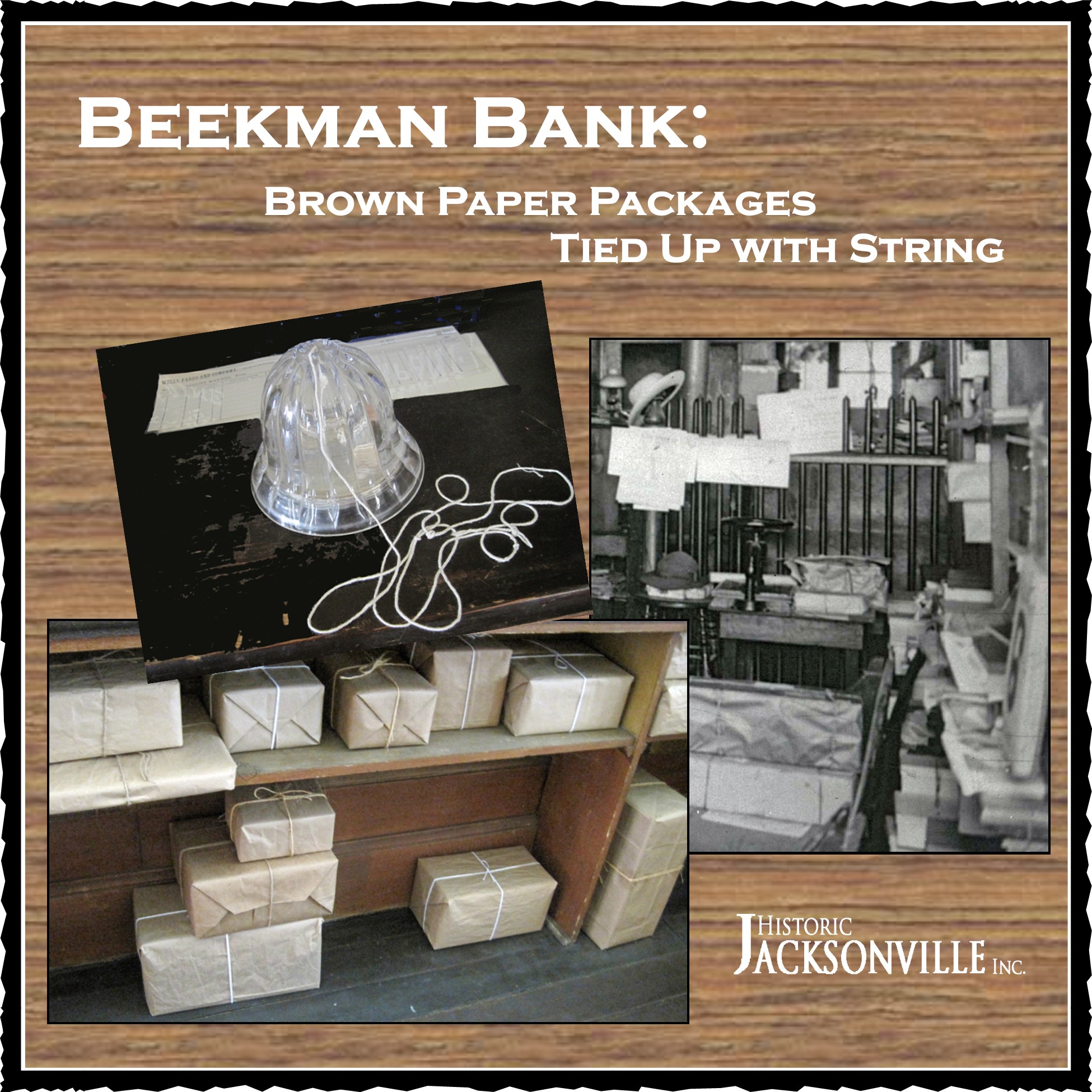

“Brown Paper Packages Tied Up with String”

U.S. government parcel post did not exist until World War I. If you had anything other than mail to ship, it went by an express service, the most prominent of which was Wells Fargo. From 1863 to 1912, Cornelius Beekman was not only the local banker, he was also the Wells Fargo agent. Are you familiar with the “My Favorite Things” song from Sound of Music? Up until the 1930s, if you ordered merchandise or goods, they came packed in a wooden crate or a “brown paper package tied up with string.” At any given time, the Beekman Bank was filled with crates and packages either coming or going. Although various forms of glue have existed for over 6,000 years with bases ranging from sap to fish bladders, masking and Scotch tapes didn’t make their debut until 1925; duct tape in 1942 during World War II.

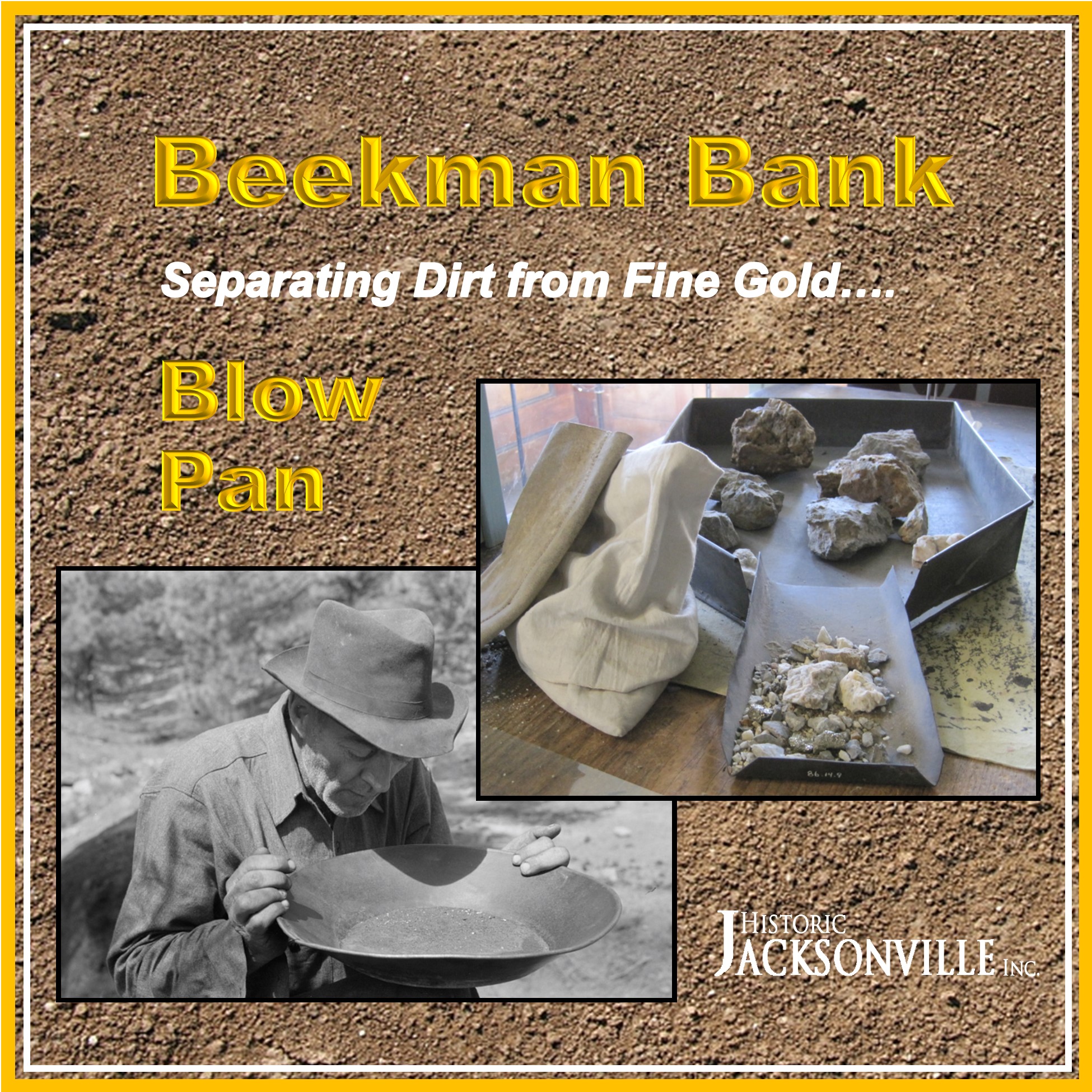

Blow Plan

Dry blowing is a method of extracting gold particles from dry soil without the use of water. A prospector might use it on site by pouring the dirt from a height into a pan, letting the wind blow away the finer dust while the heavier gold particles fall into the pan. Alternately, he might toss the dirt in the air, catching the denser gold particles in the pan while the air blows away the soil. (Think tossing pizza dough.) Beekman would have used the blow pan in the bank to remove remaining impurities prior to weighing gold dust on his scales and assigning a value to the miner’s bank “deposit.” He would have softly blown into the narrow end of the blow pan, sending lighter dust particles into the larger tray while the heavier gold dust stayed behind in the removable tray. He could then easily transfer the gold dust to his scales.

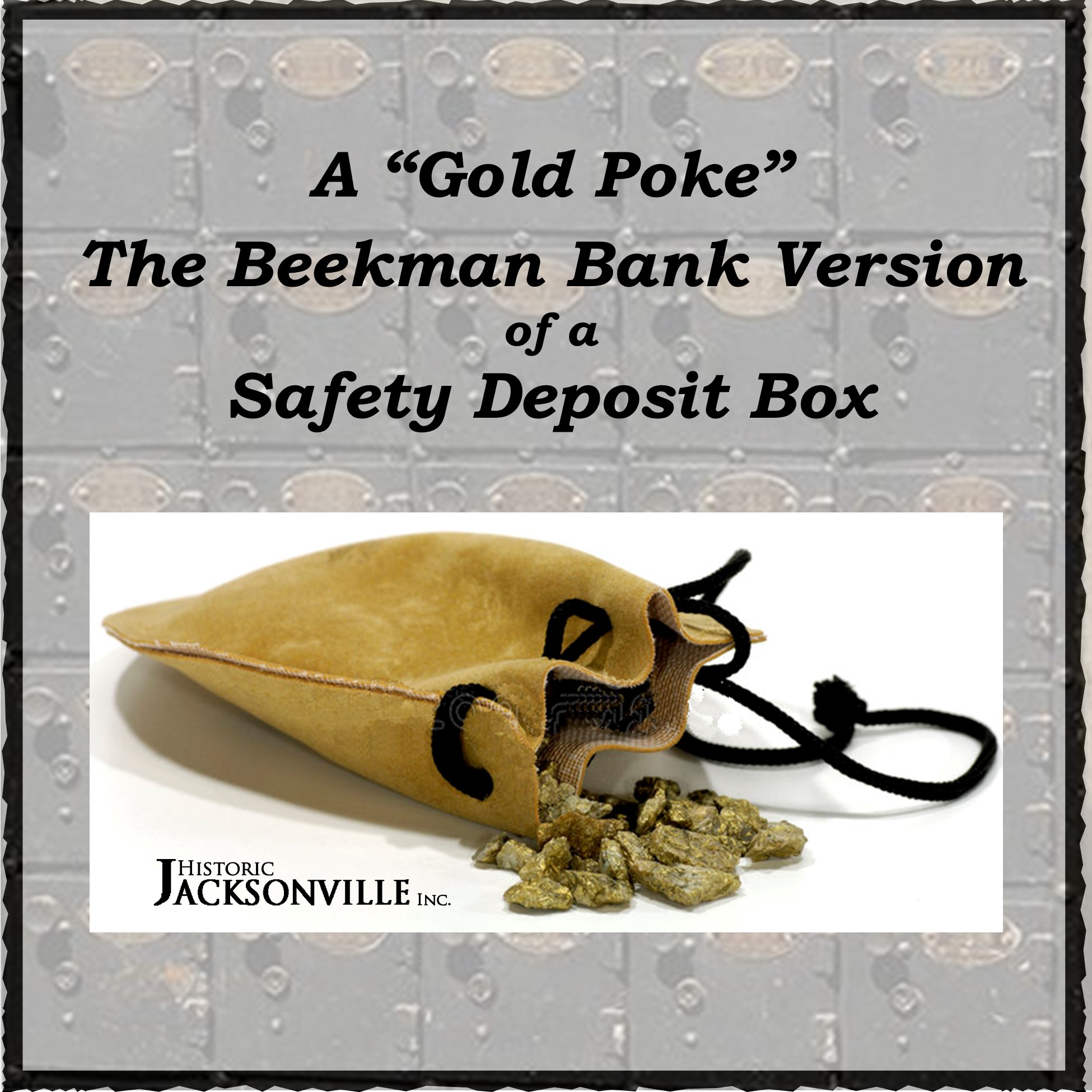

Gold Poke or Purse

Up until the late 1890s, gold dust was an acceptable form of currency. Every saloon, store, and payment office in Jacksonville would have owned a gold scale to measure gold for payment. Miners carried their nuggets and dust around in small sacks, known as “pokes” or “purses,” which essentially served as wallets. Pokes were made from whatever was at hand—leather, canvas, cloth, etc. When miners deposited their gold in Beekman’s Bank, Beekman would weigh it, assign a value, store the poke in his safe with the miner’s name on it, and enter the value in his ledger. The poke essentially became a miner’s safety deposit box and bank account. When a miner needed gold, Beekman would remove the appropriate poke, weigh out the requested amount, and record the transaction in his ledger. When paper and coin currency gained popularity, gold pokes were replaced with bill folds and wallets. But old timers still left their pokes in Beekman’s safe, and, for the 3 years after Beekman closed his bank until his death in 1915, he spent the time tracking down old customers to return their pokes—and gold—to them.

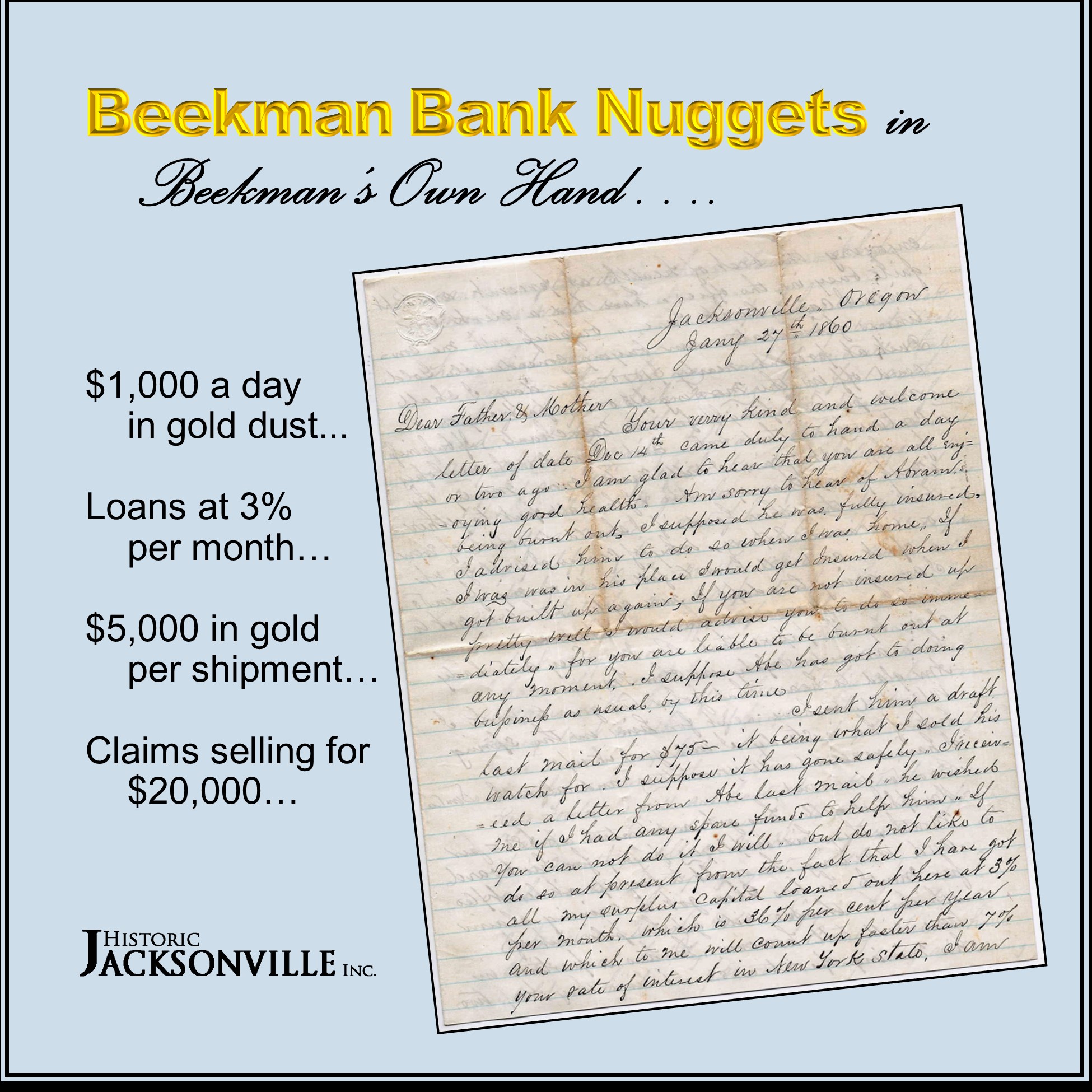

1860 Letter about Bank Operations

We recently discovered some letters Cornelius Beekman wrote his parents during his early Beekman Express years before he became a Wells Fargo agent. In this 1860 letter, he writes of buying $1,000 in gold dust daily; of loaning money at 3% interest per month; of deciding to risk only $5,000 in each express shipment; of new quartz “gold diggins” with claims selling for as much as $20,000; and of the importance of fire insurance after his brother’s business in New York was “burnt out.” Read the transcription of the entire letter at http://truwe.sohs.org/files/beekmanletters.html along with transcriptions of family letters from 1859 through 1915.

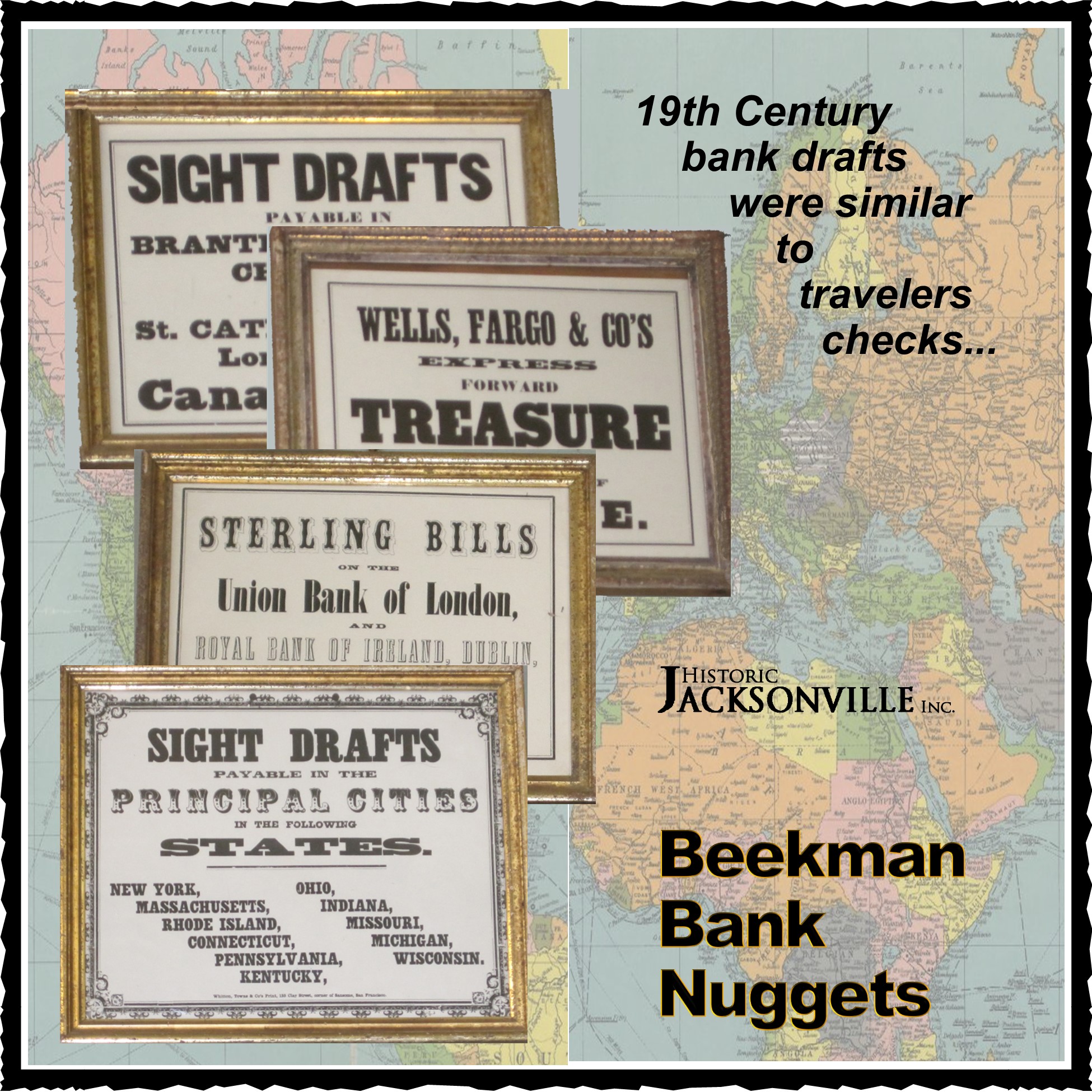

Sight Drafts

The individuals who settled early Jacksonville came from all over the world. Many sought to send monies back to families in their home states or homelands. So how did they do that? By bank drafts—similar to modern-day traveler’s checks. Bank drafts guaranteed that funds were readily available, unlike regular checks where the recipient must wait to see if the cash amount exists. As a Wells Fargo agent, Beekman could provide drafts that would be accepted by financial institutions throughout the U.S. and Europe.

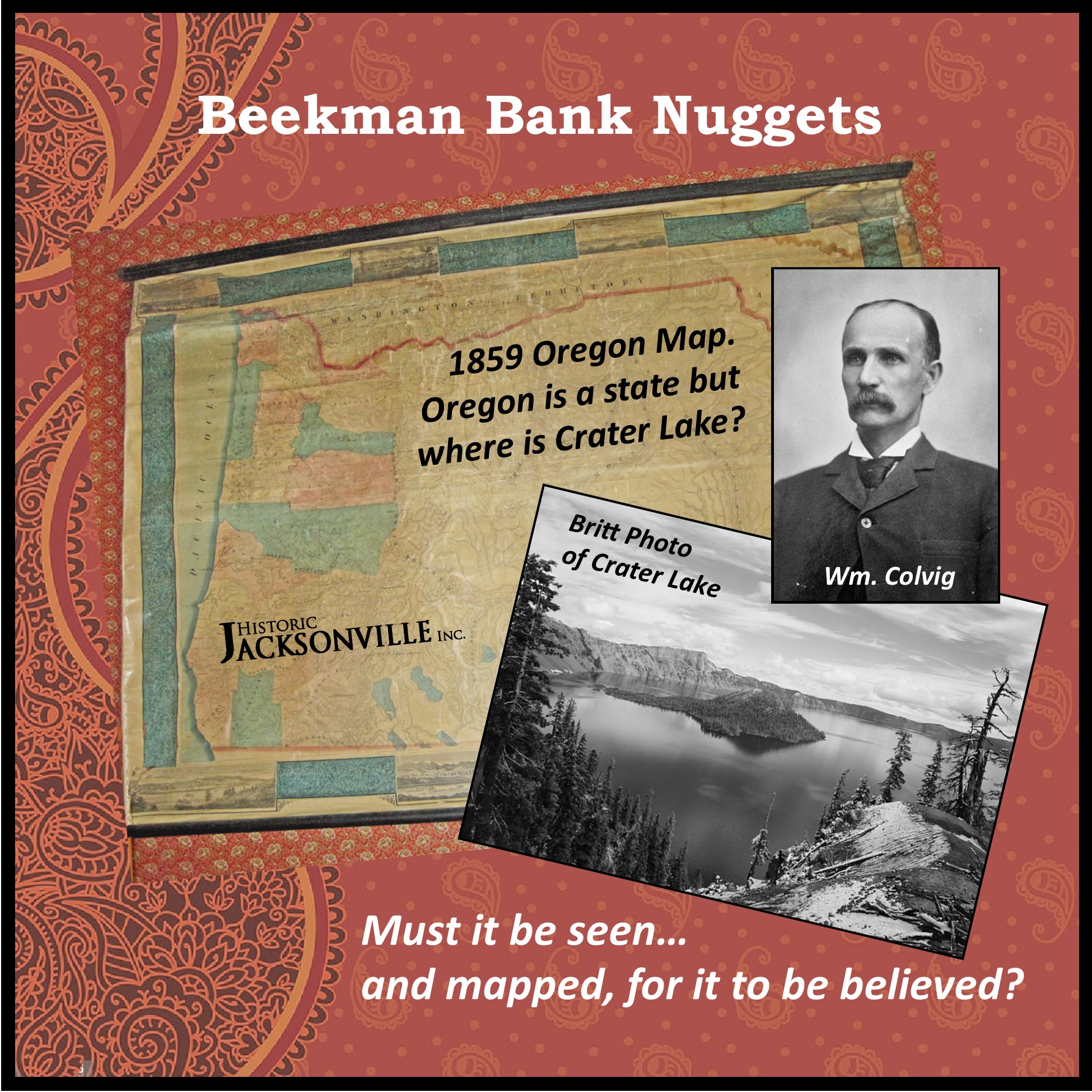

1859 Oregon Map

If the 1859 Oregon map in the room that has been “staged” as Beekman office was pointed out to you, it was probably in the context of “what major landmark is missing?” The answer is “Crater Lake!”

In 1853, Prospector John W. Hillman was reportedly the first European-American to see Crater Lake—and he nearly fell into it. While with a party of miners seeking the storied “Lost Cabin Gold Mine,” Hillman was riding a mule along a high ridge when the animal lurched to a stop and would not budge. Hillman looked down and saw that the beast had come right to the rim of a huge crater with a brilliant blue lake at its bottom. But a lake was of only passing interest when gold was the objective, and it was forgotten until it was discovered by another party 9 years later.

In 1862, Company C of the Volunteer 1st Oregon Cavalry was locating a road between Jackson and Klamath counties. The company came across Crater Lake, which they named Lake Mystic on their maps. A 17-year-old William Colvig, the company clerk, drew a crude map of the area, the first ever made, and the map was sent to Washington, D.C. for copying.

It was an 1869 party of lake visitors that included Jacksonville’s Oregon Sentinel editor Jim Sutton who coined the name “Crater Lake” and published it in the newspaper.

And it was Peter Britt who finally managed to photograph Crater Lake on his 3rd attempt in 1874. The resulting photographs were used to substantiate making Crater Lake a national park in 1902, the 5tholdest U.S. national park and the only one in Oregon.

Wells Fargo Agent

Cornelius C. Beekman came to Jacksonville in 1853 as an express rider for Cram, Rogers & Co. When the company failed, he bought their stables and corral for $100 and established Beekman’s Express, transporting goods and gold between Jacksonville and Yreka. He continued riding that route 2 or 3 times a week until 1863 when he became a Wells Fargo agent, a relationship he maintained until 1905.

U.S. government parcel post did not exist until World War I. If you had anything other than mail to ship, it went by an express service. Cram Rogers and Beekman’s Express had been two of a myriad of small point-to-point express companies. Wells Fargo was one of the “big boys,” and as a Wells Fargo agent Beekman had an assured income for the duration of the relationship.

Only one other large express company that originated in the 1850s remains in service today—American Express. Ironically, Henry Wells and William G. Fargo were 2 of the 3 individuals who merged their New York express companies in 1850 to create American Express. Wells and Fargo created Wells Fargo in 1852 when the other company directors refused to extend American Express service to California, and Wells Fargo became the main express company on the West Coast, later expanding into the rest of the country and Europe.

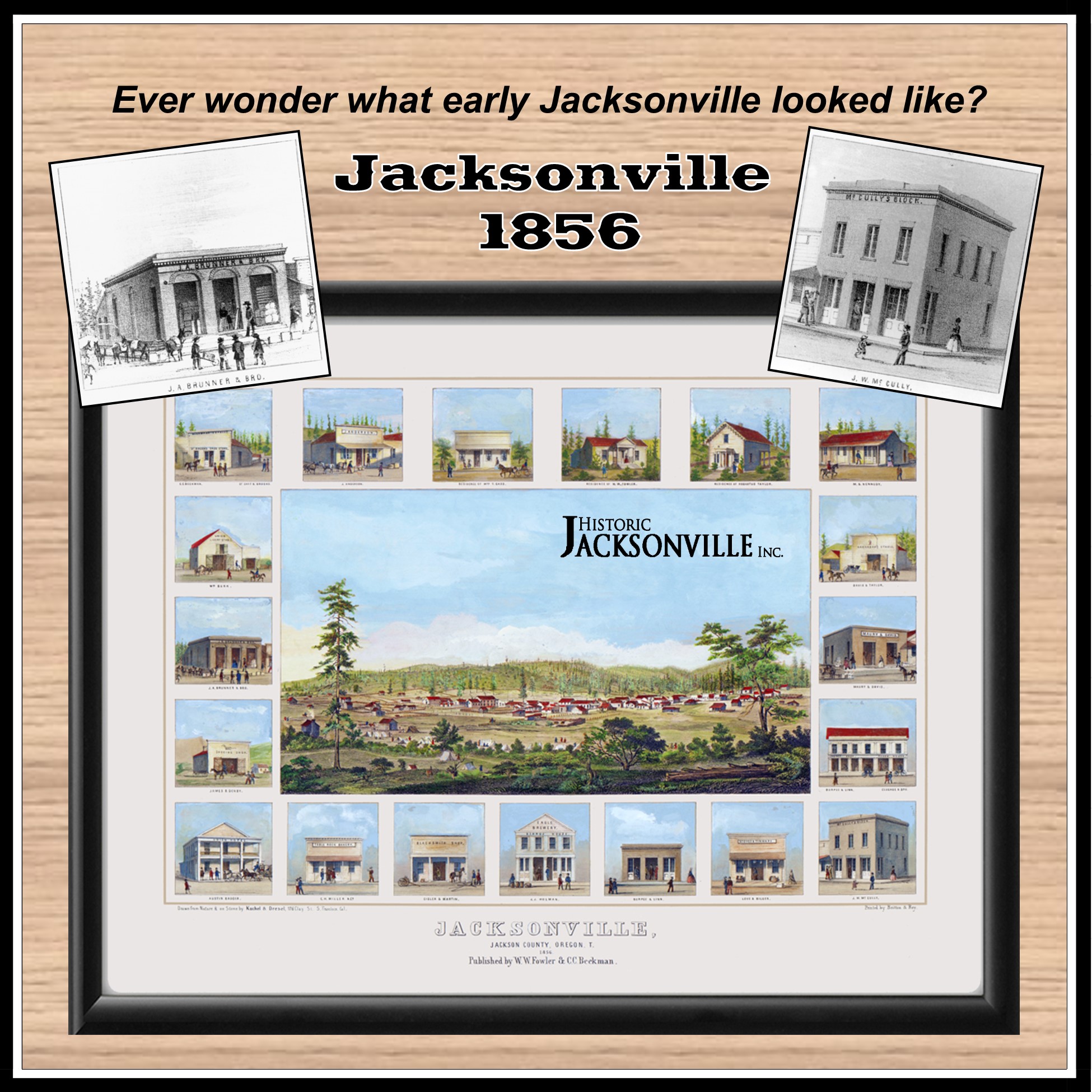

1856 Jacksonville Lithograph

Did you ever wonder what early Jacksonville looked like? You are seeing a colorized version of an 1856 lithograph that hangs on a wall in the Beekman Bank. Created by Kuchel & Dresel, the lithograph depicts etchings of Jacksonville and prominent buildings at that time. The pair went all over California, Oregon, and Washington documenting towns. They typically worked with a local merchant to cover the cost of publication. Cornelius Beekman and W.W. Fowler were the ones who underwrote this print. The original was made by Britton and Rey, famous in the West for their lithographs, using a granite plate that was etched and then printed. Of the buildings depicted, only the Brunner and McCully buildings still stand. The Beekman Express Building is a reproduction based on this lithograph.

The print that hangs in the Bank was found by George Brewer. In 1861, while working with 2 others on the restoration of the U.S. Hotel building, they discovered sheets of paper rolled up inside a wall—5 copies of this lithograph. Each man kept one, and one copy went to the Jacksonville Museum and the last to the Southern Oregon Historical Society. These are the only original prints known to exist although at one time the museum did sell reproductions. SOHS now has the museum’s print as well as its own; one copy was given to the City of Jacksonville; Doug Bishop, who shared this story with us, treasures the copy owned by his grandfather, George Brewer; and the 5th copy hangs in the Beekman Bank.

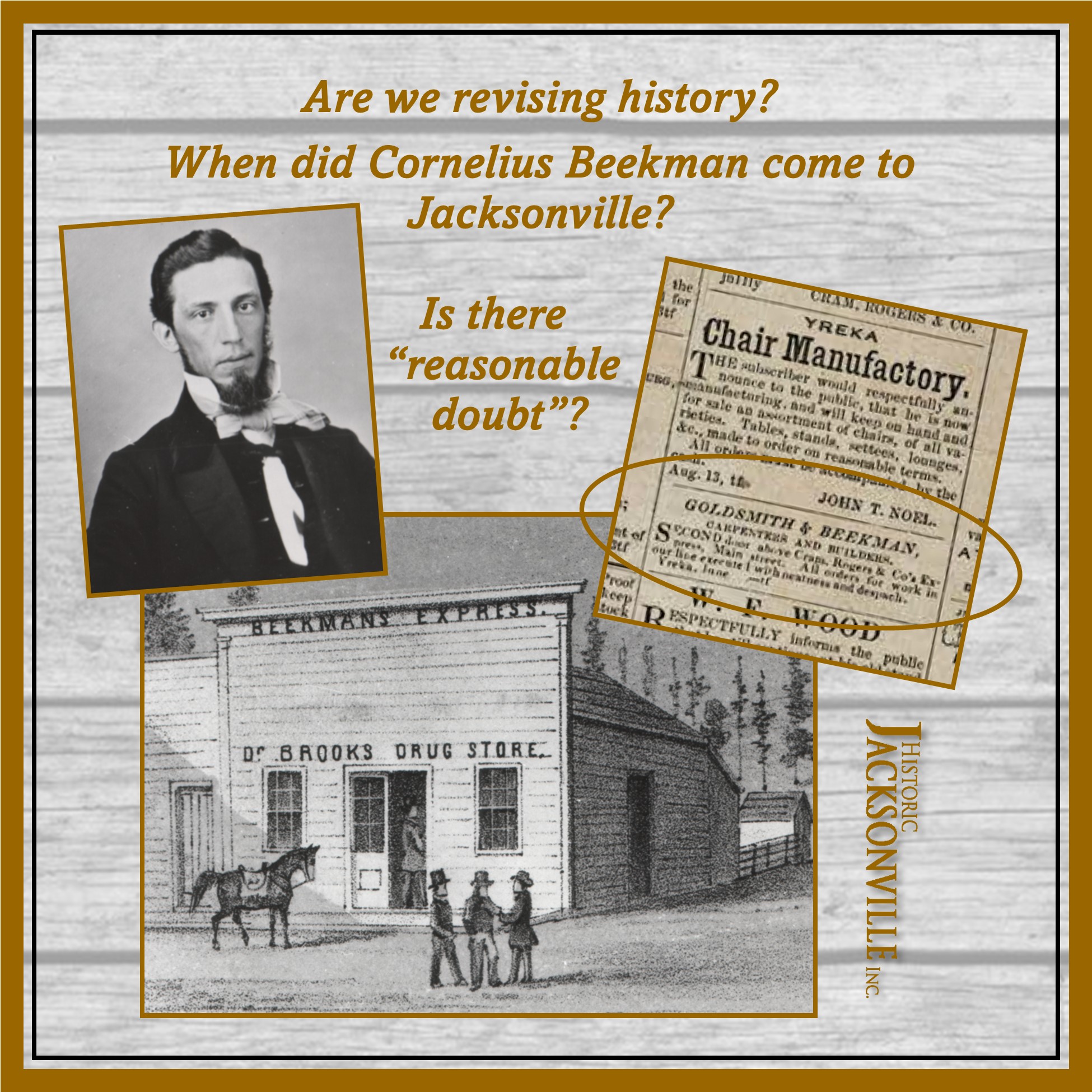

Express Rider to Express Agent #1

For three years before Cornelius Beekman opened the gold dust office that preceded the bank we know today, he was an express rider for Cram & Rogers, carrying mail, parcels, newspapers, and gold over the Siskiyous between Yreka and Jacksonville. We’ve thought for years that Cornelius Beekman moved to Jacksonville in 1853 when he became an express rider between those 2 towns, but it seems he may have remained based in Yreka. When Cram & Rogers went belly up in 1856, he purchased his former employer’s Jacksonville horses and stable and opened Beekman’s Express. That appears to be when he moved to Jacksonville.

Why are we having this change of “heart,” or in this case “history”? Because more contemporary accounts have become available, and we have access to more facts. 1853 Yreka newspapers show Beekman advertising his carpentry and building skills in conjunction with a partner named Goldsmith. Beekman had trained as a carpenter before coming West and periodically fell back on his trade as an income source. We also have access to Jacksonville’s Pioneer Census records and Beekman’s name does not appear until 1856.

Is this sufficient “evidence” to “prove” that Beekman did not move to Jacksonville until 1856? No, but it certainly raises “reasonable doubt” and causes us to rethink our timeline. It may change the details, but it does not change either the bank’s footnote in history or the role Beekman played in turning a gold rush town into the hub of Southern Oregon.

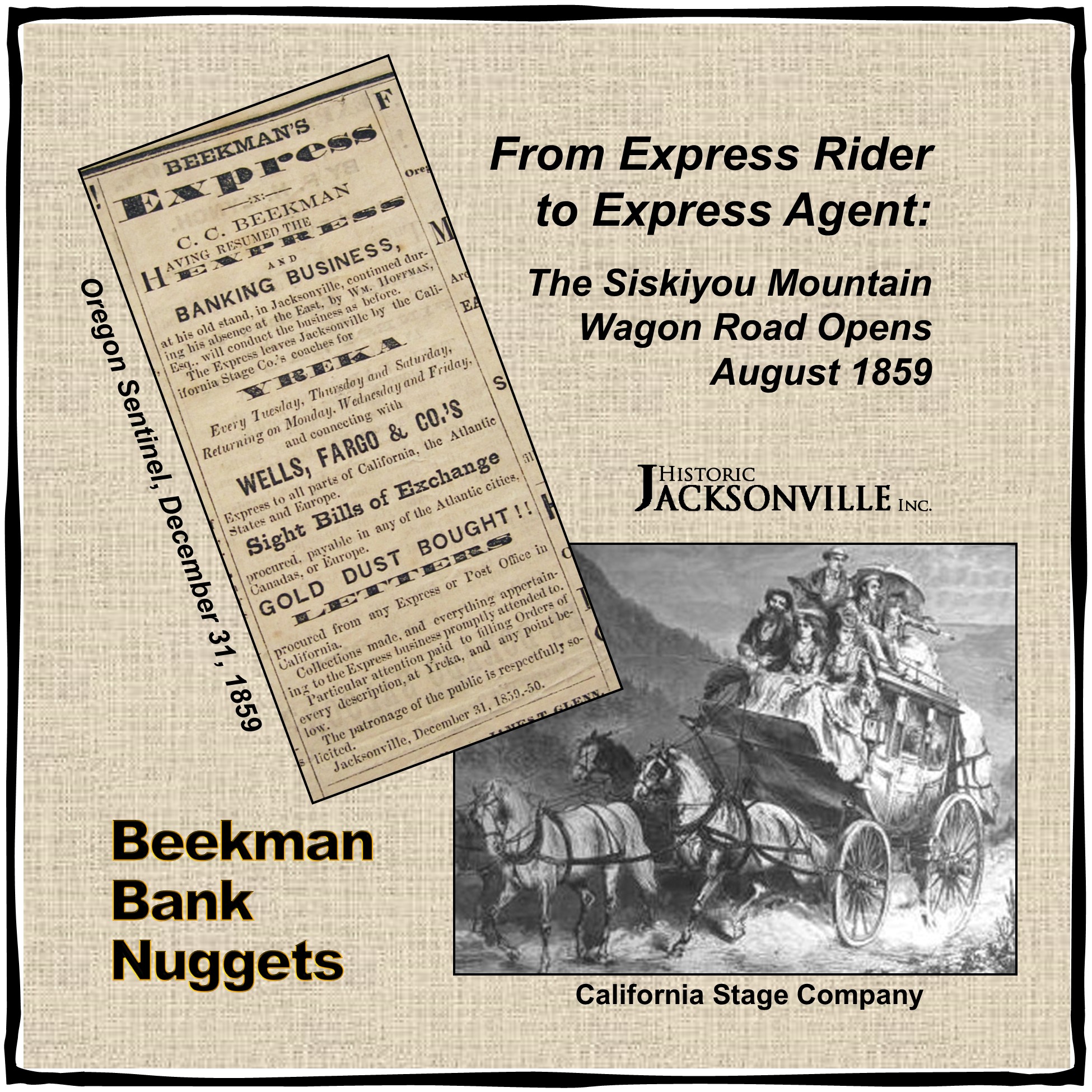

Express Rider to Express Agent #2

As we do more research, we learn new things. Before Beekman built the Bank Museum in 1863, he operated out of his Express office kitty-cornered across California Street. He had come to Jacksonville as an express rider and connecting agent for Cram Rogers & Co. in 1853, making a round-trip ride over the Siskiyous between Jacksonville and Yreka, California, 2 or 3 times a week. When Cram & Rogers went belly up and Beekman opened his own Express in 1856, we thought he continued to make the ride over the Siskiyous himself every week until he became the local Wells Fargo agent in 1863 and constructed the Bank. But it appears that after the Siskiyou Mountain Wagon Toll Road, the first “engineered” road over the Siskiyous, opened in August 1859, Beekman made and received shipments between Jacksonville and Yreka on the California Stage Company’s coaches.

In Yreka, mail, money, parcels, and passengers could connect with Wells Fargo & Co.’s Express “to all parts of California, the Atlantic States and Europe.” We don’t know if Beekman still supplemented the stage schedule with personal trips during winter and spring months when the “road” could be snow, ice, or mire, but this new info just shaved 3 years off the story that’s been told for the past 70 years!

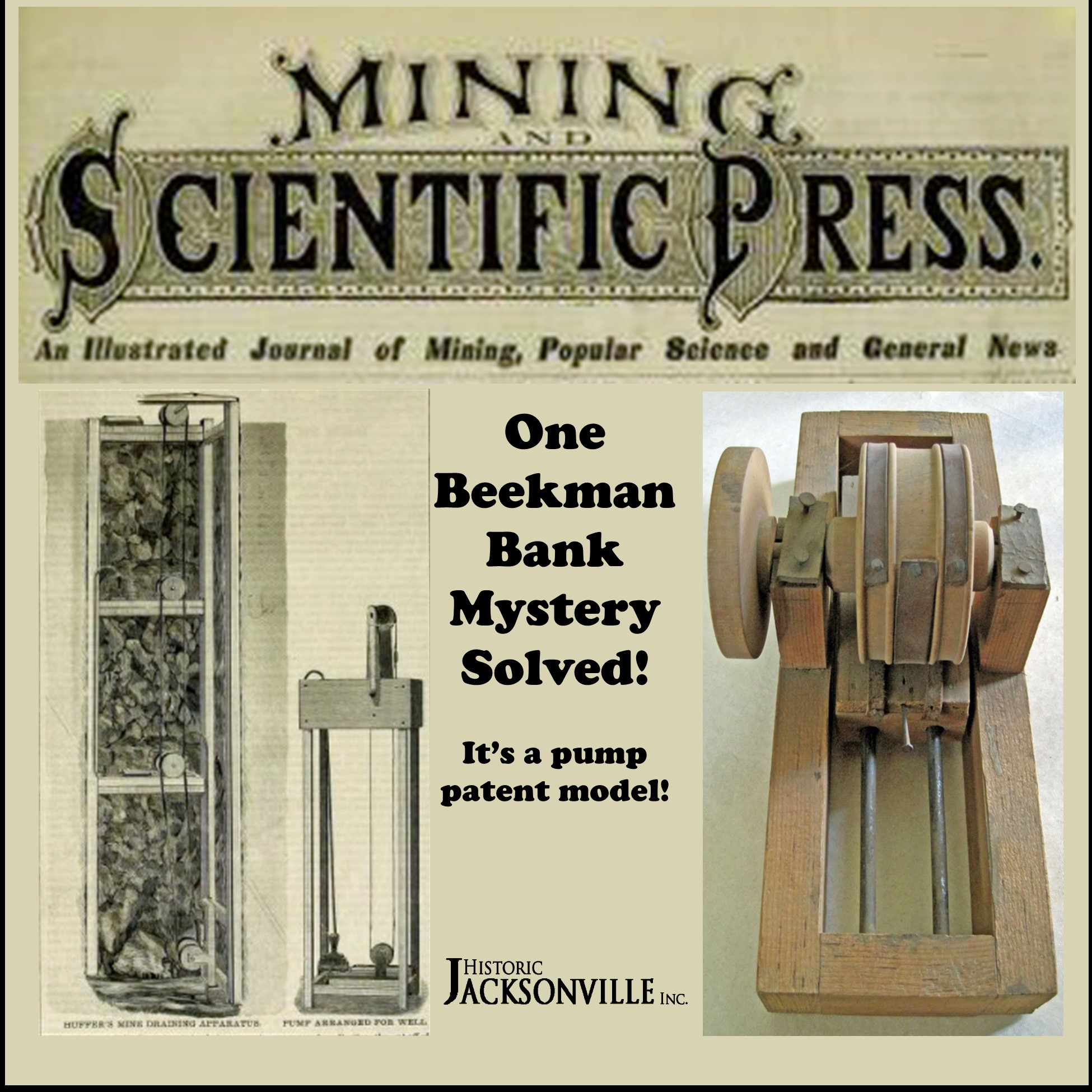

Pump Patent Model

For a long time, we’ve been wondering about the wooden “gadget” in the Beekman Bank vault. Bank docent and “super history sleuth” Ben Truwe finally solved the mystery. Created by Jacksonville resident John Huffer, it’s a model for a patent application for an oscillating pulley system that simultaneously operated multi-level pumps in mines or deep wells. Here’s the introduction to an article in the February 3, 1883, “Mining and Scientific Press” that describes the mechanism:

“Mr. John Huffer, of Jacksonville, Oregon, has just patented through the Mining and Scientific Press Patent Agency a new method of operating pumps in mines or deep wells, where the pumps are located on different levels or stations. The object of the invention is to furnish means for operating all the pumps upon the various levels or stations at the same time by the application of the original power, which, by certain mechanical devices, is transmitted throughout the entire system.”

It was obviously a big deal! And it turns out that John Huffer was not only a craftsman and inventor as his patent readily attests! He also served as a Jacksonville City Councilman and as Jackson County Clerk and Recorder, and he was a partner with Beekman in some mining enterprises.

Bank Robbery!

People have asked if the Beekman Bank was ever robbed. To our knowledge only once, in 1938, long after the bank had been closed and declared a museum. Some guns were the only things stolen. However, there was a “yeggman’s plot to rob the Bank in 1913 that was thwarted by the Pinkerton Detective Agency and the local sheriff. According to the March 17, 1913 Ashland Tidings¸ “Because of its isolation and the lack of police protection it was viewed by the yeggs as ‘soft.’” The Pinkertons had received a “inside” tip to this effect and arranged for men to guard the building and watch incoming trains. As a precautionary move, much of the money in the safes along with valuable papers were shipped elsewhere. After local residents became curious as to why armed men were wandering around the building at night, the sheriff’s office admitted there was a plot to rob the Bank. Once the robbers’ plans became public, the attempt was never made.

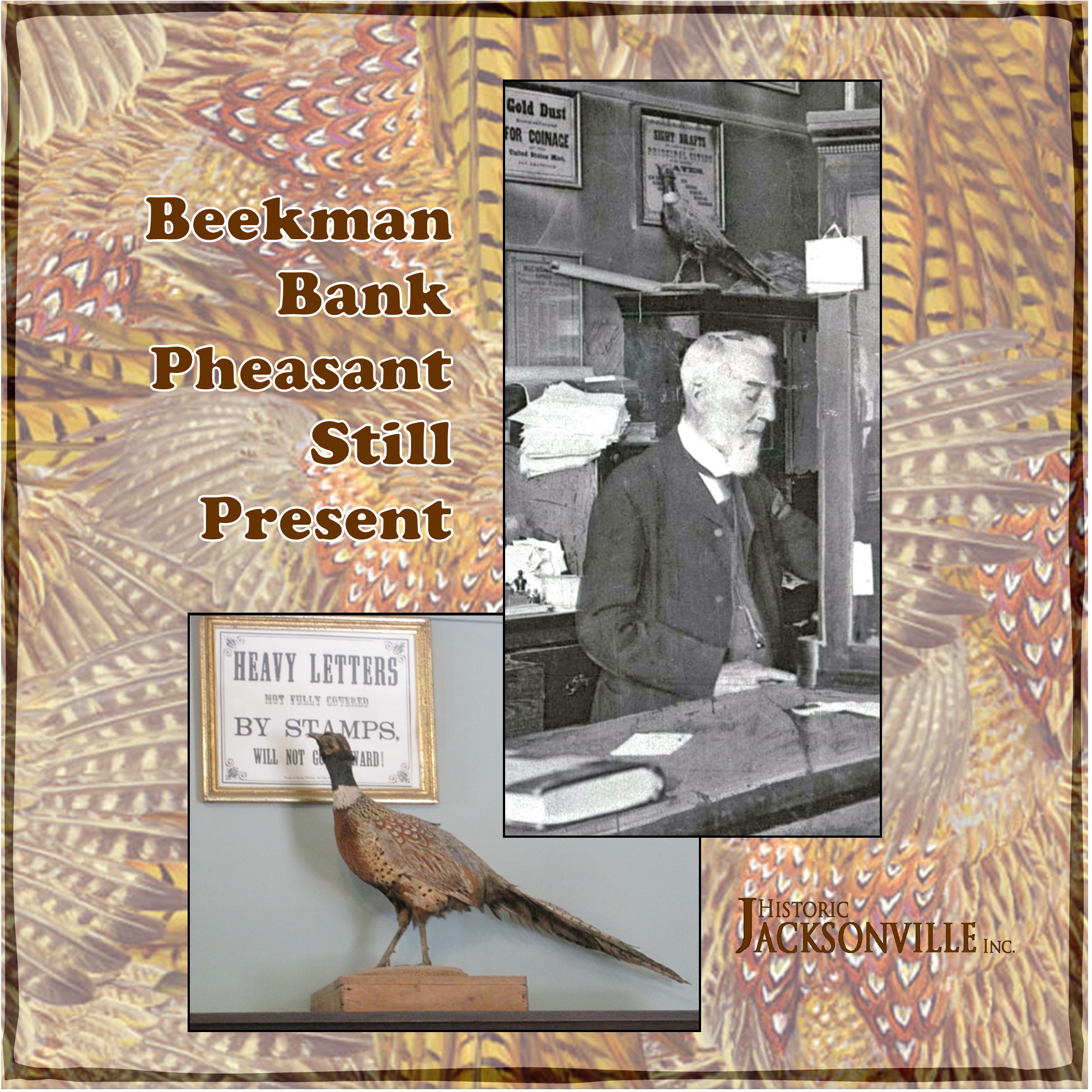

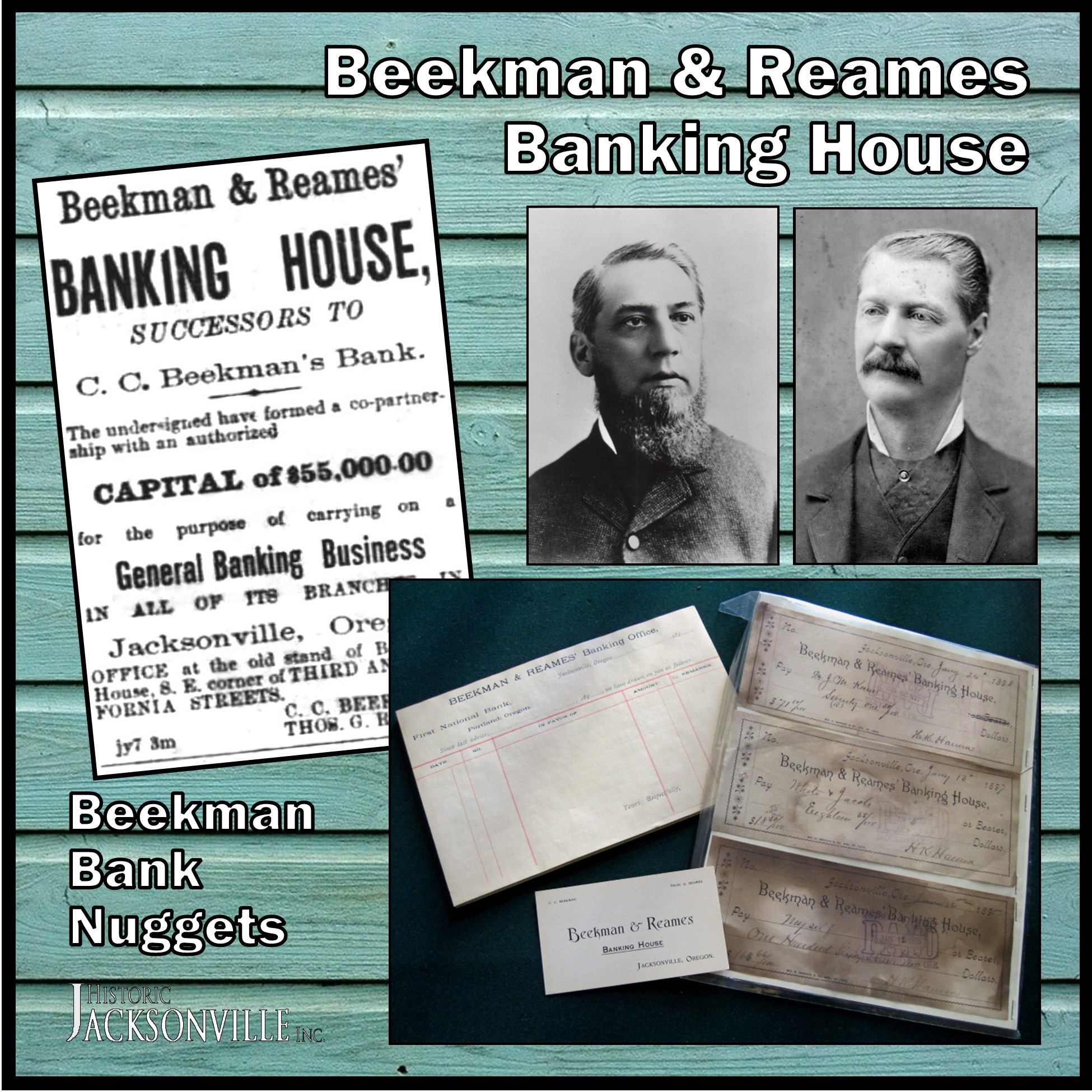

Beekman & Reames

Although known as the Beekman Bank, for some 13 years from 1887 to 1900 Cornelius Beekman was in partnership with his neighbor, Thomas Reames, and the banking house was actually Beekman & Reames. In addition to general banking, Beekman & Reames invested heavily in county warrants and large land holdings.

Reames influence may “modernized” this Jacksonville institution—or at least put more emphasis on appearance. Shortly after the partnership commenced, the Democratic Times noted that “the banking house has been painted, grained and thoroughly renovated, and now presents a very nice appearance.” Less than a year later it was also “embellished with a new sidewalk.” The pheasant that adorns a bank shelf was a gift to Reames, and it’s possible that Reames was the impetus behind the purchase of a typewriter in 1891.

The partnership continued until Reames’ unexpected death in 1900 from complications from a cold. However, Beekman continued to use the Beekman & Reames imprint for some years afterwards—after all, why waste perfectly good stationery, business cards, checks, etc….

Marshmallows

One of the more unusual items found in the Beekman Bank is a tin can that contained Purity Marshmallows. It is noted in family correspondence that Cornelius Beekman had a special fondness for them, and in the early 1900s his daughter Carrie would periodically give him a box as a treat. She may have initially sent him marshmallows from France during her 18-month sojourn in Europe. In the 1800s, French confectioners had taken sap of the mallow plant, used by the Egyptians for medicinal purposes for almost 4,000 years, and whipped it with sugar, water, and egg whites then molded it into bars. It was initially sold as a lozenge. Since Cornelius suffered from sore throats, she may have thought he might find it soothing. Around 1899, candy makers began replacing the mallow sap with gelatin and using corn starch to create molds in which the confection could be shaped. This new version of marshmallows was introduced into the U.S. in the early 1900s. Cornelius Beekman apparently valued his marshmallow treats so highly that he kept them safe in the Beekman Bank vault!

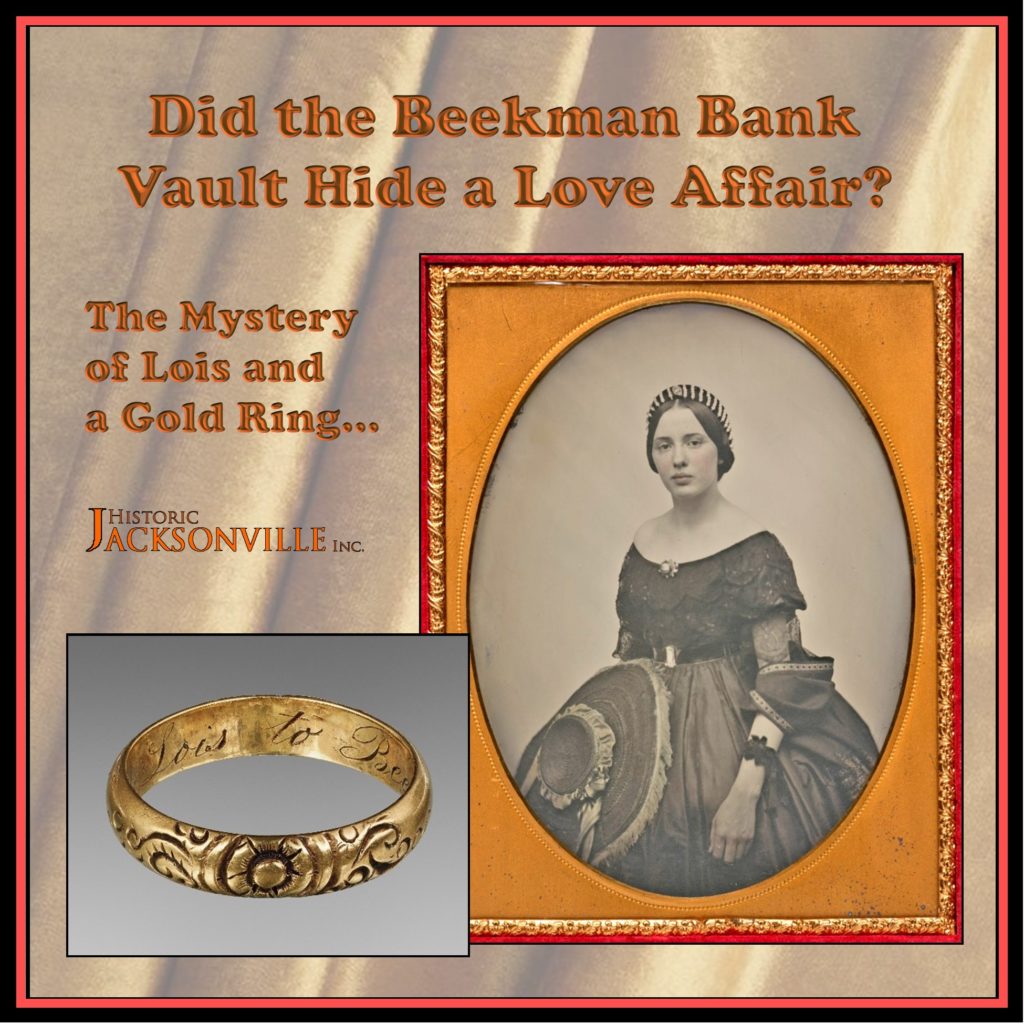

Lois and a Gold Ring

A 1947 inventory of the Beekman Bank listed “what appeared to be a daguerreotype of a lady, in a plush lined case, and another of … C.C. Beekman, in a similar case. Inside this case was a ring (probably gold) inscribed in the inside ‘Lois to Beek.’” These items, found in the vault, were at some point given to the Oregon Historical Society, most likely by Beekman’s daughter, Carrie.

We believe the woman in the portrait to be Lois. But who was Lois? And what was her relationship to Beekman? At this point we can only guess.

The lady appears to be in her late teens or early twenties and, from her clothing, she was quite well to do. Her fashion says “East Coast” and “pre-Civil War.”

A 22-year-old Beekman left New York for California in 1850. It is possible Beek had an “understanding” with Lois prior to leaving. Perhaps he anticipated finding gold and returning home to live near his family. Perhaps he anticipated Lois eventually joining him on the West Coast. But from her appearance, “Lois” does not look like she was cut out for frontier life. And Beekman did not return to New York for an extended stay until 1858—a long time for a girl to wait!

Beekman then spent 9 months with his family before returning to Oregon…alone. A little over a year later, he married Julia Hoffman. Lois apparently became only a memory, but since he kept her photo and ring, it was a memory Beekman apparently treasured.

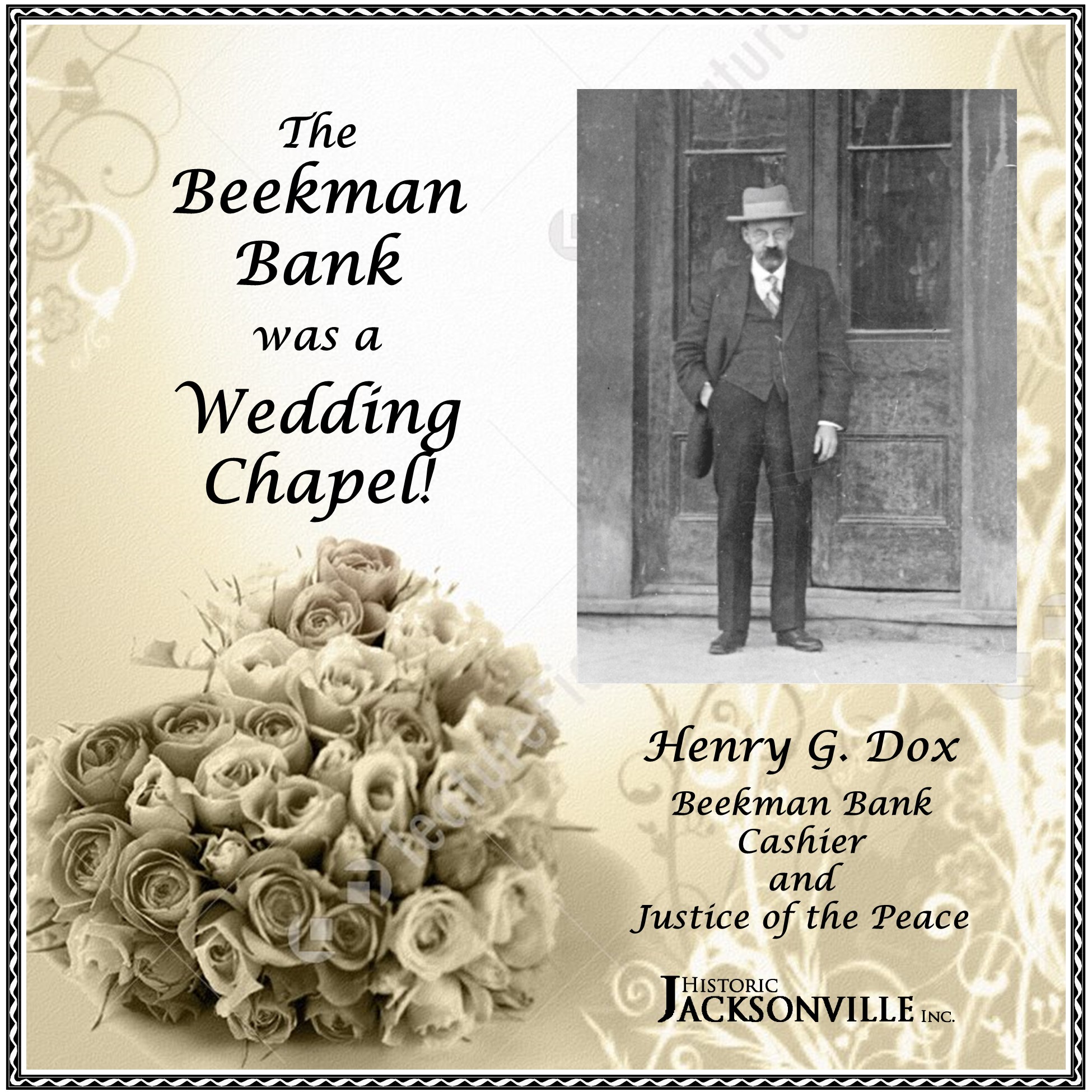

Wedding Chapel

We don’t usually think of the Beekman Bank as a wedding chapel, but at least 2 weddings were performed there and a third originated there.

Henry Dox, Beekman’s cashier from 1903 until the Bank closed, was also a justice of the peace. Marriage license records show him performing weddings in the Bank in both 1911 and 1912. Perhaps a 1910 wedding reported in local newspapers inspired subsequent nuptial couples to call on Dox’s services.

Given the Bank’s late-night hours, Dox frequently slept in the back room of the Beekman Bank. On August 17, 1910, he was roused from his slumbers by A.J. Cole, age 59, and Caroline Clemens, age 49, to perform the marital honors. Cole had been calling on Mrs. Clemens, an old friend, for several months. According to the newspaper account, around 10 p.m. Mrs. Clemens had sighed and observed, “Winter is coming on and I wish I had somebody to carry in the wood and do chores around the house.” Cole promptly replied, “I’m the kid.” Given their ages, they apparently didn’t want to wait a minute longer to tie the knot, and “Justice Dox was brought out from the entrenchments which protect the…Beekman Bank.” The ceremony itself was performed around midnight in a parlor at the neighboring U.S. Hotel.

City Recorder’s Office

Although the back room of the Bank primarily served as a storage area for arriving and departing Wells Fargo shipments, it also served other purposes over the years. In 1881, it served as the Jacksonville City Recorder’s Office, prior to that office being moved to the newly completed town hall, aka Jacksonville’s “Old City Hall” at the corner of Main and Oregon streets. In January of that year, the “Democratic Times” published the following:

“SEALED PROPOSALS WILL BE RECEIVED at the Recorder’s office at Mr. C. C. Beekman’s Bank, until noon of January 31st, 1881, for the sale of a lot and the building now used as the town hall. The lot has a frontage on 3rd Street of 50 feet, more or less, and runs back 100 feet. The Board of Trustees reserves the right to reject any or all bids, as the interests of the town demand. J. NUNAN, Recorder.”

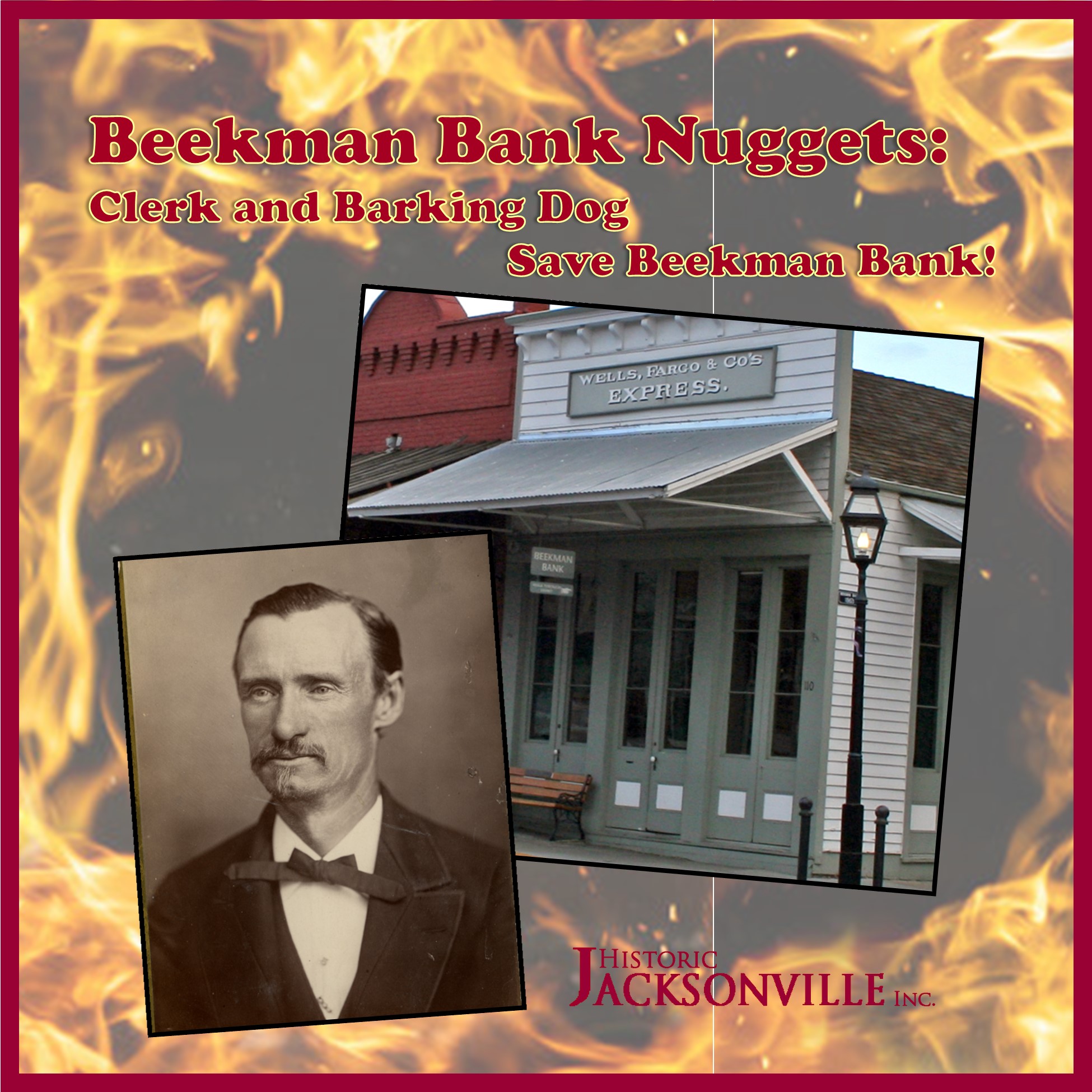

Bank Clerk and Barking Dog

Although the back room of the Bank primarily served as a storage area for arriving and departing Wells Fargo shipments, it also served other purposes over the years. Last week we noted that it had been used as the City Recorder’s office. However, it also provided overnight accommodation for the Bank clerks—at least when late night hours made it more convenient for them to sleep there rather than return home. In a previous “Nugget,” we reported how Henry Dox had been roused from his slumbers in the Bank by a couple who wanted to marry and wished his services as a Justice of the Peace. In 1880, the “Democratic Times” reported that John Boyer, the Bank clerk at the time, was awakened by a persistently barking dog, alerting him to a fire in the rear of the Bank. Someone had deposited hot ashes in a box causing it to catch fire. Thanks to the dog, Boyer discovered it before it could become a full scale “conflagration”!