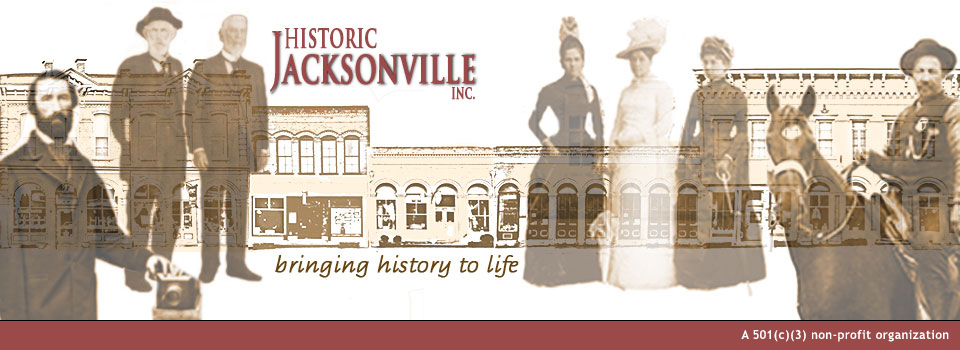

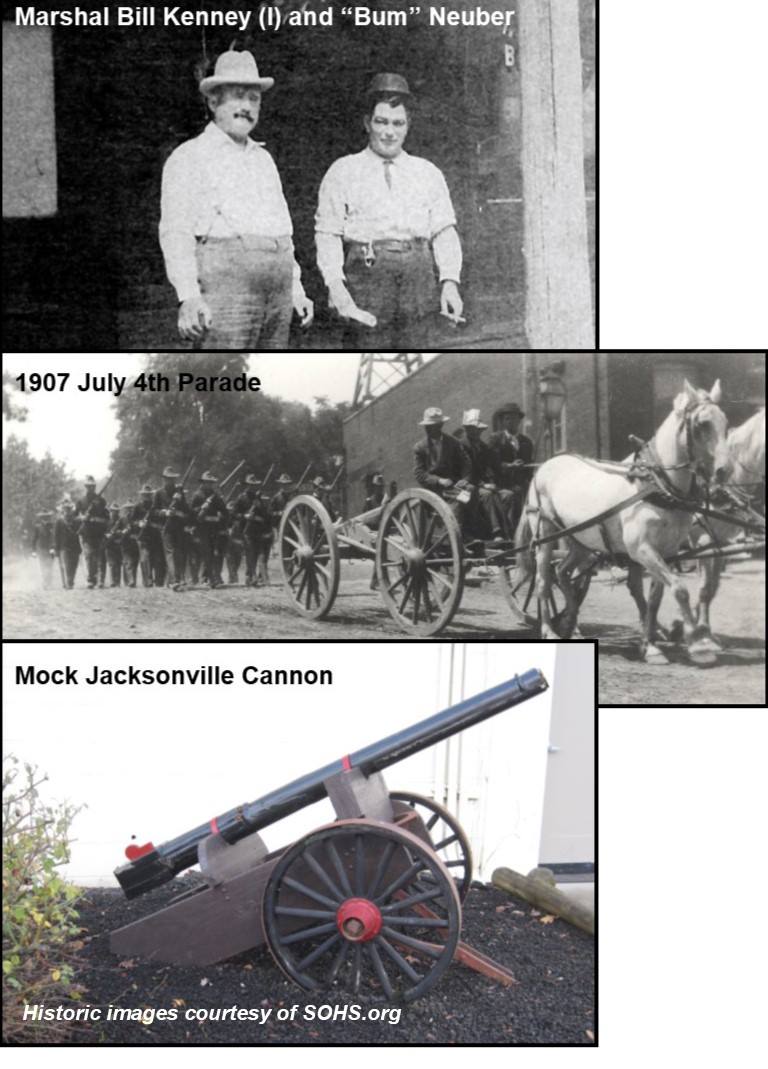

Did you know that Jacksonville used to have a baseball team? The city block on North 5th Street occupied by the local Ray’s supermarket was Jacksonville’s baseball field in the early 1900s, home to the Jacksonville Gold Bricks baseball team. Team owner, George “Bum” Neuber, constructed it in 1902 to take the place of an older field at “Bybee’s Grove,” a mile out of town. Fans could now enjoy a grandstand along with the hotly contested games, but you had to have a ticket! An 8-foot fence blocked the view any casual watchers.

The Gold Bricks were outfitted with blue uniforms trimmed with gold, and the line-up included such well-known local names as Donegan, Nunan, Ulrich, Helms, Armstrong, Orth, Reames, and Wendt. As to their record, well, they won many and lost a few. But then it should be noted that Neuber was known to bring in “guest players” as a means of defeating visiting teams.

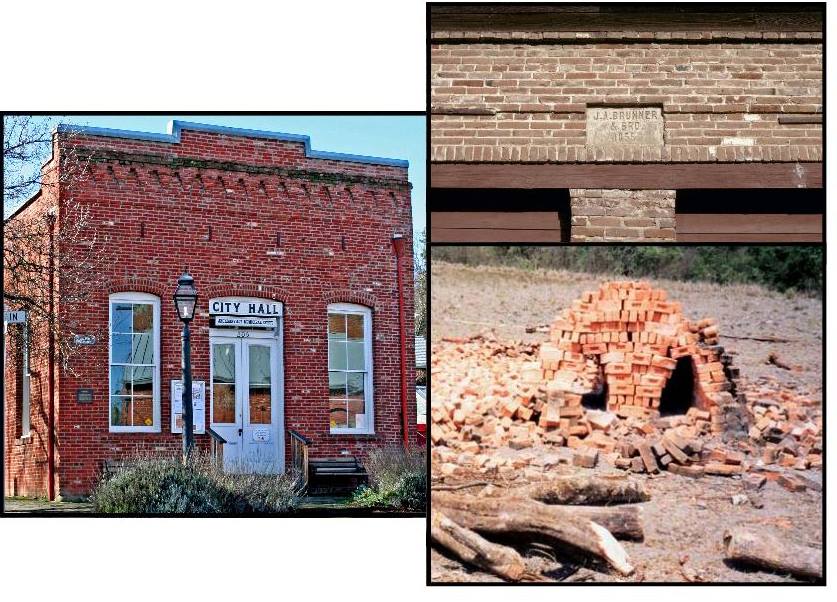

Brick Buildings

Look closely at Jacksonville’s historic brick commercial buildings. Most are second generation structures constructed in the late 1800s after fires wiped out the original wooden buildings. The bricks used in these buildings were fired locally, often on site. They would be stacked into an igloo shape, forming their own kiln, with holes left for the firewood. While convenient, this firing method produced inconsistent results—the middle bricks would be good, but the bricks closest to the fire would be blackish brown and overdone. The bricks on the outside would be peachy pink and underfired. Over and underfired bricks are porous, allowing water to seep through, so most of the Jacksonville brick buildings were originally painted to seal them from the elements.

Broom and Fan Brigades

Our pioneer forefathers didn’t have TV, radio, or movies to entertain them; they had to create their own amusements. Most could play an instrument, sing a tune, or recite a poem when called upon. Tableaux depicting popular images were also frequent in-home entertainment. By the 1880s, inspired by reunions of Civil War soldiers, young ladies began forming drill teams and executing precise drill routines. Manuals were even published to illustrate appropriate movements. Jacksonville is known to have had a scarf team, a fan brigade, and a broom brigade. The latter was especially commended in local newspapers for the way in which it executed the commands of its drill-master “in marching, counter-marching, wheeling, advancing, and handling their ‘deadly weapons.’” Following the brigade’s performance at an 1889 benefit, the teams’ brooms were even auctioned off. The brooms realized the handsome sum of $8 for the cemetery well fund.

By Land or by Sea

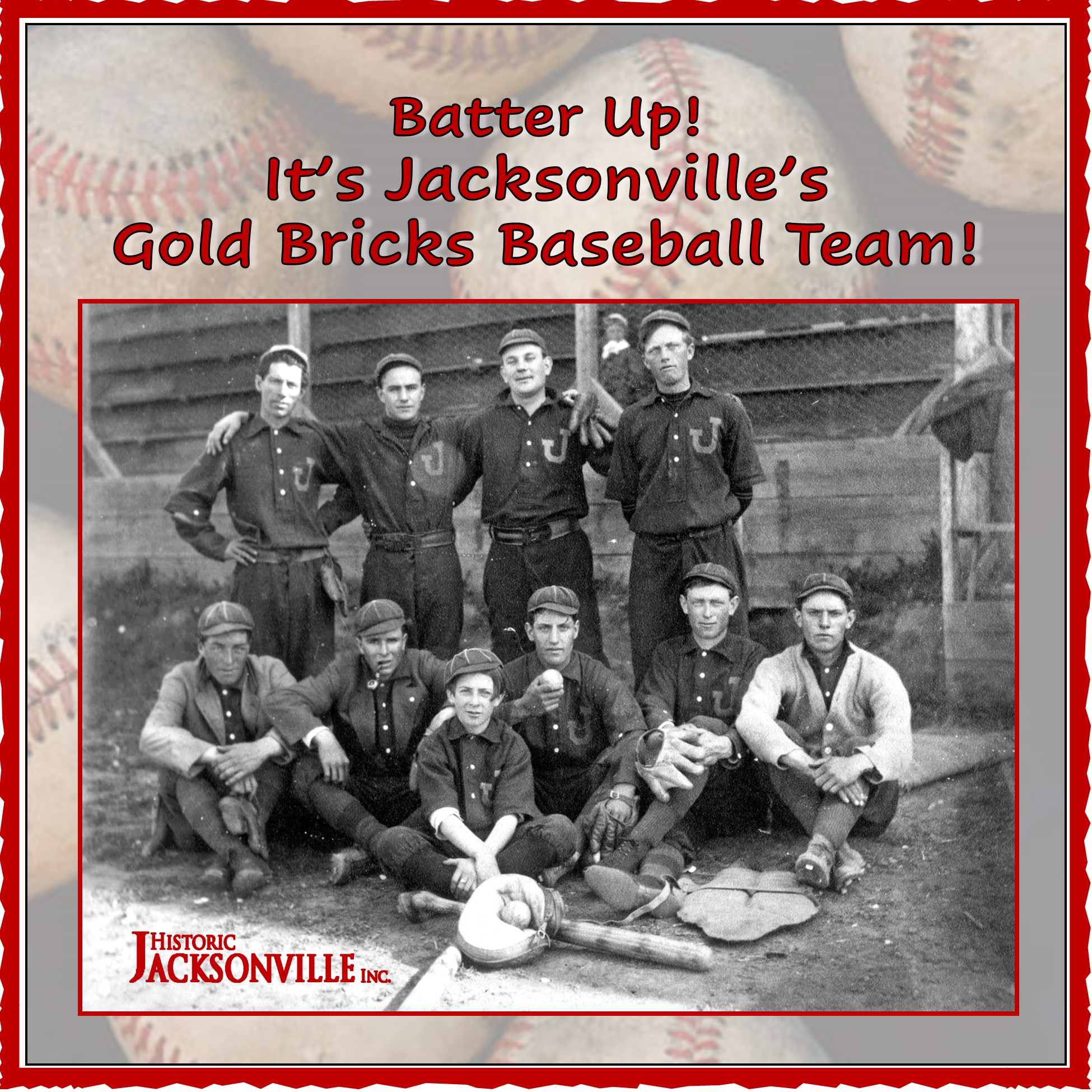

In the early 1850s, Southern Oregon offered the promise of gold and free land. But first you had to get here. There were 2 alternatives—by land and by sea.

By land, you would have traveled up to 6 months in an ox drawn wagon laded with all your remaining worldly possessions, crossing prairies, deserts, and mountains—probably walking much of the way to spare the animals. You would have forded rivers, possibly fought off Indians, run out of supplies, and buried family members along the way. But this overland passage was not viable in winter. The alternatives were a voyage around Cape Horn or a Central American crossing.

By sea, if you chose Cape Horn you would have endured a hazardous trip of 3 to 8 months depending on the wind currents and weather conditions. You would have been jammed in with other passengers, experiencing unsanitary conditions, rough storms, sea sickness, boredom, and a limited diet which often led to scurvy. Or you may have spent three months on a sailing ship (probably in steerage) braving the rocky seas from the East Coast to Panama; crossed the isthmus on foot or by open boat and mule, often in driving rain, while hoping to avoid malaria and yellow fever; then competed for passage to San Francisco. From there it was part boat, part horse or muleback, part “shank’s mare” to the mining fields.

In 1852, if you had made it to the mining camp that became Jacksonville, your home would probably have been a tent; your “kitchen would have been a campfire or cook stove; and your bathroom (assuming you observed the “niceties”) a tree or bush, until you could throw up a shanty and find gold or claim free land.

Would you have made it as a pioneer?

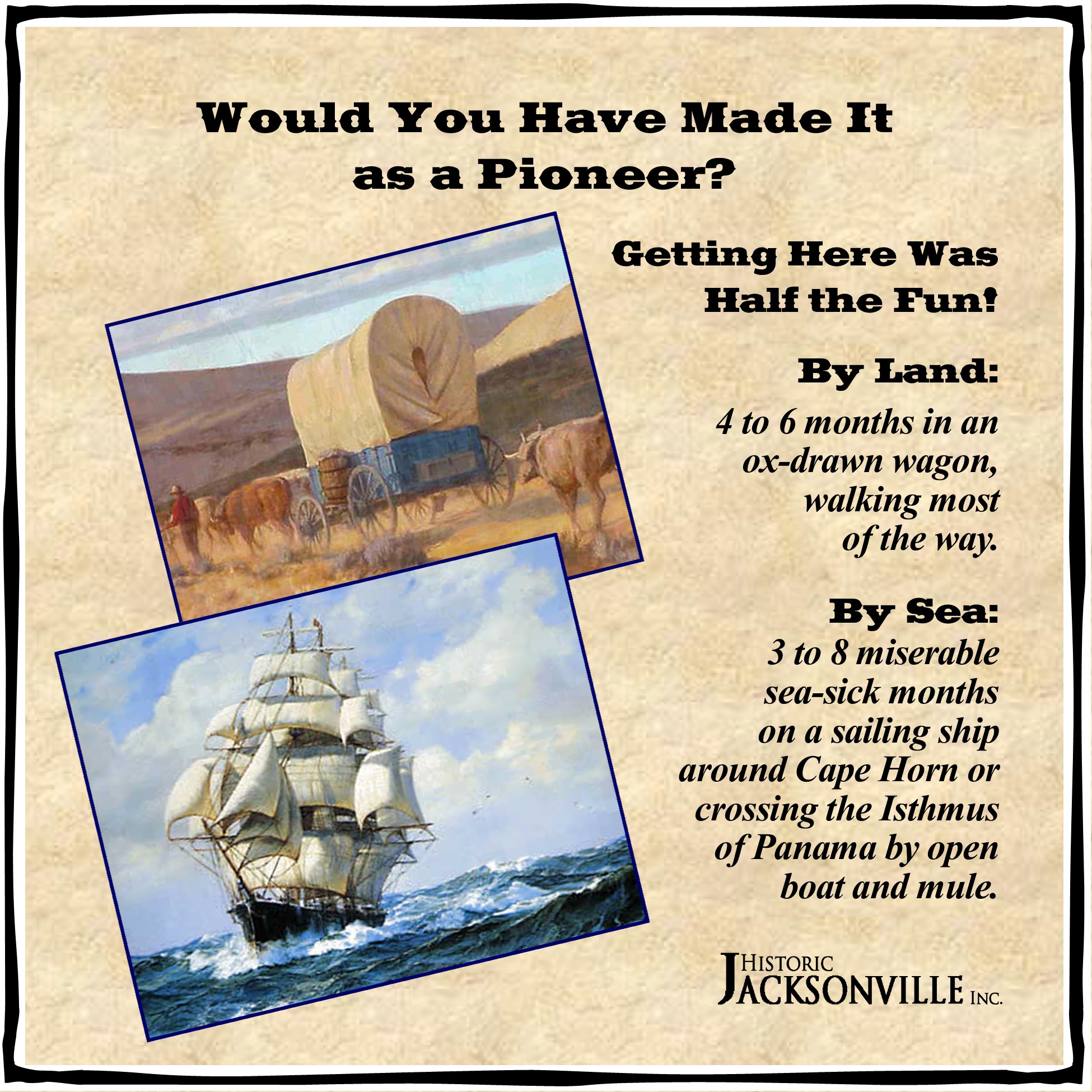

Catalpa Tree

For years, 2 huge Catalpa trees with their large heart-shaped leaves and popcorn-like clusters of flowers were prominent features in the yard of Jacksonville’s historic 1873 Beekman House Museum. These quick-growing trees were popular plantings in pioneer settlements throughout the West.

Also known as the Indian bean tree, the Catalpa was valued for its medicinal uses. Tea brewed from its bark was used as an antiseptic to treat snake bites and whooping cough. A light sedative could be made from the flowers and seed pods, and the flowers were used for treating asthma. The leaves could also be turned into a poultice for treating wounds.

However, the leaves may have served an even more valued purpose. Prior to the days of indoor plumbing, the large, soft Catalpa leaves may have been a welcome alternative to the Sears Roebuck catalog….

You can appreciate the remaining 100-year-old Catalpa tree whenever you visit the Beekman House Museum – although public restrooms have now replaced the 2-seater outhouse which you can still see in the backyard! For information on Historic Jacksonville’s Beekman House tours, visit www.historicjacksonville.org.

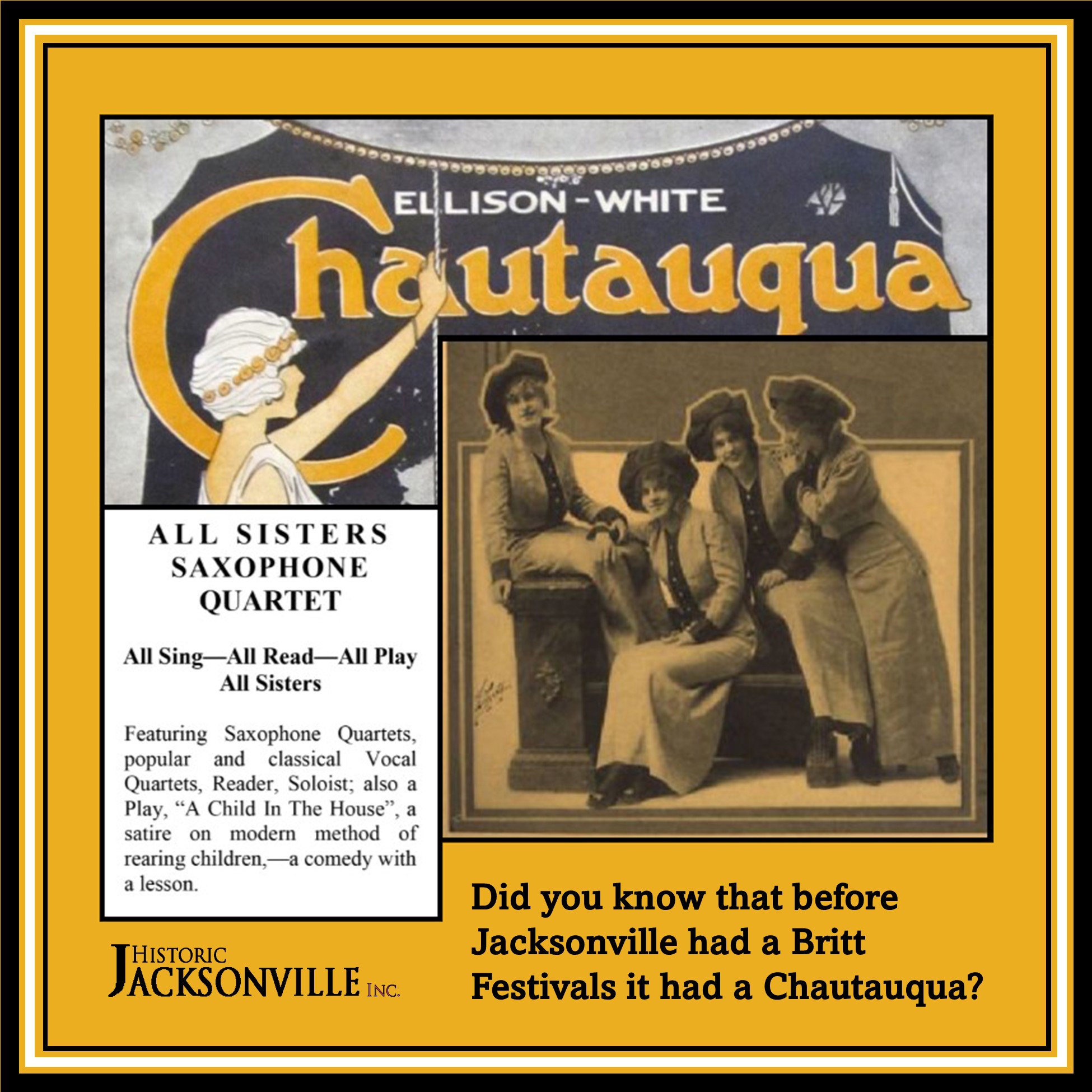

Chautauqua

Did you know that before Jacksonville had a Britt Festivals, it had a Chautauqua?

Chautauqua was a highly popular adult education movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that brought speakers, teachers, musicians, showmen, and preachers to cities and rural communities. President Theodore Roosevelt described Chautauqua as “the most American thing in America.”

In 1924 and 1925, an inspired Jacksonville City Council persuaded enough backers to secure a week of entertainment from the Ellison-White Chautauqua Company. Lacking a grand auditorium or park, Jacksonville’s first season was held in the high school gymnasium; the second in the U.S. Hotel ballroom. Season tickets sold for $2, enough to secure “wholesome college-type entertainers who presented genteel program material.”

One of the highlights of the first season was the Rouse “All Sisters Quartet,” 4 saxophone-playing sisters from Iowa. Regrettably, both seasons ended in a deficit. Medford was campaigning to become the county seat, Jacksonville was becoming a backwater, and citizens had become more concerned with necessities than culture. But for this brief period in the 1920s, Jacksonville still enjoyed a touch of glamor!

Chinatown

Jacksonville was home to the first Chinatown in Oregon, located along West Main in the area where Gogi’s, Elan Guest Suites, and Veterans Park are now to be found. This area was the town’s original commercial center, but as businesses relocated to California Street in the 1850s, this block became home to hundreds of Chinese workers brought here by labor bosses to work the gold mines. As the gold played out, the Chinese Quarter was gradually abandoned. In 1888, most of what were by then derelict buildings burned in one of Jacksonville’s many fires!

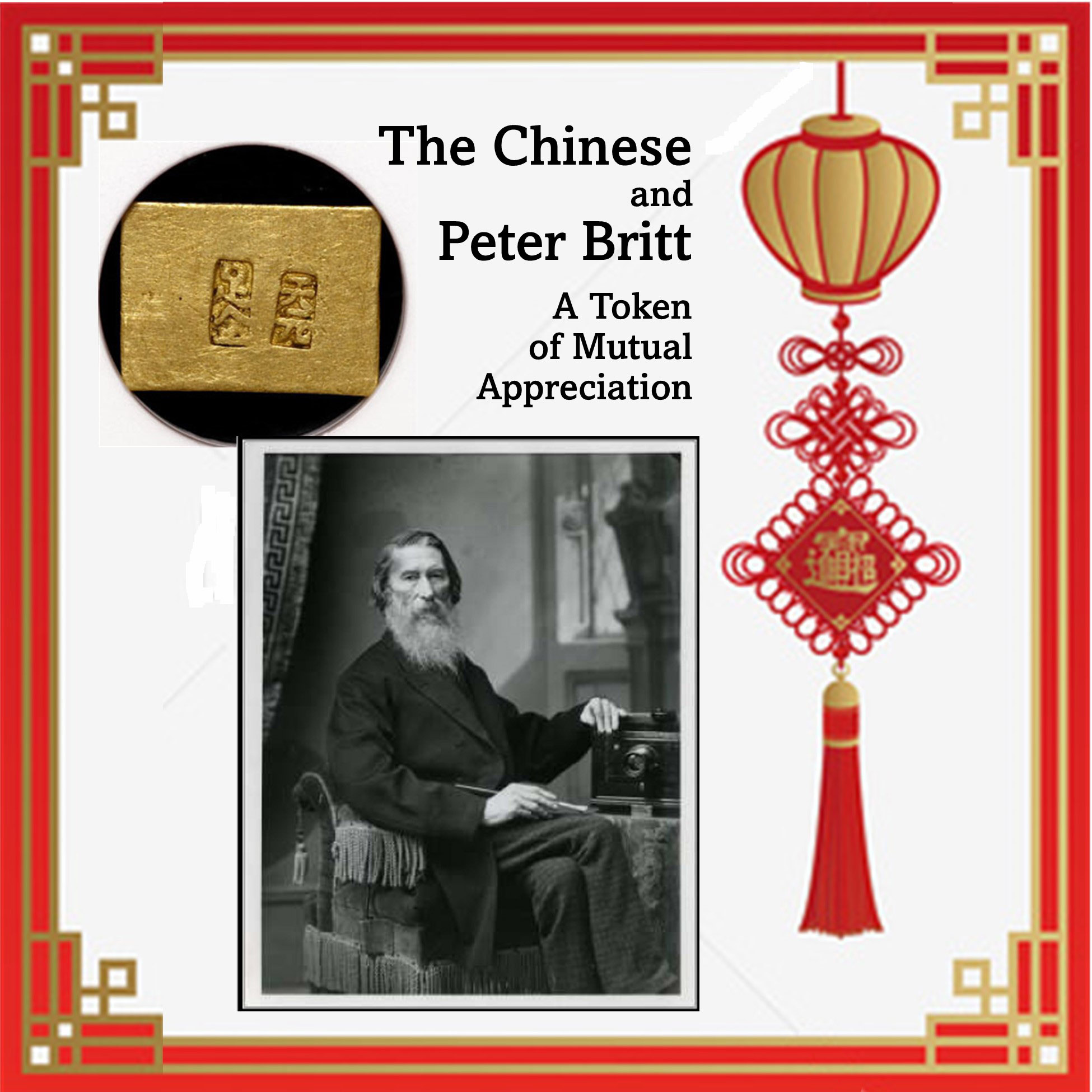

Chinese Gold Ingot

This small gold ingot weighing 2.2 grams was made from gold dug in Jacksonville by Chinese miners who camped on property owned by photographer Peter Britt. At a time when most Westerners treated minorities poorly, Britt was noted for his friendly dealings with the Chinese. The miners refined, cast, and presented the ingot to Britt around 1854. The characters on the front translate as “Heaven Original” and “Sufficient Gold”; the back is blank. At the time coins were in limited supply and most business was done by barter or by payment in gold. This ingot would have been intended for use as money. According to Britt’s son Emil, it was given to his father as a token of appreciation. We would like to think the appreciation was mutual.

This unique piece was the subject of an article by David T. Alexander in the March 1987 issue of “The Numismatist” and its image served as the cover illustration. Alexander summarized its importance: “This Chinese piece exists today with impressive historical evidence documenting that it was, without a doubt, made in Oregon from native gold; dug, refined, and cast by Chinese miners; and presented by them to their friend and benefactor, Peter Britt. As far as is known, the ingot is unique and may be the latest significant addition to the history of pioneer gold.”

Chinese Mining Tunnel

Did you know that when Jacksonville’s current Library was built with funds from a 2000 bond issue, construction workers discovered a large tunnel that ran under Highway 238 and into the lower Britt Gardens?

It seems that undermining Jacksonville may have been a common practice long before the Great Depression of the 1930s. According to A.C. Van Gelder, an old-time miner and prospector, Chinese miners dug an extensive tunnel under much of Jacksonville in the late 1800s. In 1968, Van Gelder considered opening the “Chinese Tunnel” as a tourist attraction since it ran under much of his property.

The tunnel began near the bridge west of Jacksonville on what is now Highway 238, passed under the old train depot (now the Visitors Center), ran across Oregon on the south side of C Street, and followed the “rim” of C Street almost to 4th, ending under the community center (now the Jacksonville Inn parking lot).

The Chinese miners had dug down 12 feet to bedrock to create the tunnel. They had also used timbers to shore up the “drift” so the tunnel would not cave in, apparently an unusual practice for them. In 1968, the tunnel had caved in only one place since its excavation—at the southeast corner of C and North Oregon streets.

This is most likely the same tunnel under Highway 238 that was discovered when the current Jacksonville Library was built. It could be Chinese, since it originates in an area adjacent to what was Jacksonville’s Chinatown. But it’s equally likely that it dates from the Depression Era since one would think that 19thCentury Jacksonville residents would have been aware of any Chinese miners digging a tunnel under their properties.

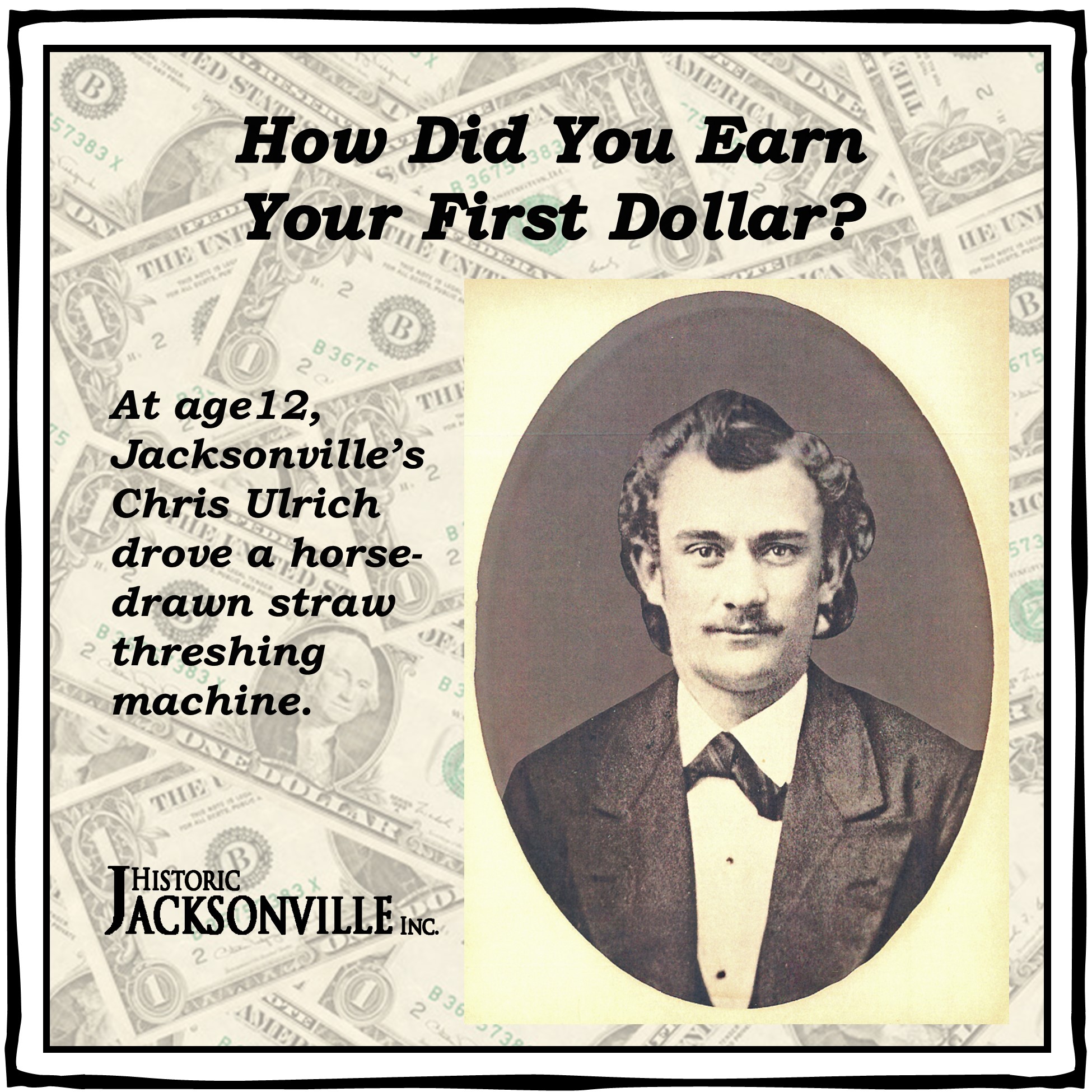

Chris Ulrich

Do you remember how you earned your first dollar? In 1921, Chris Ulrich, variously proprietor of Jacksonville’s New State Saloon, owner of a planning mill and sash and door factory at the corner of California and 5th, then in the feed and flour business, recalled his initial hard-earned buck.

“I worked three days driving a straw horse on a threshing machine for my first dollar. I was about the size of a minute, and all I had to do was work from sunup to sundown, driving an old horse hooked onto a fence rail. I saw I wasn’t going to get rich at this, so I went to work for an Irishman by the name of Fehely. [Fehely was one of Jacksonville’s earliest brick makers.] It was another fine job, the hours being as long as you had strength enough to wiggle. Fehely had a couple of daughters who came right out in the brickyard and worked alongside the boys. They were good looking and good workers.”

Ulrich was probably about 12 years old at the time. Born in Iowa in 1853, he had come west with his parents in the 1860s. By age 19 he had become a carpenter’s apprentice to David Linn, before subsequently becoming saloon keeper, building contractor, and then merchant. Ulrich was also involved in Jacksonville government, serving on the City Council at age 30 and later acting as city street commissioner.

(And yes, we know that in the 1860s Ulrich’s first dollar would have been a gold coin!)

Crater Lake Discovery

In 1853, Prospector John W. Hillman of Table Rock City (Jacksonville) was reportedly the first American of European descent to see Crater Lake—and he nearly fell into it. While with a party of miners seeking the storied “Lost Cabin Gold Mine,” Hillman was riding a mule along a high ridge when the animal lurched to a stop and would not budge. Hillman looked down and saw that the beast had come right to the rim of a huge crater with a brilliant blue lake at its bottom. “Not until my mule stopped within a few feet of the rim of Crater Lake did I look down,” he later wrote, “and if I had been riding a blind mule I firmly believe I would have ridden over the edge to death and destruction.” But with no luck in their quest and provisions exhausted, Hillman and his fellow miners returned to Table Rock City. Although they debated whether to call their find Deep Blue Lake or Mysterious Lake, a lake was of only passing interest when gold was the objective. Deep Blue Lake was forgotten until it was discovered by another party 9 years later.

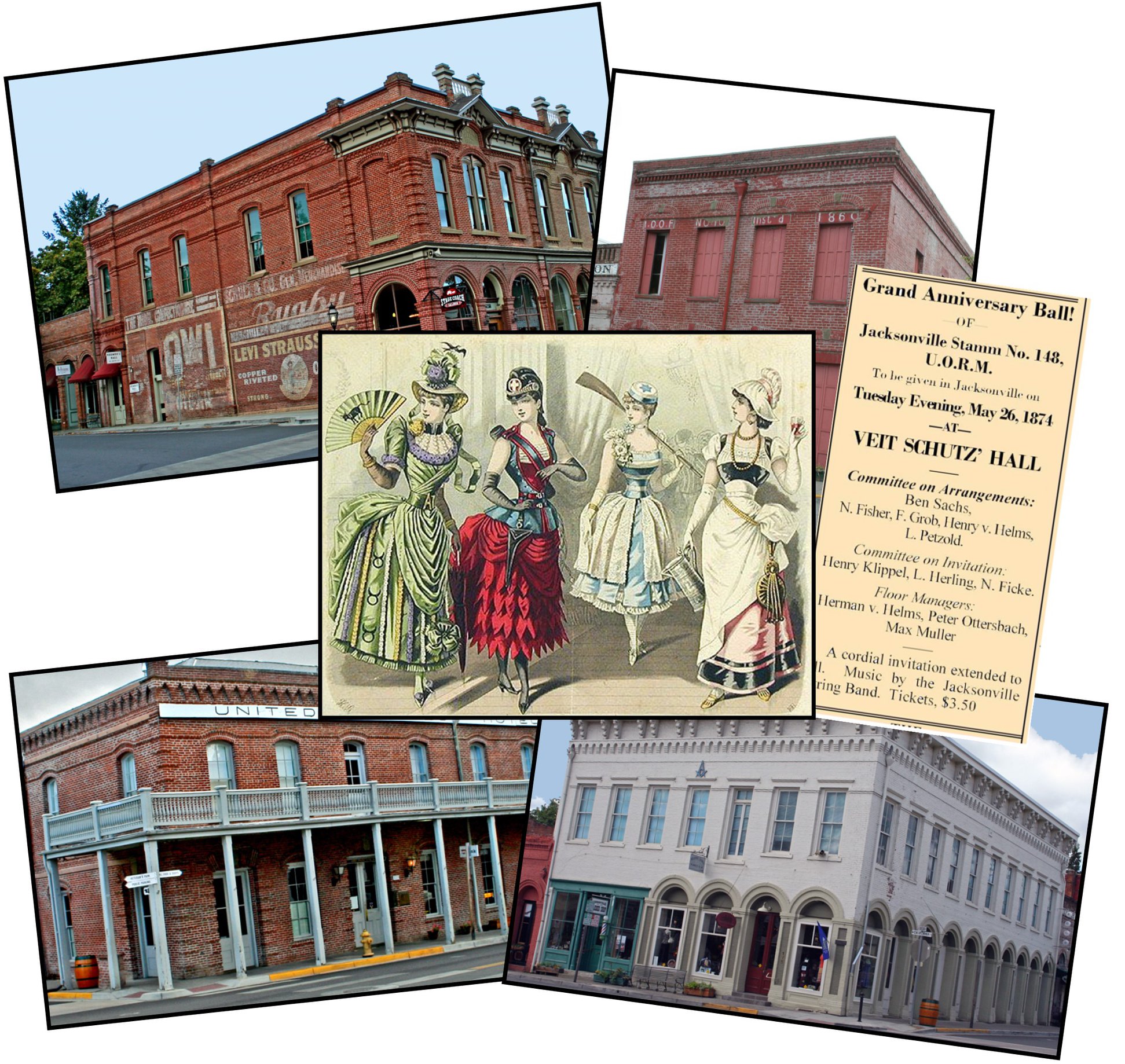

Dances and Fancy Dress Balls

Jacksonville’s Redmen’s Hall, the U.S. Hotel, the Masonic Hall, the Odd Fellows building, and Veit Schutz Hall all had ballrooms or dance floors, and weekly dances were a popular form of local entertainment. Masquerades, or fancy-dress balls, were particularly popular over the holidays. At masquerades, prizes were typically awarded for best costume. And it was also common for spectators to pay to watch the costumed partygoers entering the ball—like fans today paying to watch celebrities attend a gala or awards ceremony today. For Jacksonville’s 1901 New Year’s Eve ball, the local newspaper noted that a Portland costumer came down with trunk loads of costumes that could be rented or purchased for the occasion.

Dr. Brooks & A Flag Pole

Flags and flagpoles have always been an important way of expressing political opinions and “freedom of speech”—perhaps even more so in the 19th Century than now. Historic Jacksonville has previously shared the story of Zany Ganung, who in 1861 returned home to Jacksonville from tending a sick patient only to find that someone had erected a flagpole flying the Confederate “palmetto and rattleshake flag” across the street from her front door. Without a word to anyone, Zany entered her California Street house, returned with a hatchet, crossed the street, chopped the pole down, and used the flag to stoke her stove. However, Zany had a precedent. In 1855, when town women protested their men folk leaving them unprotected during the Indian Wars, local “wags” ridiculed them by hoisting a petticoat at half mast on the post office flagpole. The women were greatly incensed but had no means of getting the petticoat down. Dr. Charles B. Brooks, a local physician, saved the day for the feminine part of the population by hauling it down, thus allowing the women to march off in triumph.

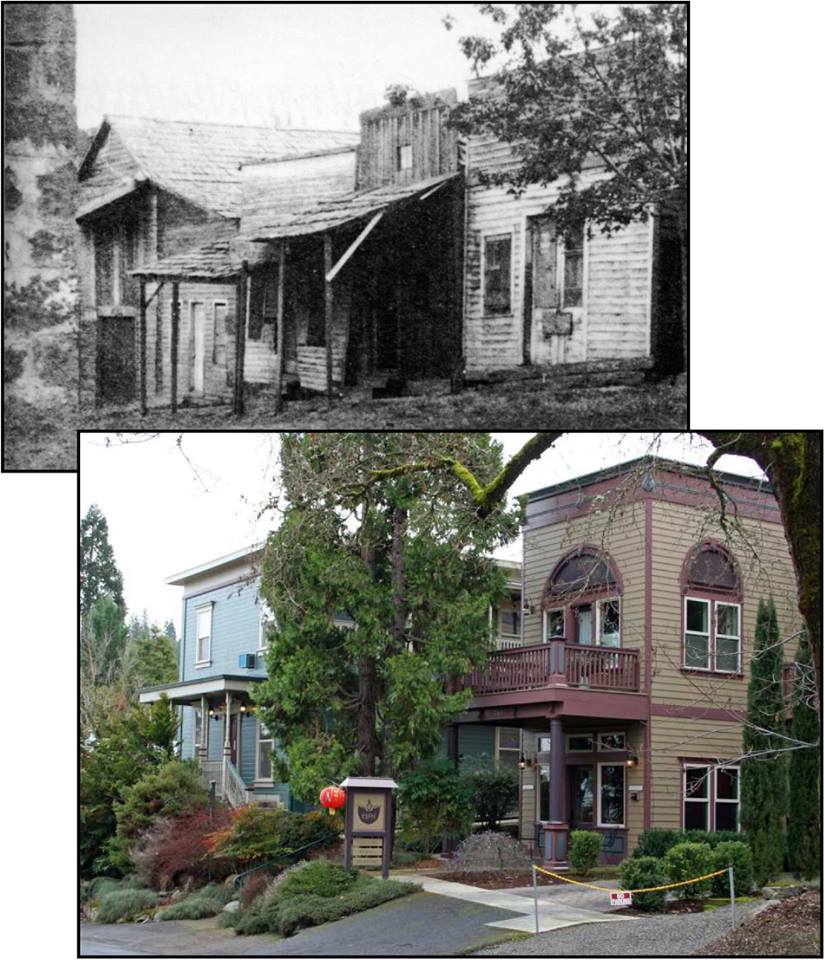

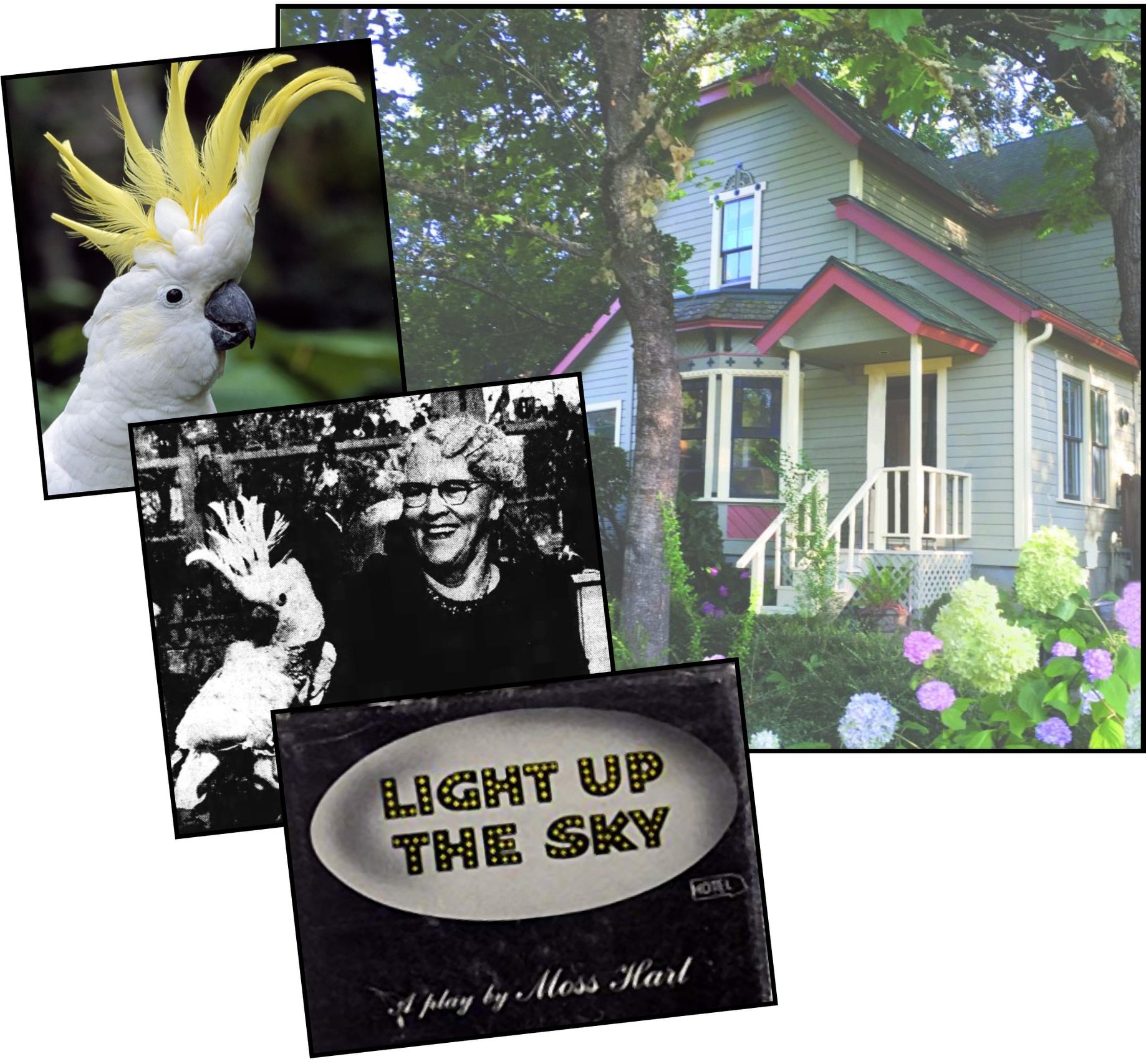

Early Newspapers

Early Jacksonville had a succession of newspapers over the years, many of them competing and espousing opposing political viewpoints. When the Democratic News plant was destroyed in the fire of 1872, it rose again as the Democratic Times. Initially housed in the Orth Building on South Oregon Street, the Times soon outgrew that space and established its own offices at the corner of C and North 3rd streets. The Times lasted into the early 1900s when it merged with the Southern Oregonian. Depression era miners of the 1930s uncovered the Times doorstep as they undermined almost every inch of Jacksonville. The current private residence was built as a rental property in the 1930s over one of these old mine shafts.

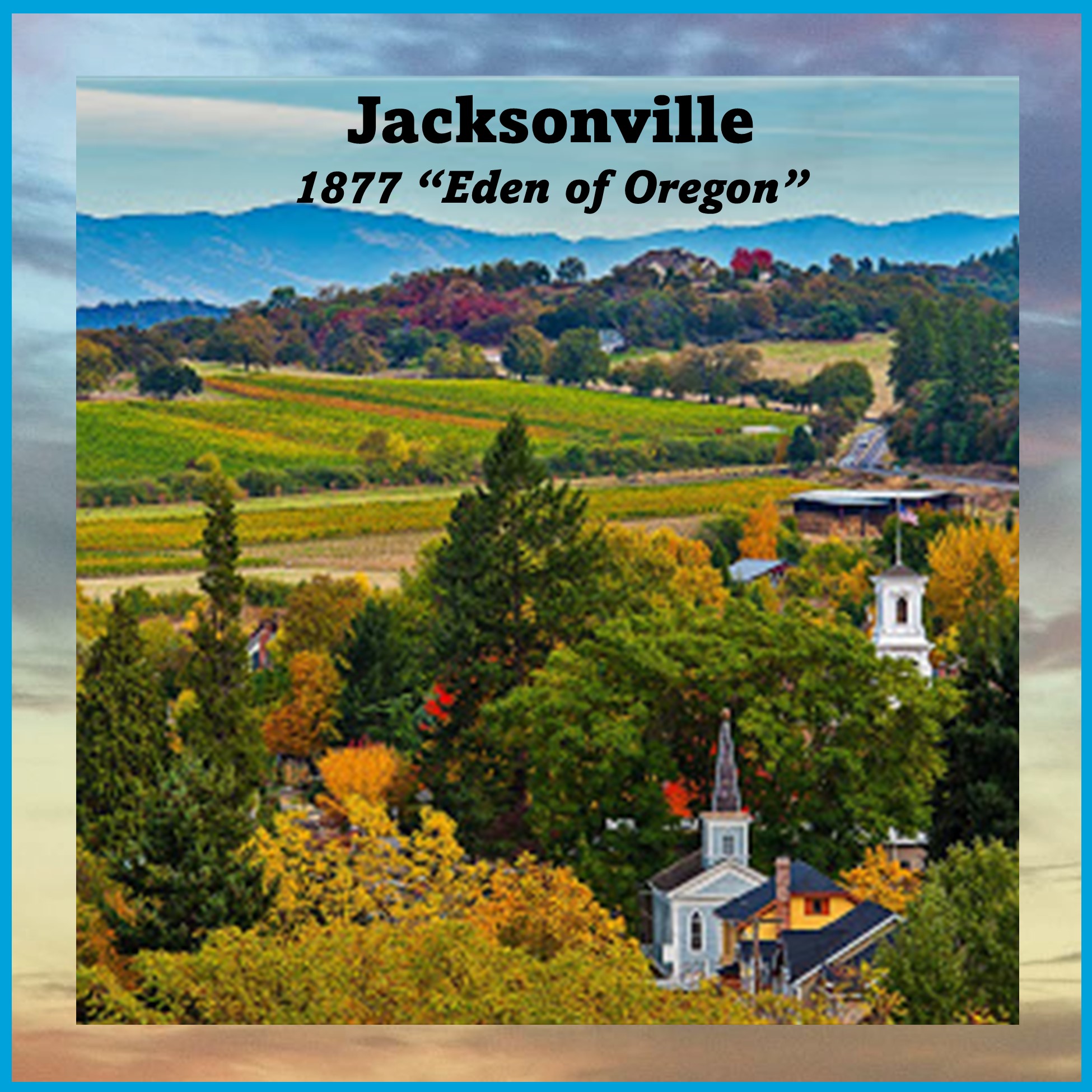

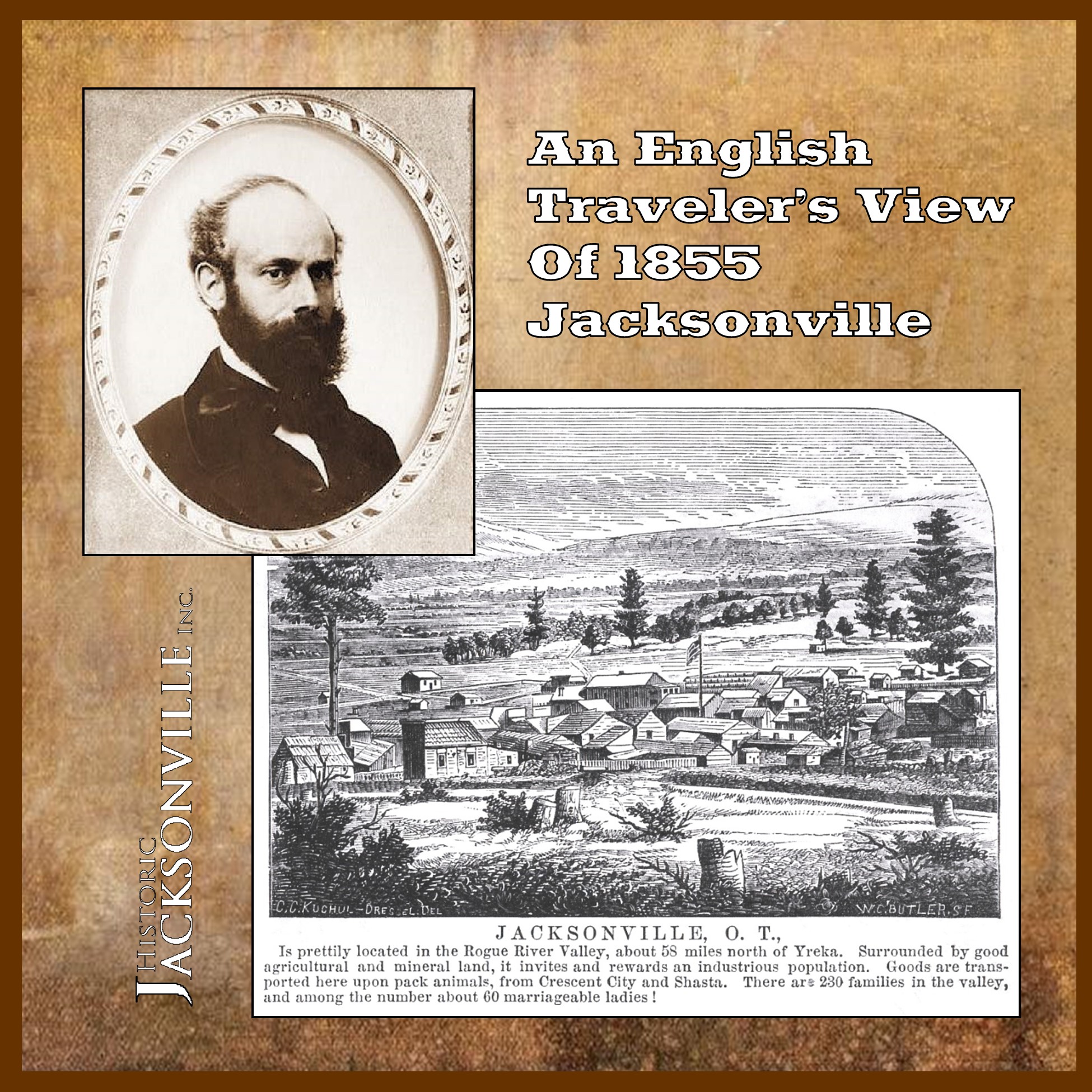

Eden of Oregon

We know that Jacksonville is a special place, a fact that has been recognized for a long time. As early as 1877, the publisher of Portland’s “West Shore” magazine described Jacksonville and the Valley as THE EDEN OF OREGON. He wrote: During a visit to Southern Oregon, on the 15th of July we observed in the gardens of Peter Britt, at Jacksonville, some magnificent fig trees. They were in full bearing, and the fruit was just turning ripe, whilst the second crop was commencing to form. A very excellent article of grapes also grows in this county, and at Mr. Britt’s place we tasted a one-year-old claret of his own growth and manufacture; and we very much doubt if it can be surpassed in the much boasted-of California vineyards. All the grain and fruits known to the tropics grow here to perfection. Extend the Oregon & California Railroad to Jackson County, and she is capable of supporting the entire present population of Oregon.

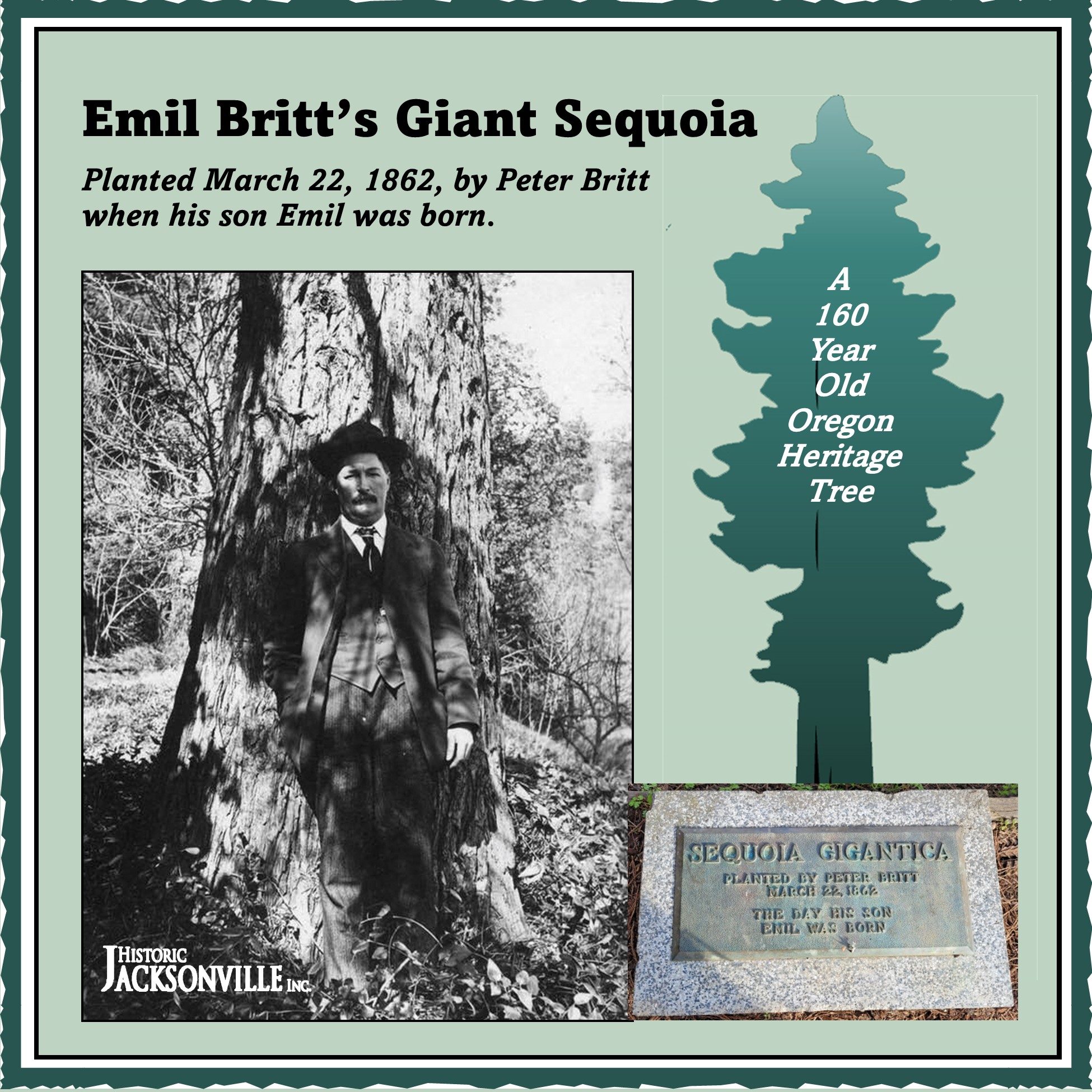

Emil Britt’s Giant Sequoia

Have you ever pondered the Giant Sequoia that marks the Jacksonville Woodlands Sarah Zigler trail head? Giant Sequoias are not native to this area, so how did it get there?

All of this acreage was originally part of Britt’s donation land claim, and as you know, Peter Britt was not only a photographer but also a horticulturalist. He planted this tree as a seedling on the day his first son, Emil, was born—March 22, 1862. That’s Emil standing in front of the tree. The photo may have been taken by Peter Britt himself in the late 1890s.

This majestic Giant Sequoia is now 160 years old! Standing 200+ foot tall, it’s an official Oregon Heritage Tree. The next time you head up to the Britt Gardens, take a few minutes to walk out to the Zigler trail head and the Britt Sequoia and admire this symbol of history, vision, and endurance.

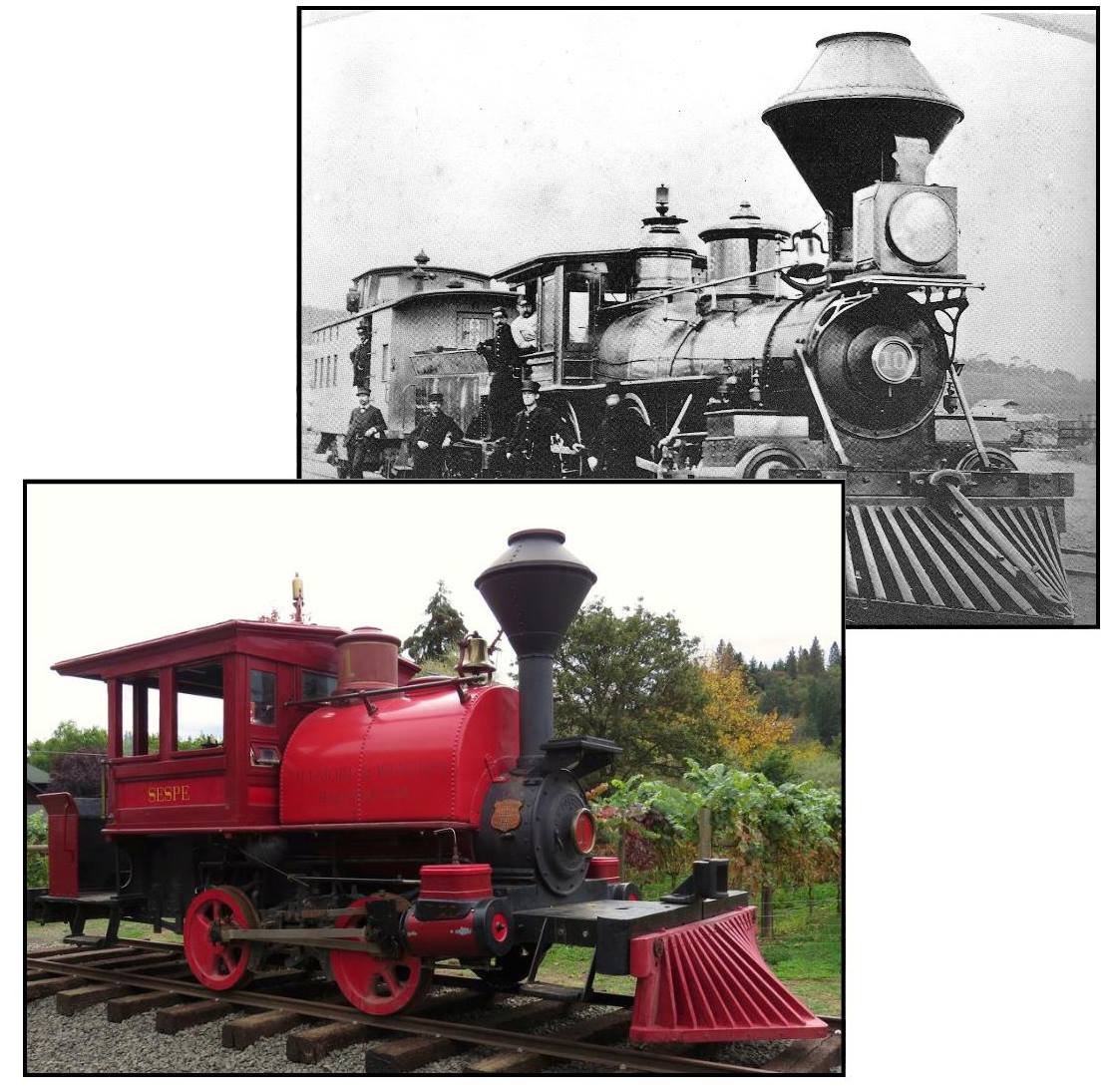

Engine #1

The Rogue River Valley Railway, which operated from 1891 until 1925, was Jacksonville’s attempt to maintain regional economic supremacy after the main Oregon & California/Southern Pacific railroad line by-passed the town in favor of the flat valley floor. The RRVR hauled gravel, bricks, timber, crops, livestock, mail and passengers over a 5-mile, single track spur line that connected Jacksonville with Medford. The Railway’s first steam engine, Engine # 1—fondly called the “Tea Kettle” and the “Peanut Roaster”—proved underpowered to haul heavier freight loads up the 3% grade from Medford. It was soon replaced by larger engines like the one shown. Engine #1 was relegated to passenger service, pulling a single Pullman car. In 2014, Mel and Brooke Ashland arranged for the purchase and restoration of Engine #1. It now sits on original track on the Bigham Knoll Campus at the end of East E Street.

Fire Engine Company #1

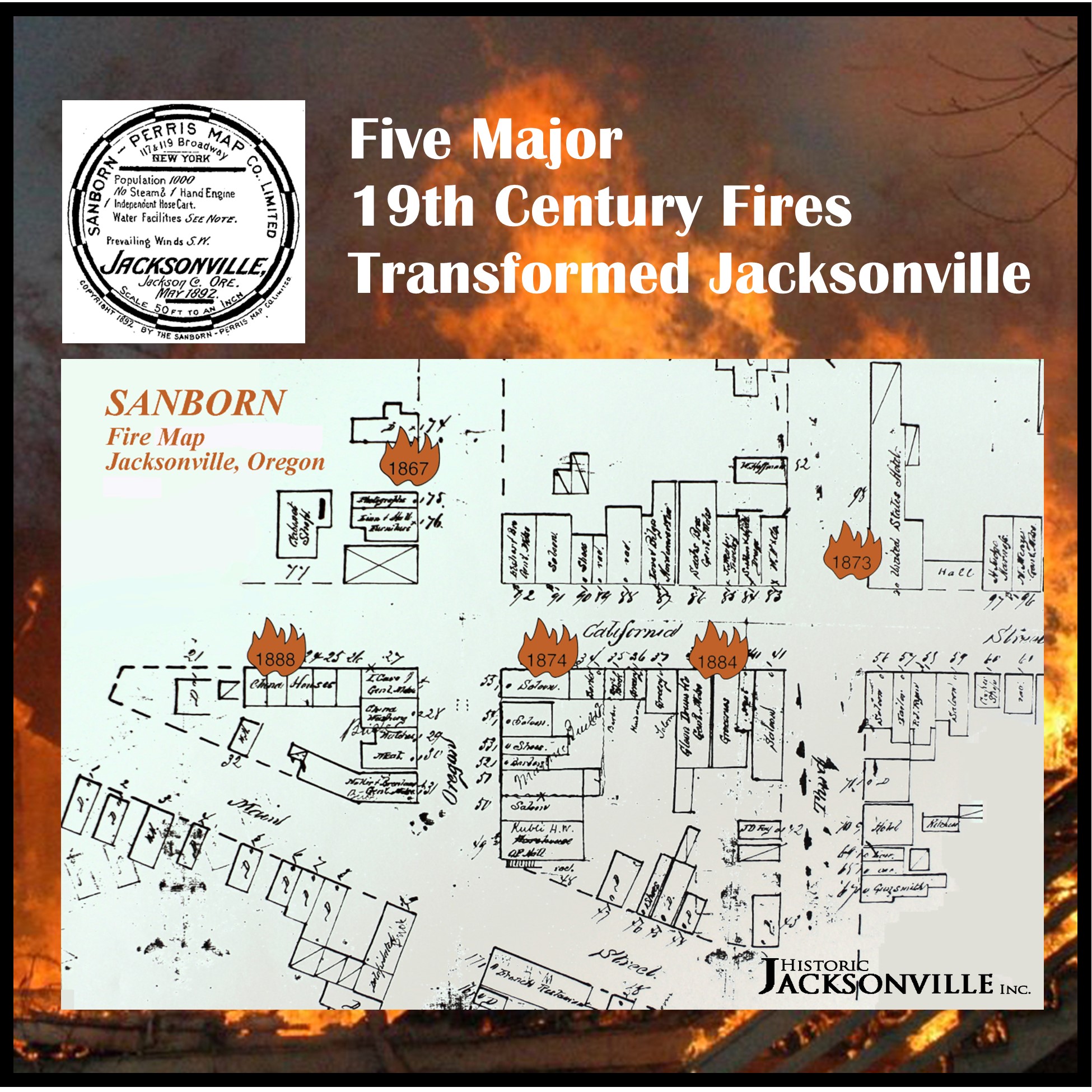

Fire was a significant hazard in early Jacksonville with major fires destroying portions of the town in 1867, 1873, 1874, and 1884, and 1888. The town’s volunteer fire department, Engine Company #1, responded to the call of the Applebaker Fire Hall bell well into the 1950s. Today, Engine Company #1 provides back up services to the town’s professional fire fighters, and the Applebaker Fire Hall, attached to Old City Hall on South Oregon Street, houses an historical fire museum.

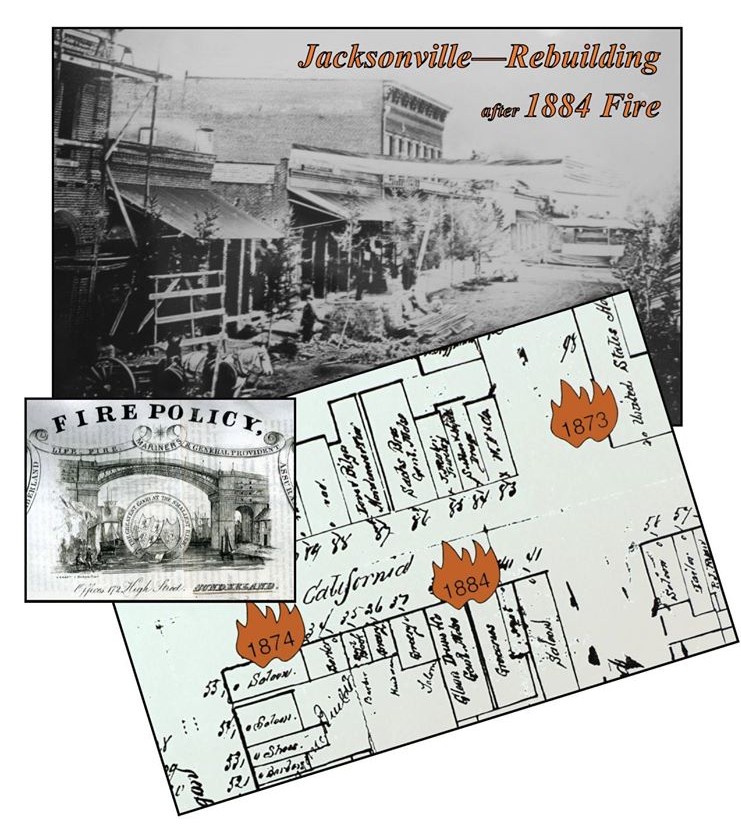

Fire of 1884

Fire was a significant hazard in early Jacksonville with major fires destroying portions of the town in 1867, 1873, 1874, and 1884, and 1888. The town’s volunteer fire department, Engine Company #1, responded to the call of the Applebaker Fire Hall bell well into the 1950s. Today, Engine Company #1 provides back up services to the town’s professional fire fighters, and the Applebaker Fire Hall, attached to Old City Hall on South Oregon Street, houses an historical fire museum.

With major fires destroying portions of early Jacksonville, Oregon, fire, or more accurately “fire insurance” was the impetus for most of the brick construction that now comprises the town’s historic commercial district. The City Fathers did not mandate brick commercial buildings until 1878. However, very early on, insurance companies penalized owners of wooden structures—and buildings adjacent to wooden structures!

Fires

Major 19th Century fires shaped historic Jacksonville as we know it today. An 1867 kiln fire that began at David Linn’s lumber mill at the corner of California and S. Oregon also destroyed neighboring residences. With only a bucket brigade and a hook and ladder wagon, Jacksonville’s Engine Company No. 1 could do little more than watch.

In 1873, a volunteer bucket brigade was outmatched by a fire at the first U.S. Hotel. Within 15 minutes it did $50,000 in damage (equivalent to $1 million today) at a time when few had fire insurance.

In the first week of July 1874, two blocks at the southeast corner of California and Oregon went up in flames, destroying many of the town’s original wooden buildings including the notorious El Dorado Saloon. Again, the bucket brigade could only watch and help salvage items from the stores.

In December 1984, a New Year’s Eve fire that began at the New State Saloon at the corner of California and 3rd streets (now the location of Redmen’s Hall) wiped out a block of businesses, the post office, and 2 homes. By this time Engine Co. No. 1 had a pump wagon, but an inexperienced volunteer forgot to attach a filter.

In September 1888, fire again engulfed David Linn’s business at the corner of California and Oregon streets, destroying not only his furniture store and planning mill, but also wiping out most of Jacksonville’s original Main Street business district which had become the 1st Chinatown in Oregon.

Although the 1899 Jackson County Jail fire is not considered a major fire, 3 inmates who were lodged in the jail when it burned on July 12th died in the blaze that destroyed the county’s 2nd jail building on this site. One prisoner was due for release the next day. The sheriff was supposed to have been spending the night in the jail, but 2 different versions of his “whereabouts” have him either in a local saloon or enjoying the attractions of a local hotel that accommodated a gentleman’s “needs.”

We owe a huge debt of thanks to our current fire department—along with prayers for them and other firefighters battling to keep us safe this season!

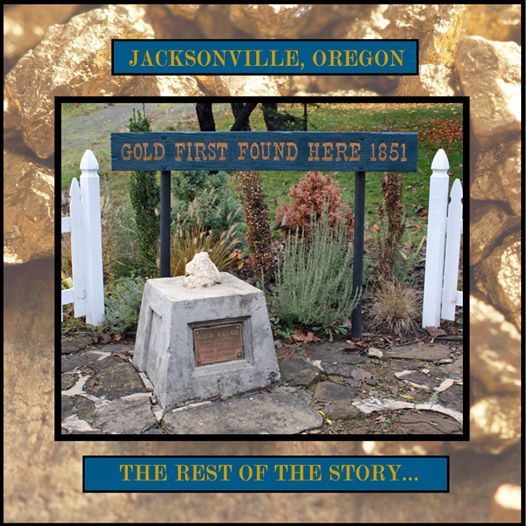

First Gold Found Here #1

Of all the Jacksonville, Oregon “firsts,” the question of who first found gold may be the most debatable. The “Gold First Found Here” marker on Applegate Street where it crosses Daisy Creek would have you believe that James Clugage and James Pool, two packers carrying goods to the mining camps in California, did a little panning in the creek in the winter of 1851-52 and found the first “color.”

But the story is a little more complex than the marker would have you believe. Several gold discoveries had been made in the Illinois Valley at Josephine and Canyon creeks and Sailor’s Diggings in 1851 before the first Rogue River Indian War broke out.

And the previous fall, the son of Alonzo Skinner, the local Indian agent, and one of his employees, a Mr. Sykes, had found gold in nearby Jackson Creek. Clugage and Pool learned of their discovery when they spent a night at the Skinner homestead. So, before heading to Yreka, Clugage and Pool took time to pan a little and, voila!

Clugage and Pool hightailed it south and immediately filed land claims on what is now most of Jacksonville. They returned and spent the next few weeks mining, but then Clugage did something unheard of—he publicized his “find,” even boasting to California newspapers of taking out 70 ounces of gold a day from his claim. Thousands of miners poured over the Siskiyous into the Valley, closely followed by merchants, gamblers, courtesans, and settlers—all needing a mining, business, or home site.

In the case of Jacksonville’s gold discovery, the honor of “first” probably belongs to Skinner and Sykes. But Clugage may have found the mother lode—he made a fortune selling land!

First Gold Found Here #2

Have you hiked Rich Gulch Trail in the Jacksonville Woodlands? The trail may have seen its share of riches, but Historic Jacksonville, Inc. has discovered that it may not have been the site of the “mother lode” when it came to local gold strikes.

In January of 1867, a major storm brought so much rain that Jackson Creek flooded much of the town, washing out mining claims in the Woodlands area and flooding businesses and homes. “The Oregon Sentinel” newspaper reported on much of the damage:

“In town, the first building attacked was Plymale’s Livery Stable. The water was high enough to run around the building on the side fronting “C” Street. Great fears entertained that the waters would break through in the old drift or tunnel running down “C” Street, in which case the whole creek would probably have cut a channel, DISCHARGING INTO RICH GULCH AT THE CLERK’S OFFICE.”

Remember that old mining tunnel we described in a previous post? It ran from the lower Britt Gardens, under what is now Highway 238, behind the post office and Visitors Center and down C Street almost as far as the Jacksonville Inn parking lot and North 4th.

Although the exact location of the 1867 County Clerk’s office is unknown, it would have been close to the seat of county government. This January 26, 1867, newspaper account would seem to place Rich Gulch in the vicinity of what is now Jacksonville’s “Courthouse Square” and New City Hall. And that area was “off limits” for 1930s mining permits and undermining activities. Hmmm….

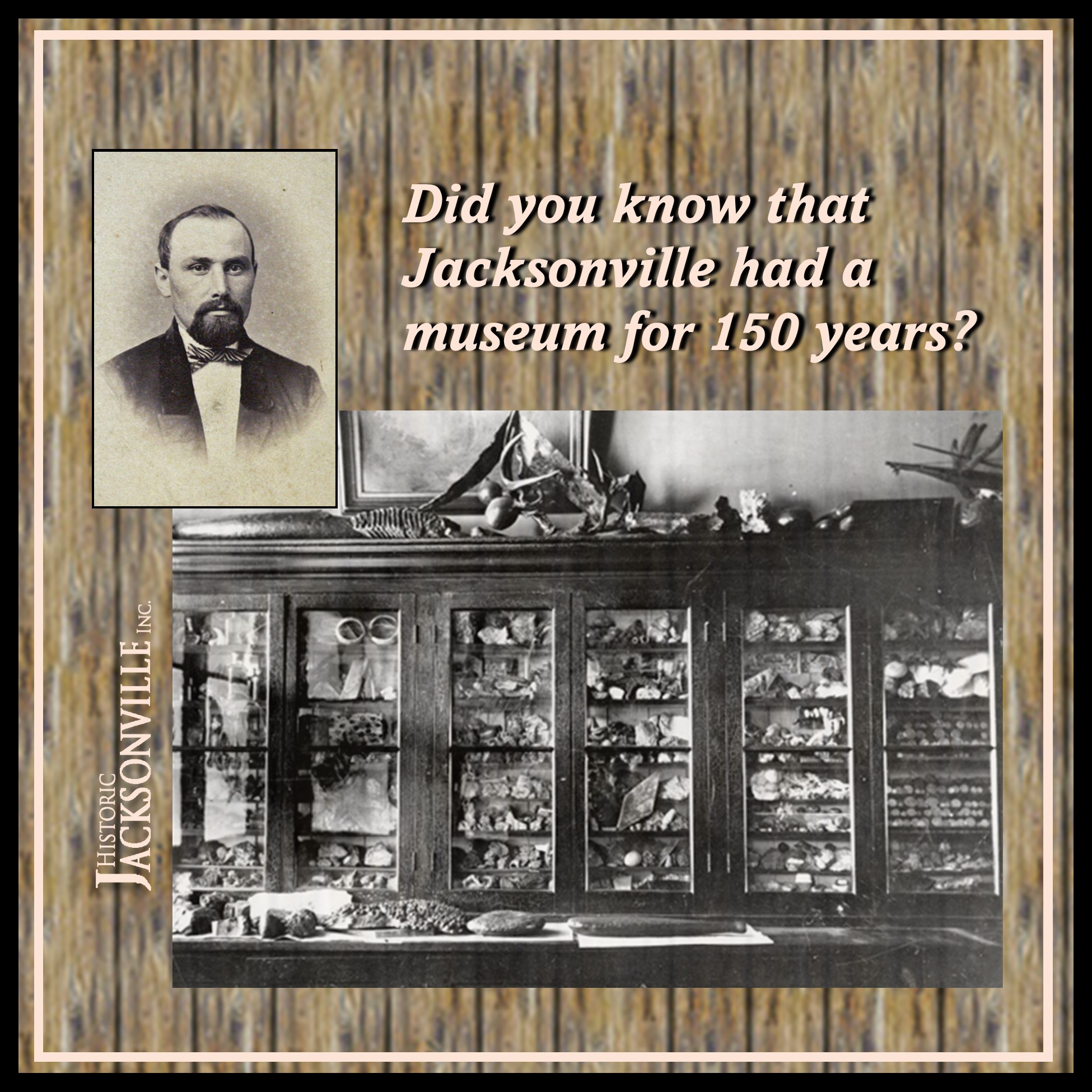

First Museum

Since a new Jacksonville Museum is much in the news today, Historic Jacksonville, Inc. thought we would remind residents that a museum was a Jacksonville institution for 150 years from 1860 to 2010! Residents fondly recall visiting the last Jacksonville Museum and visitors regularly ask the Visitor Information Center’s staff, “Where’s the museum?”

The town’s first museum was housed in the Table Rock Billiard Saloon, constructed in 1860 at 165 S. Oregon Street. Saloonkeeper Herman Von Helms collected fossils and oddities to attract a clientele that then stayed for his lager. When the saloon closed in 1914, the Helms’ “Cabinet of Curiosities” boasted a collection of artifacts valued at $50,000. It encompassed “every possible manner of relic…mutely telling pages in the early history of Jackson County.” Highlights included the first piece of gold found in Jacksonville, a photo and piece of rope from a hanging, and the first billiard table in the Oregon Territory.

Subsequent museums were housed in the Brunner Building, the Bella Union Saloon, the U.S. Hotel, and what is now Jacksonville’s New City Hall. The current Jacksonville Museum proposal would include all of these sites, recognizing that the town itself is a museum—one easily accessed virtually today through apps that will allow visitors to explore specific themes or create their own tours with information about the buildings, the people, and their stories. Old City Hall, the oldest government building in Oregon that remained in continuous use, would be the starting point for sharing Jacksonville and its National Historic Landmark District with the public.

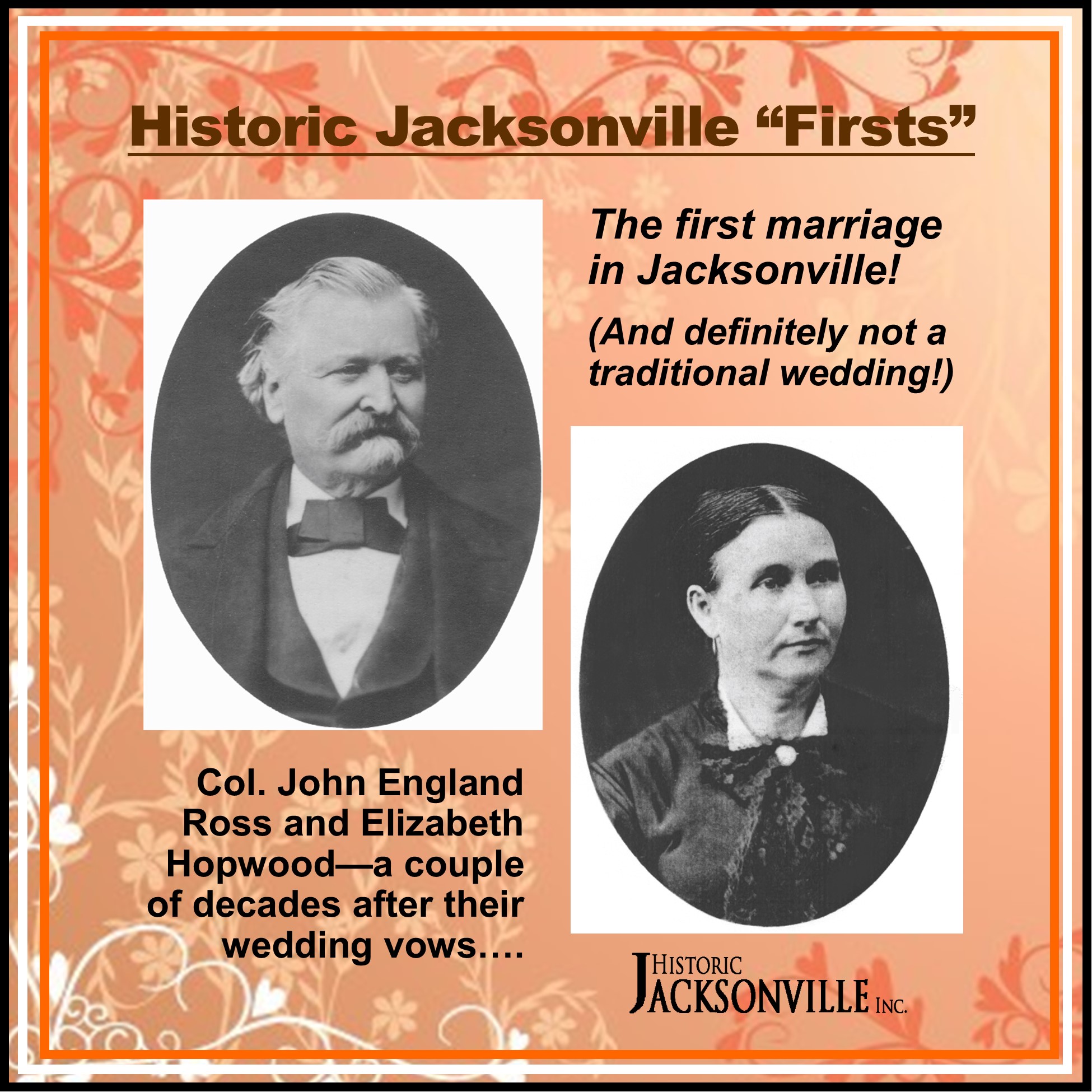

First Wedding in Jacksonville

In January 1853, Col. John England Ross and Elizabeth Hopwood were married—the second wedding in Jackson County and the first in Jacksonville. Naturally, all the town folk were invited. Elizabeth had a special wedding dress made for the ceremony, but Ross had nothing but his buckskins. The ladies of Jacksonville fretted over this lack of proper wedding attire.

Jane McCully offered Ross a white shirt that belonged to her husband, but Dr. McCully’s smaller stature meant the fit was strained at best. When the nervous bridegroom joined a jumping contest with some of the men attending the ceremony, Ross’s exuberance split the shirt down the back. Jane quickly poked holes down each side of the split, laced it together with string, and the wedding proceeded as planned.

With no church and no place large enough to accommodate everyone, Ross and Elizabeth were married on the corner of Main and Oregon next to the town pump, even though it was early January. The Methodist preacher, Reverend Gilbert, presided. The groom was 35; the bride, 18.

The occasion was obvious cause for a jubilee. A progressive supper went house to house, ending with a spectacular wedding cake improvised from duck eggs, brown sugar, and bear suet. A grand ball, probably at one of the local saloons, capped the evening.

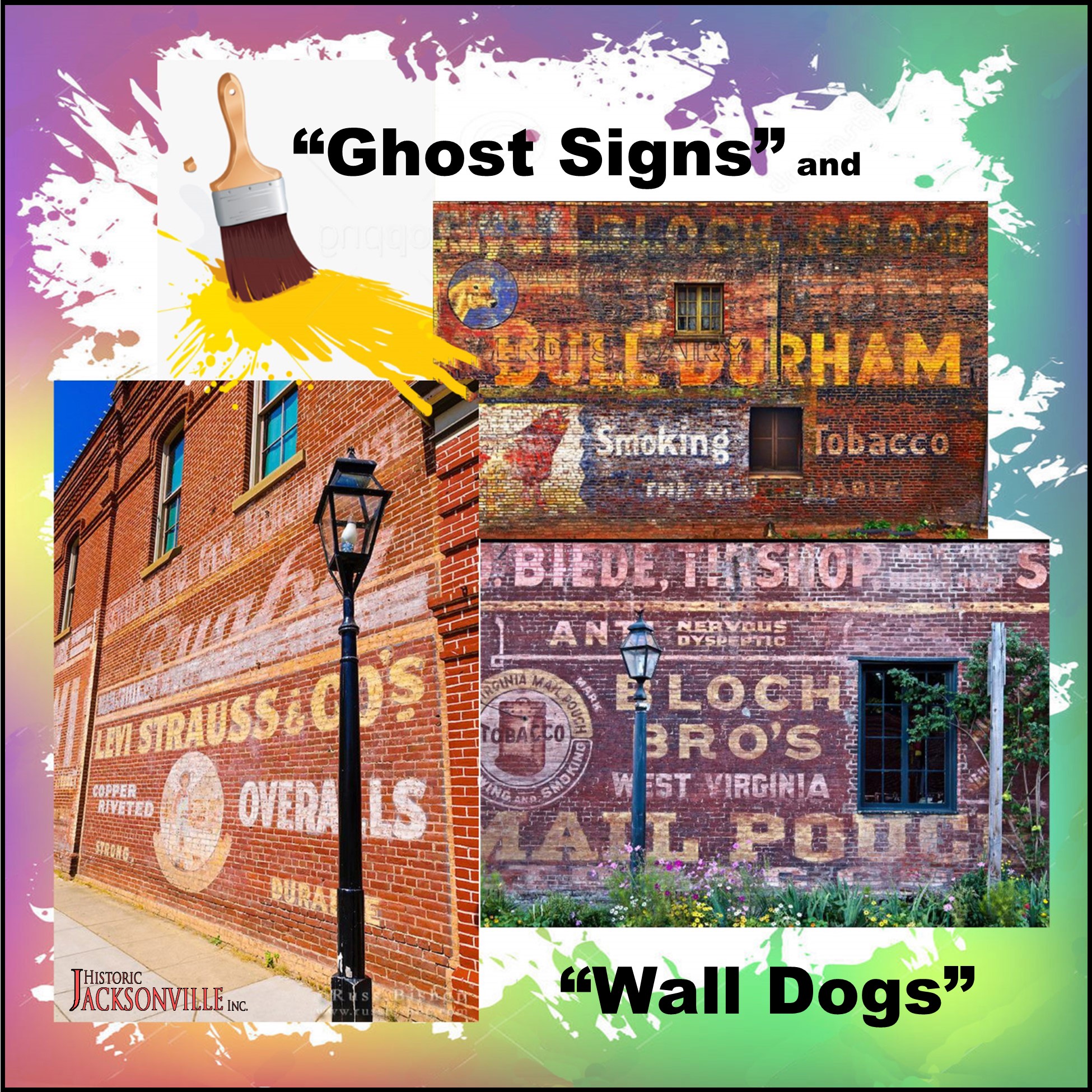

Ghost Signs

In the late 1800s Jacksonville was the hub of Southern Oregon’s commerce and government. During this “exuberant period of American capitalism,” some of Jacksonville’s brick buildings also doubled as billboards featuring large painted signs promoting local businesses. When ownership changed, a new sign might be painted over an old one. These historic brick business ads, known as “ghost signs, were painted by “wall dogs.” Wall dogs, who were usually itinerant sign painters, were a unique combination of muralist and rock climber. Their designs and execution were done by hand while the painter hung from the side of the building. They were called wall dogs because they worked like dogs and they needed to be tethered, or leashed, to the wall. Each wall dog typically mixed his own paint formula, but all formulas contained large quantities of lead—the element that made wall dog careers short lived but ensured the survival of these ghost signs to this day.

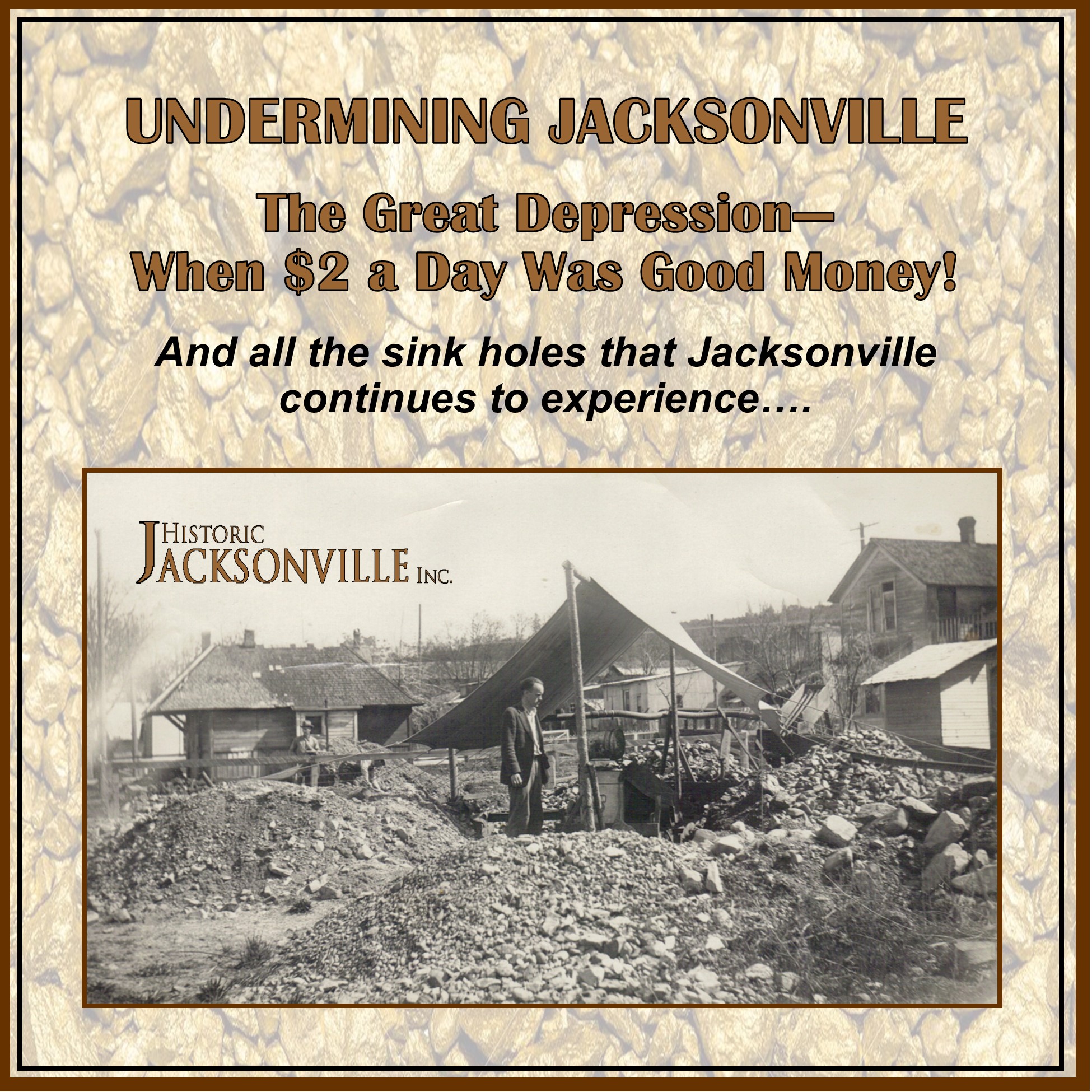

Gold Rush #2, Depression Era Mining

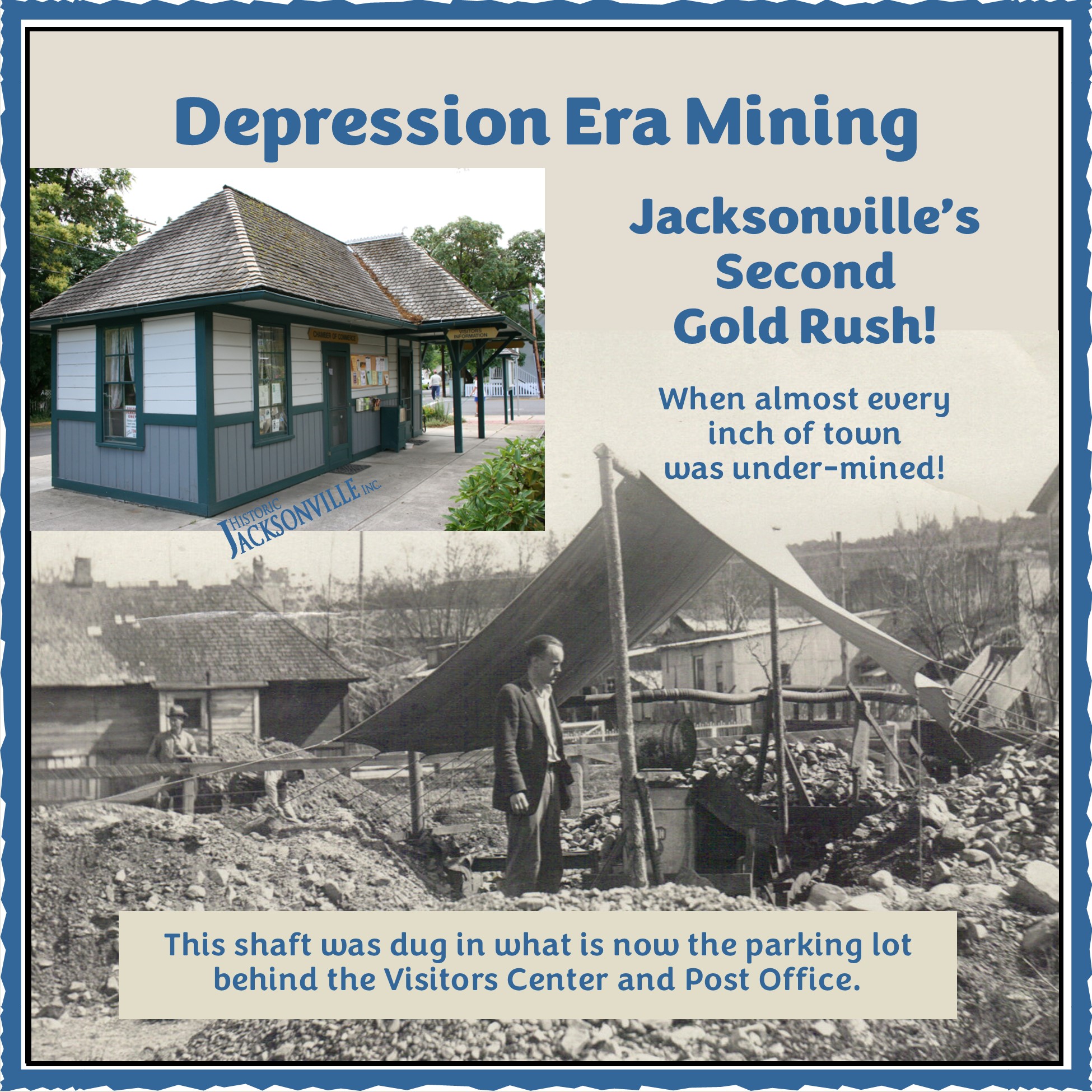

You may be familiar with how the discovery of gold during the winter of 1851-52 led to the founding of Jacksonville. Within a few months the area was dotted with the tents of 3,000+ miners seeking the promise of treasure.

However, you may be less familiar with Jacksonville’s second gold rush. As an alternative to putting residents on the “dole” during the 1930s, the County gave out mining permits, allowing residents to dig for any residual gold lingering from the 1850s. Some got lucky, but most latter-day miners only found enough gold to live from day to day. Still $2 a day was more than most jobs paid—assuming you could find one.

Most mining shafts were dug in backyards, but some residents had sufficient moxie to burrow under the town’s commercial buildings. According to 1935 newspaper accounts, 4th Street had several dips in it; on Main Street, “the bottom fell away from light poles, leaving them suspended by the wires on the cross arms.” The shaft pictured here is in what is now the parking lot behind Jacksonville’s post office and Visitors Center, the old Rogue River Valley Railroad station.

Almost every inch of Jacksonville was “undermined.” The result is periodic “sink holes” opening over old mine shafts around town. In just the past few years we’ve had sink holes opening behind the Jacksonville Inn, in the post office/Visitors Center parking lot, and in Ray’s Market’s parking lot—all remnants of what individuals might do for what one journalist described as a “ham-and-eggs” existence.

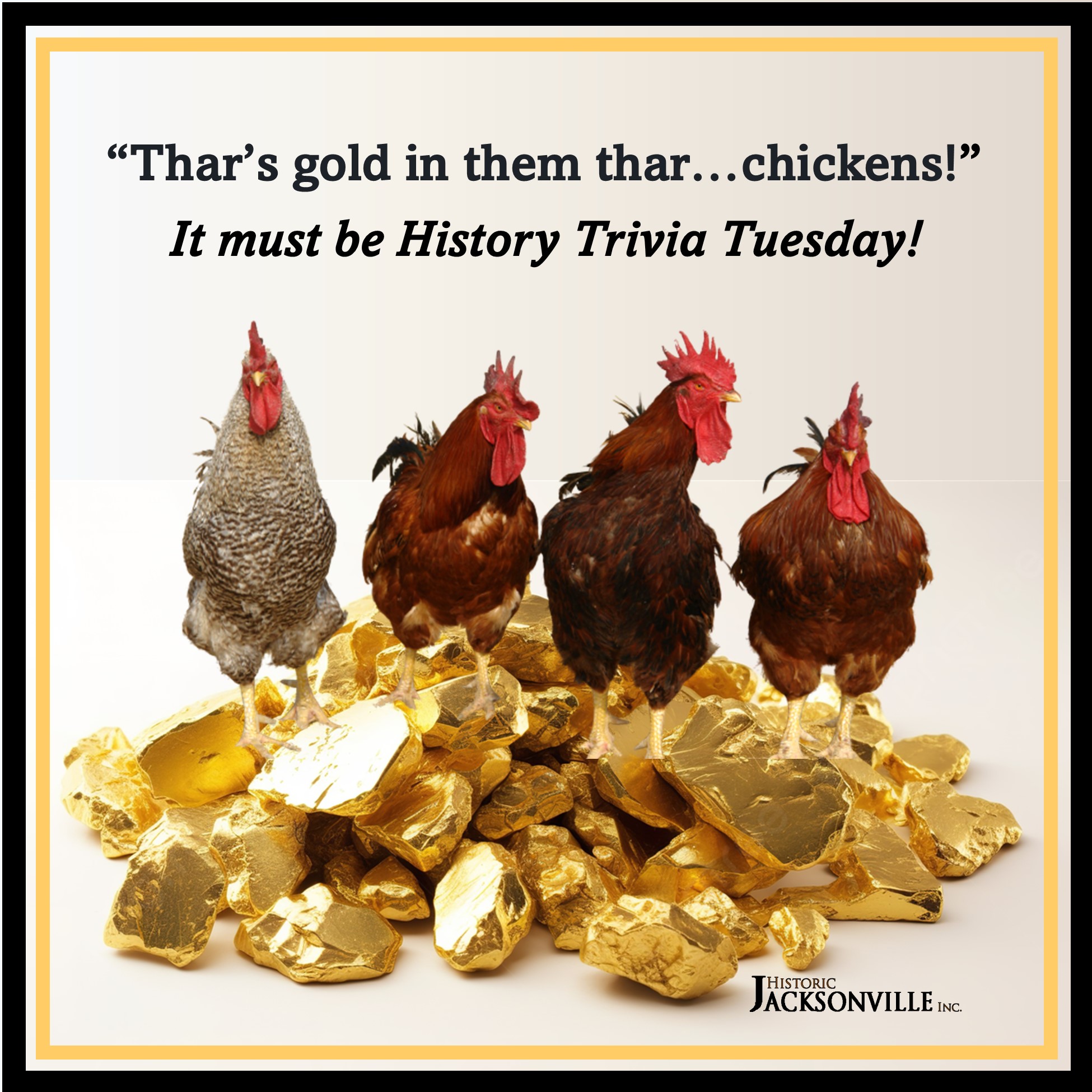

Golden Chickens

Historic Jacksonville, Inc. has often posted stories from Jacksonville’s original gold rush and from its second gold rush during the Great Depression of the 1930s. However, there may not have been that big a gap between the two!

We recently came across an article about a widow who had a cabin near Rich Gulch in the early 1900s. She had a fine garden, flanked with an extensive gravel bar, a memento of the days when the stream was lined with rockers, long toms, or sluice boxes.

In an “Oregon Journal” article by Fred Lockley, the widow said that she lived off her garden and her chickens. “After a heavy rain my chicken money brings in quite a bit extra.” Lockley asked what a heavy rain had to do with bringing in extra money from her chickens?

She went into the house and brought out a small bottle and, taking out the cork, said, “Hold out your hand and I will show you.” She poured a dozen or more small gold nuggets into Lockley’s hand and said, “My chickens range up and down the stream here and, after a heavy rain, they see these nuggets gleaming dully in the cracks of the bedrock, where the miners removed the gravel in the old days, and pick them up.

“I never sell my chickens alive. I sell the eggs, or I sell my chickens dressed, for I frequently get from their crops anywhere from a quarter’s to as high as several dollars’ worth of nuggets. The nuggets you have in your hand there are worth about $5. I got those from the crops of the last few chickens I killed.”

So now you know—“Thar’s gold in them that…chickens!” And who knows where else you may still find it!

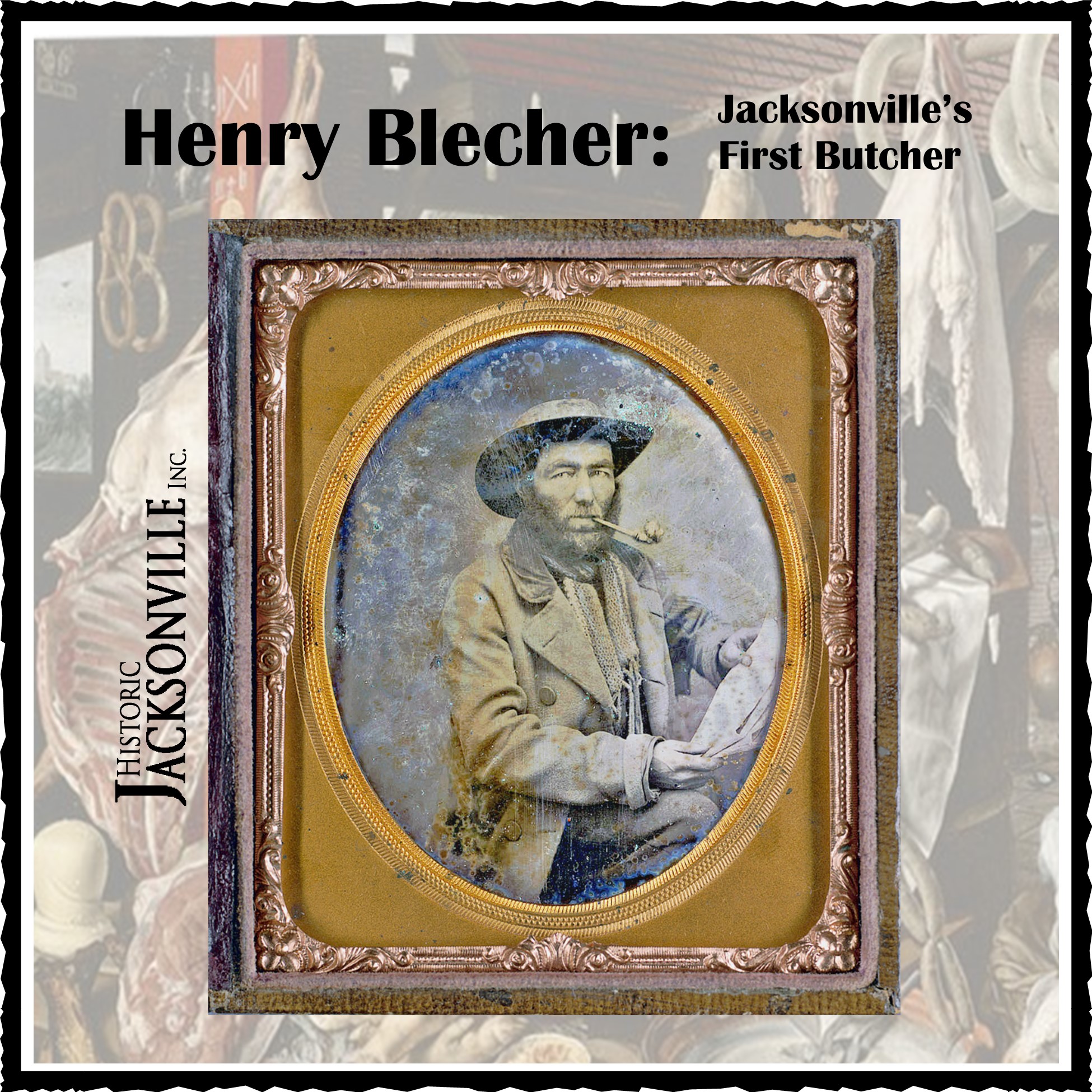

Henry Belcher

All of those 1852 gold miners had to eat, and, according to A.G. Walling, Jacksonville’s first butcher shop had opened within the year. Described as “one of the finest” (although we can’t imagine there was that much competition), it was owned by Henry Blecher, a native of Prussia. Born in 1822, he had immigrated to the U.S. in 1848. Undoubtedly, like many others, he followed the promise of riches to the West Coast. By the beginning of 1854, he was carrying “a heavy stock.” That undoubtedly included venison, chicken, pork, rabbit, beef, and probably sausage—common staples of the time.

The shop appears to have been located on South Oregon between California and Main streets, probably where the Orth building now stands. In fact, he may have joined or sold out to John Orth in the butcher business. We do know that he regularly provisioned the Jackson County jail, and in December 1875, he delivered 70,000 pounds of beef at $4.49 per hundred pounds to the Indian agent at Yainax, Oregon. He was regularly listed as one of Jackson County’s heaviest taxpayers.

We’re not sure who his suppliers were, but Blecher did own 1283 acres of land on Poorman’s Creek, 3 miles south of Jacksonville on the road to Sterling. We don’t know if he farmed or ranched the property, but 90 acres housed a dwelling, barn, and orchard. A fair amount of the acreage appears to have been forested since in 1891 he was hauling wood for the Rogue River Valley Railway between Jacksonville and Medford. Blecher passed away in 1900 at the age of 77. His property was inherited by his half brother and sister and by 1902 the Jacksonville Lumber Company had established a sawmill on the “old Blecher place.”

A few hard facts and a lot of “probablies and maybes.” Keep in mind there was no newspaper in Jacksonville until 1854 and earlier accounts rely on personal diaries, hearsay published in Portland or Yreka papers, and memoirs from much later years. Such are the basis of much of our early history….

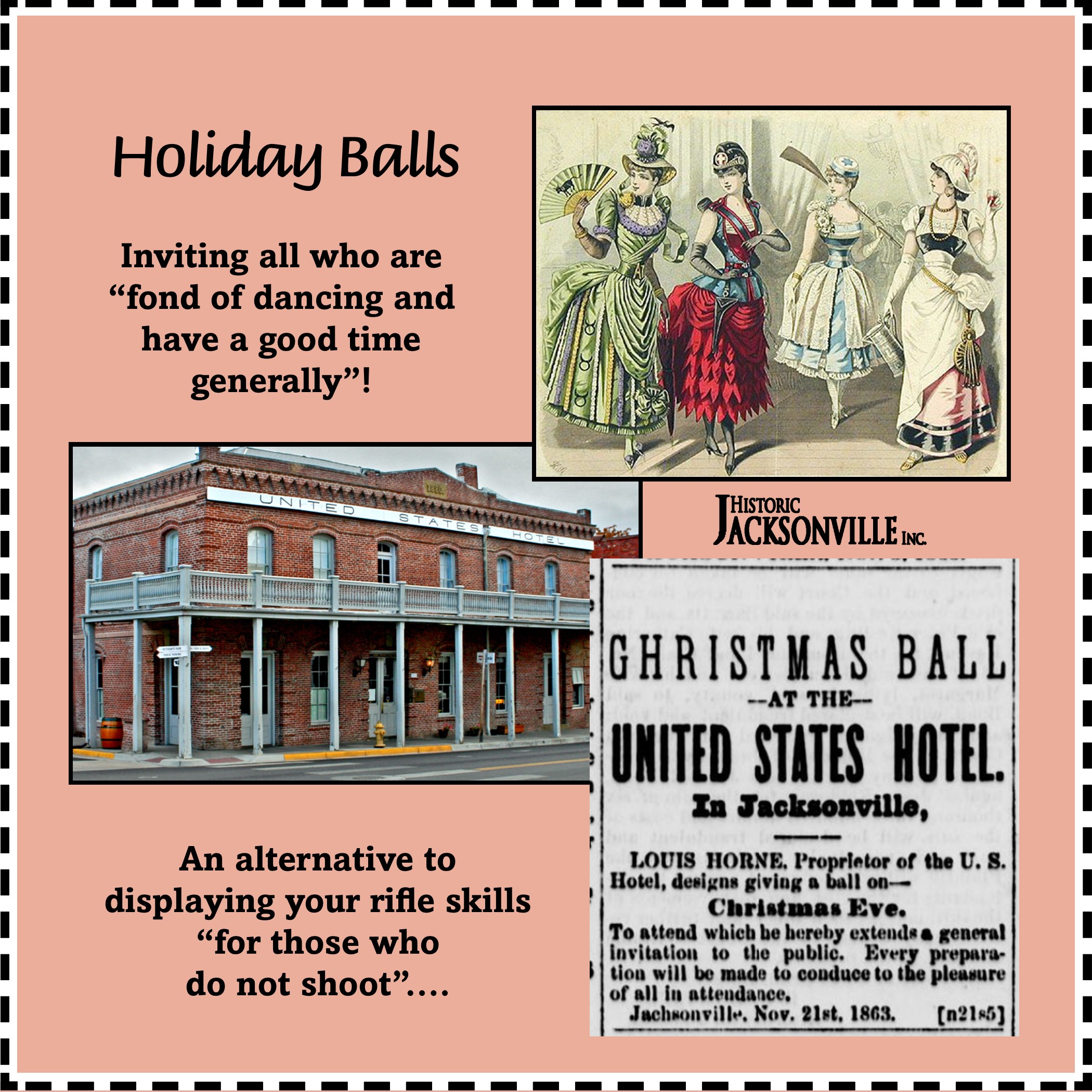

Holiday Balls

If you were back in 19th Century Jacksonville, you might be attending a dance or ball on New Year’s Eve! The U.S. Hotel (Horne’s Hall) was home to regular balls and Jacksonville’s Redmen’s Hall, the Masonic Hall, the Odd Fellows building, and Veit Schutz Hall all had ballrooms or dance floors, since weekly dances were a popular form of local entertainment. Masquerades, or fancy-dress balls, were particularly popular over the holidays. At masquerades, prizes were typically awarded for best costume. And it was also common for spectators to pay to watch the costumed partygoers entering the ball—like fans today paying to watch celebrities attend a gala or awards ceremony today. For Jacksonville’s 1901 New Year’s Eve ball, the local newspaper noted that a Portland costumer came down with trunk loads of costumes that could be rented or purchased for the occasion.

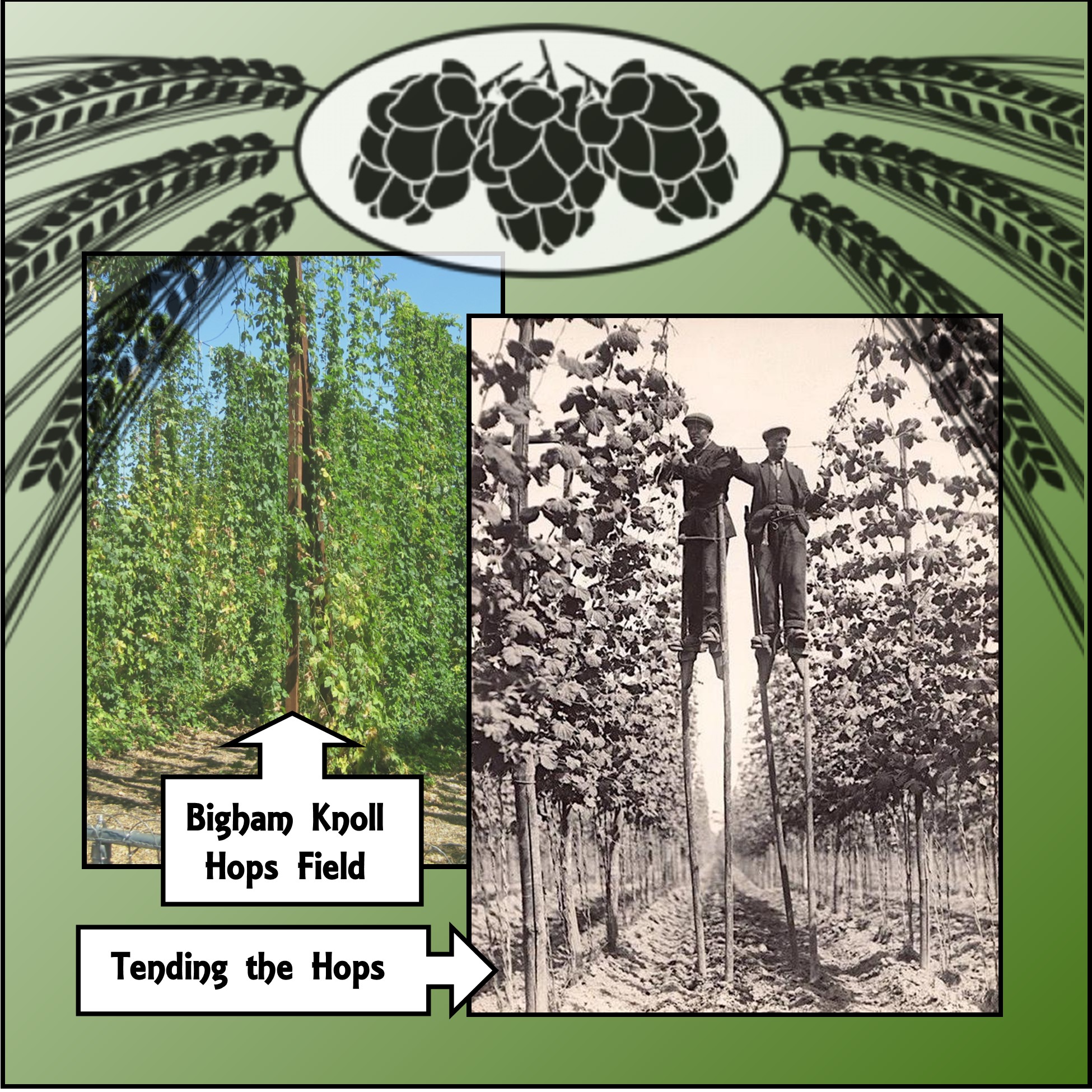

Hops Fields

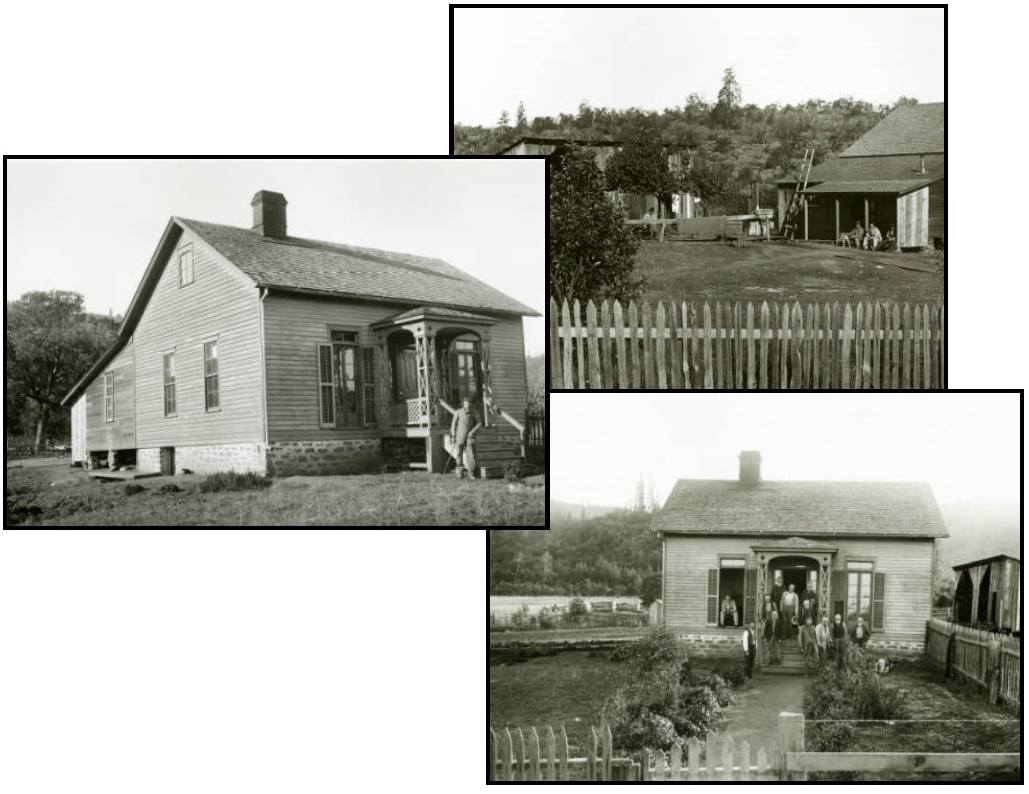

Jackson Country Poor Farm

Today we’re also asking for your help with a history mystery! We’re trying to locate Emil DeRoboam’s Jackson County Poor Farm. [See photos.] We recently told you how Emil DeRoboam was the farm’s superintendent. He apparently took over from his aunt, Madame Jeanne DeRoboam Holt, proprietress of the U.S. Hotel. She had obtained the contract for the county “poor hospital” in 1880, housing the indigent for $1.49 a day in a building she rented adjacent to her Franco-American Hotel, the current site of the Jacksonville Inn cottages. Emil apparently ran it for two years after her death in 1884. When he moved his family to Yreka, the inmates were relocated to J.M Lofland’s farm near Jacksonville. However, by 1888, Emil was back in town and purchased the 642-acre Bellinger land claim. In addition to farming the land, he obtained the contract for the county “poor farm” in his own right and ran it for almost 20 years until the county purchased a site near Talent. The Talent site, which operated until 1983, is now home to the Southern Oregon Educational Service District. But back to Emil. Where was his “poor farm”? It had to be somewhere near Bellinger Lane and his home at 3995 S. Stage Road. Can you help us locate it?

Jacksonville Leap Year – 1884

Since 2024 is a Leap Year, Historic Jacksonville, Inc. is wondering—does the “Ladies’ Law” still hold? According to tradition (which can be traced to 1288 and Margaret Queen of Scots), during a Leap Year a lady has the privilege of suggesting marriage between herself and a bachelor acquaintance. In the event of the gentleman’s refusal, he was expected to present the lady with some compensation, a more common one being a new black silk dress. We did find an 1885 newspaper quip with a niece asking her aunt why she had so many black silk dresses!

We don’t know how many Jacksonville ladies may have taken advantage of the role reversal tradition, but we do know that in February 1884, the “Oregon Sentinel” reported that local ladies held a “Leap Year’s party at Madame Holt’s Hall.” Prominent Jacksonville family names appear on the dance committee lists: Orth, Prim, Helms, Plymale, Linn, Hanley, Ulrich, Klippel, and Cameron among others. For the evening at least, the ladies adopted the following resolutions:

· Every lady is expected to act like a perfect gentleman.

· No gentleman will dance unless asked by a lady.

· No gentleman will walk across the floor unless leaning upon the arm of a lady.

· Any lady insulting a gentleman will be put out of the hall at once, and all gentlemen will be protected from rudeness while in the hall.

· Gentlemen will dance on the right side of a lady as a matter of course.

· Any ungentlemanly behavior on the part of a lady will be promptly checked by the floor committee.

· Any gentleman showing a lady attention shall be warned once and put out twice.

· Any gentleman asked by a lady to dance can excuse himself by fibbing about his engagement if he chooses, and all will be well.

We have not had a chance to check the local newspapers for any subsequent marriages, but we do suspect that a good time was had by all!

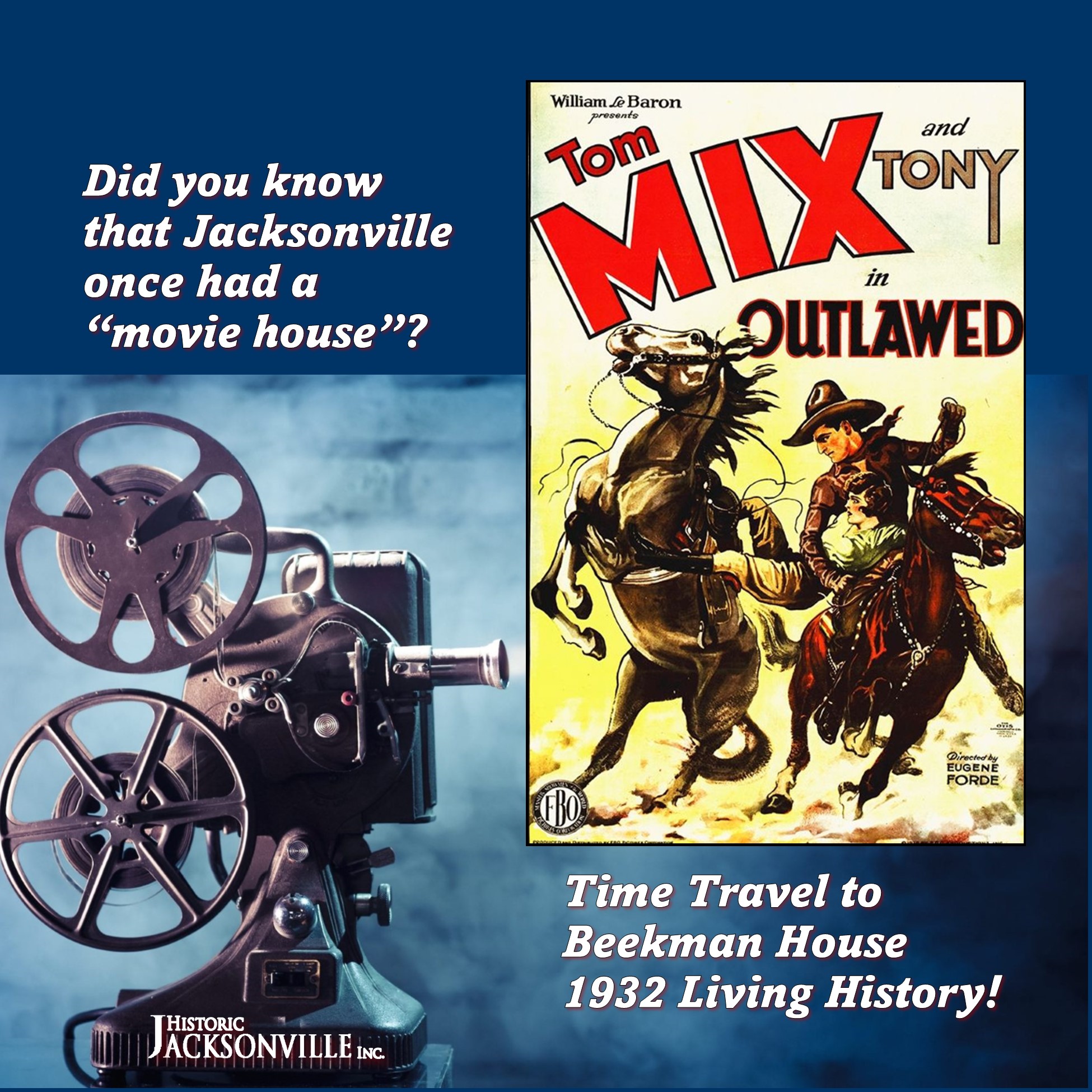

Jacksonville Movie House

Did you know that Jacksonville once boasted a movie theater? On November 21, 1929, “Outlawed,” starring cowboy Tom Mix and his horse Tony, opened Felton Franks’ new “movie house.” Located in the Kubli building at 115 W. California, it boasted a stage, a sloping floor, “attractive decorations,” and a seating capacity of 150. Franks promised shows 4 times a week, continuous performances from 7 to 11pm, and 3 complete weekly changes of program featuring “the very best of the big silent pictures” from Paramount, Universal, and FBO.

However, Franks’ timing was off, following so closely on the heels of the stock market crash of 1929 which ushered in the Great Depression. The movie house lasted into the early 1930s, but closed for lack of audience. Even though movies were a popular escape from the Depression, Jacksonville’s population had fallen to under 700 and many were “on the dole,” i.e., welfare.

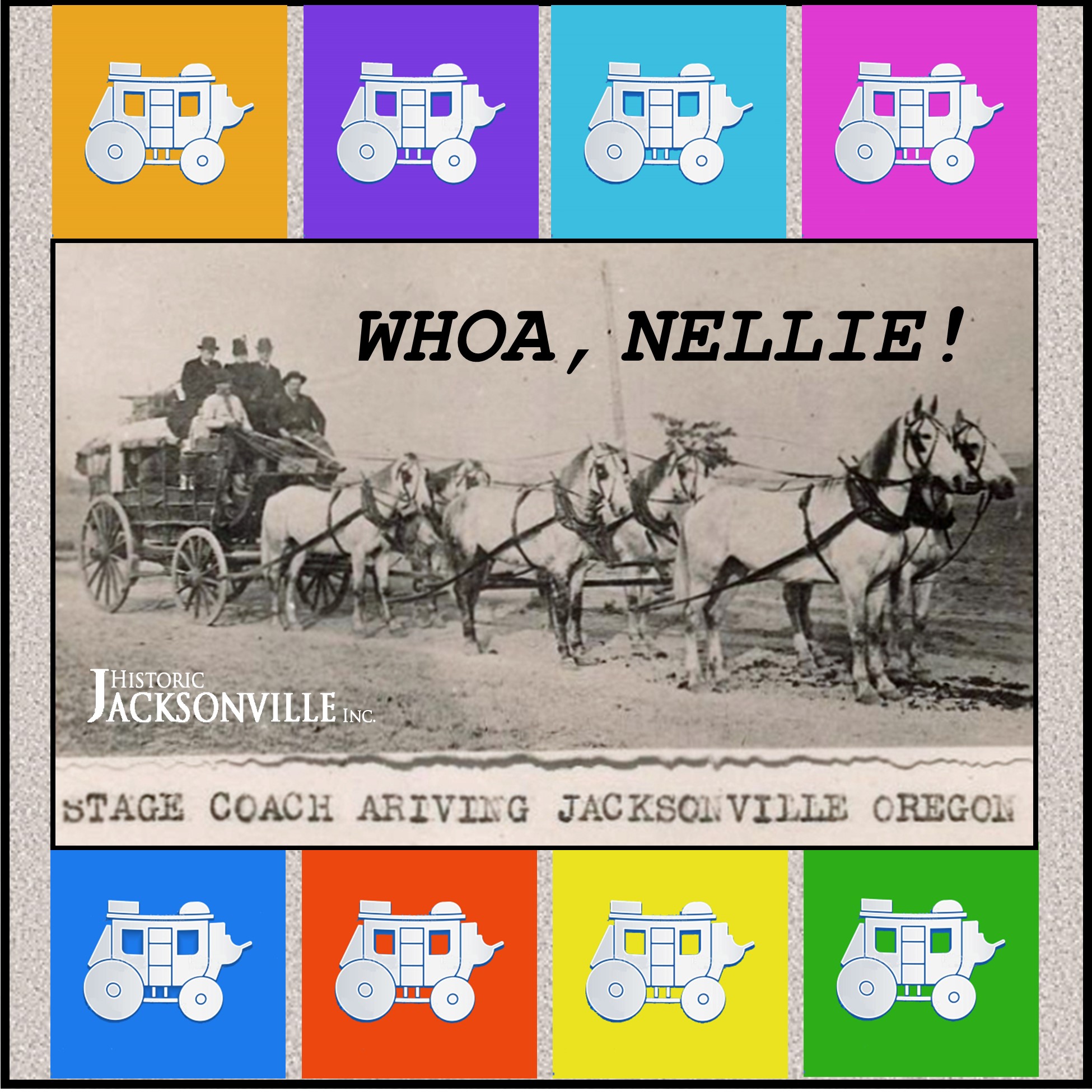

Jacksonville Stagecoach

Jacksonville’s Cannon

The mock cannon outside the Public Works shop behind Jacksonville’s City Hall serves as a tribute to the 6 pound brass field piece the Governor ordered for Jacksonville at the beginning of the Civil War. The original cannon, now housed in the Oregon Military Museum in Clackamas, was fired in honor of Union victories and on special post-war occasions. During a 1904 Grand Army of the Republic reunion, some local veterans staged their own celebration. Around midnight on Saturday, September 24, George “Bum” Neuber and some of his colleagues, under the supervision of town Marshal Bill Kenney, pulled the cannon to the middle of California Street, stuffed 6 woolen socks full of gunpowder down the barrel, and lit the fuse. The blast took out every window from 3rd to 5th streets, and left shattered doors, broken window frames, and cracked plaster in surrounding buildings. It took the local glazier 3 weeks to replace all the glass. Bum Neuber gladly footed the bill, declaring it “jolly good fun”!

The mock cannon outside the Public Works shop behind Jacksonville’s City Hall serves as a tribute to the 6 pound brass field piece the Governor ordered for Jacksonville at the beginning of the Civil War. The original cannon, now housed in the Oregon Military Museum in Clackamas, was fired in honor of Union victories and on special post-war occasions. During a 1904 Grand Army of the Republic reunion, some local veterans staged their own celebration. Around midnight on Saturday, September 24, George “Bum” Neuber and some of his colleagues, under the supervision of town Marshal Bill Kenney, pulled the cannon to the middle of California Street, stuffed 6 woolen socks full of gunpowder down the barrel, and lit the fuse. The blast took out every window from 3rd to 5th streets, and left shattered doors, broken window frames, and cracked plaster in surrounding buildings. It took the local glazier 3 weeks to replace all the glass. Bum Neuber gladly footed the bill, declaring it “jolly good fun”!

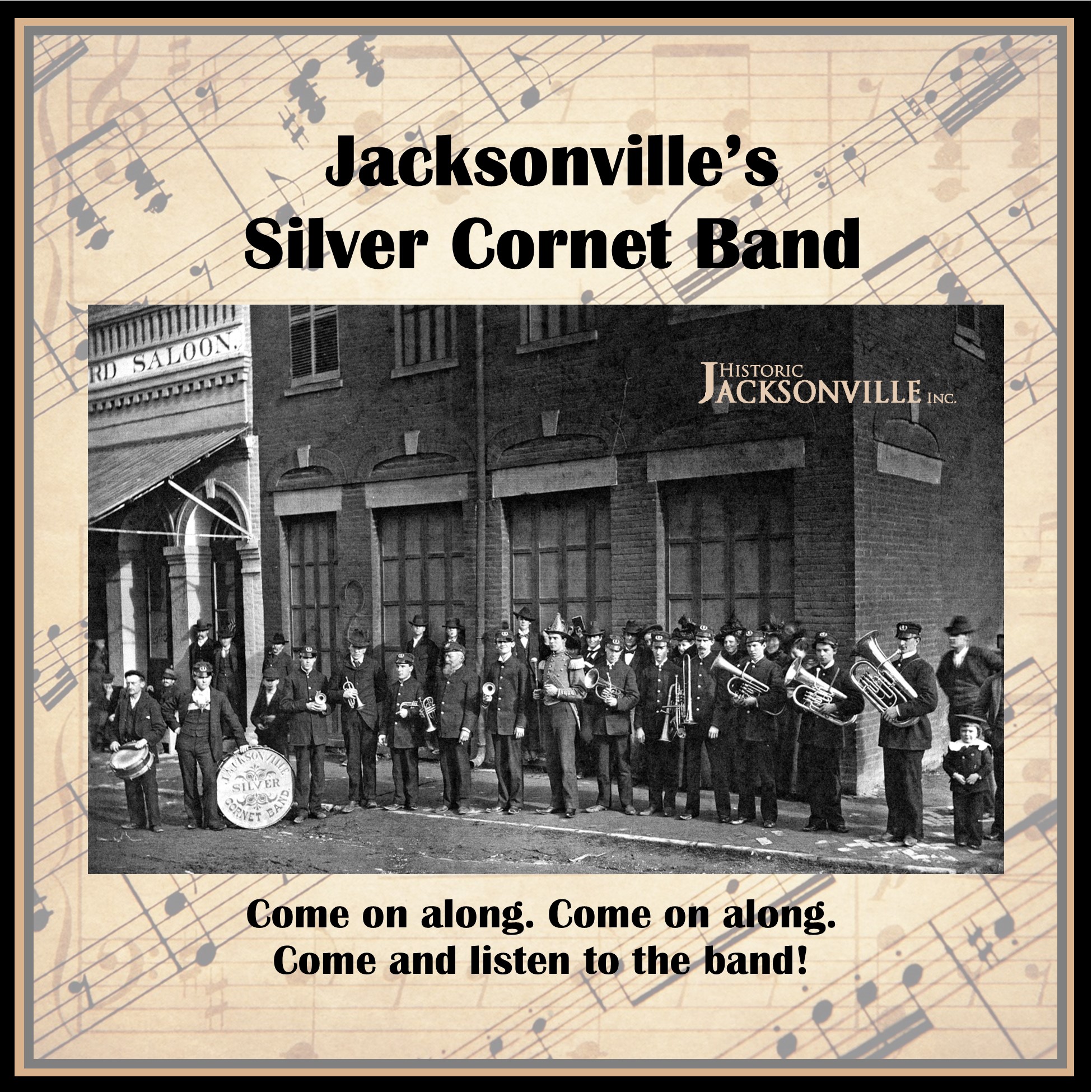

Jacksonville’s Silver Cornet Band

Music was part of Germanic culture and Jacksonville’s German speaking immigrants turned 19th Century Jacksonville into a musical culture center. Almost everyone in town owned a musical instrument, and many participated in Jacksonville’s Silver Cornet Band. The band was a popular attraction at town events and enlivened many social occasions. They even had their own band wagon which allowed them to “tour” the Valley. Members had to own their instruments, attend all rehearsals, and show up for performances.

Although the band won many contests, not all residents were fans. Someone described it as “adding a harmonious noise to the community and may have had something to do with driving the predatory wild animals out of the forest surrounding Jacksonville.”

James Mason Hutchings

Law and Order

Law and order in early Jacksonville might best be described as “catch as catch can.” In this case, it appears the murderer was not caught. The “Jacksonville Sentinel” reported a shooting that took place on January 18, 1857. About 2pm, A.J. Driskell, a local miner, was crossing South Oregon from the Brunner & Bros. store to the Table Rock Bakery, when he stopped midway to talk to a Mr. Denby. R.L. Williams stepped out of the shadows, told Denby to “get out of the way,” and fired a double-barreled shotgun loaded with buckshot at Driskell. Five of the balls passed through Driskell’s intestines. Driskell turned, ran a few paces and fell, but then got up, drew his revolver and started firing at Williams as Williams ran for cover behind the Maury & Davis store (site of Old City Hall). Williams prepared to fire again but, finding that Driskell had sought refuge back in the Brunner store, ran instead to the nearby livery stable where he had a horse already saddled. Williams was chased as far as the Applegate where his pursuers gave up. No further effort was made to capture him. Driskell died 5 days later, but not before Justice Hoffman took a formal affidavit in which Driskell implicated Williams and several other men “as being connected with a band of horse thieves” operating between California and the Dalles. What previous interaction Driskell and Williams had is unknown. Not exactly a “shoot out at the O.K. Corral,” but perhaps an indication of how effective law enforcement was when gold and gains were foremost in most people’s minds.

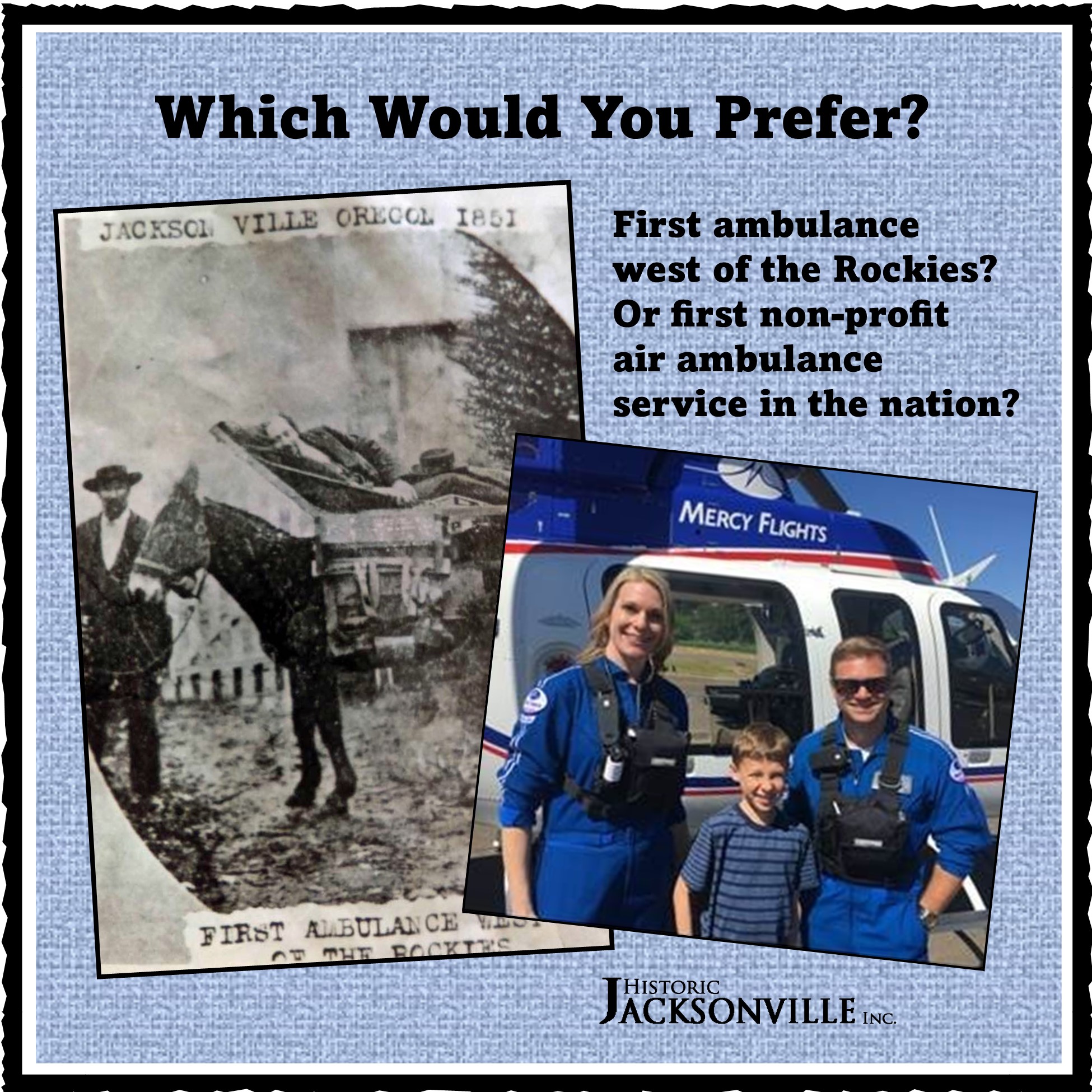

Mercy Flights

Did you know that Jacksonville reportedly provided the first ambulance service west of the Rockies? This newspaper photo pretty much speaks for itself. It also tells us to be very grateful for Mercy Flights, our local ground and air ambulance service! We should mention that Mercy Flights also boasts its own first—the nation’s first non-profit air ambulance service.

Mercy Flights was founded in 1949 by Medford air traffic controller George Milligan after a friend died of polio when he was unable to survive the drive to Portland. It added ground transportation in 1992, creating a regional medical transportation network. Normal ambulance service can be expensive–$1,200 or more for ground; $20,000+ for air. Mercy Flights offers membership subscriptions that accept any insurance you have as payment in full and discounts costs by 50% for those without insurance.

Because regional hospitals were so overwhelmed with COVID patients, Mercy Flights expanded its air ambulance service to Washington Nevada, southern California, and Idaho—wherever a physician can find an open bed and a doctor who will accept the patient.

So be grateful, very grateful, that you’re not reliant on a mule for medical transport!

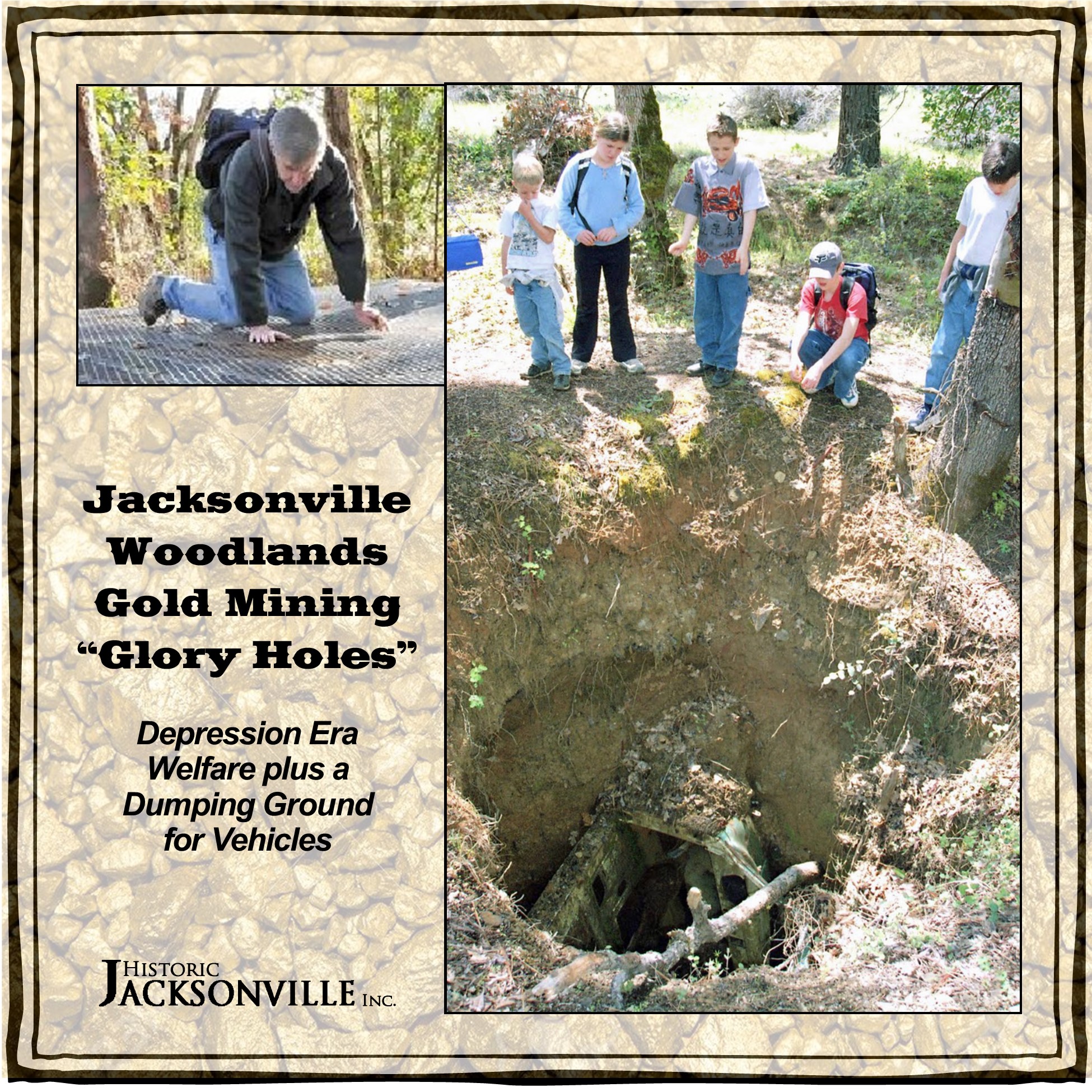

Mining Glory Holes

On several of Jacksonville’s Woodlands Trails, hikers see deep mining shafts called “Glory Holes,” remnants of 1930s Depression Era mining. They were named “Glory Holes” because they were get-rich-quick attempts at gold prospecting. For most, these typically 10- to 20-foot-deep holes held little glory.

One of these shafts at the junction of the Rich Gulch and Petard trails is particularly well known—at the bottom is a 1950s GMC pickup truck. A former owner of the Rich Gulch property reported 7 vehicles buried in various shafts. Most were dragged and dumped during the last half of the 1900s as a way of getting rid of them. It’s thought the truck was dropped into this 35-plus foot shaft to hold up the sides. Most of the holes have since been filled in. This particular shaft was designated as an “antiquity” under Rich Gulch’s National Historic Landmark status and has since been covered by a see-through metal lid for safety purposes.

Jacksonville’s original gold rush began in the spring of 1852, but during the 1930s Depression, Jackson County issued mining permits as an alternative to putting people on the “dole” (i.e., welfare). A miner could eke out enough residual gold to live on, perhaps $2 a day—double local wages. A few found actual riches. As a result, most of the town itself was undermined, with the exception of a portion of North 5th Street that included New City Hall (the historic Jackson County Courthouse) and St. Andrews Methodist-Episcopal Church. The City of Jacksonville refused to permit it.

Mining Sink Holes

Given the response to last week’s Depression Era gold mining “glory holes” in the Jacksonville Woodlands, Historic Jacksonville, Inc. thought we’d follow up with a little more information on Jacksonville’s second gold rush. As an alternative to putting residents on the “dole” during the 1930s, the County gave out mining permits, allowing residents to dig for any residual gold lingering from the 1850s. Some got lucky, but most latter-day miners only found enough gold to live from day to day. Still $2 a day was more than most jobs paid—assuming you could find one.

Most mining shafts were dug in backyards, but some residents had sufficient moxie to burrow under the town’s commercial buildings. According to 1935 newspaper accounts, 4th Street had several dips in it; on Main Street, “the bottom fell away from light poles, leaving them suspended by the wires on the cross arms.” The shaft pictured here is in what is now the parking lot behind Jacksonville’s post office and Visitors Center, the old Rogue River Valley Railroad station.

Almost every inch of Jacksonville was “undermined.” The result is periodic “sink holes” opening over old mine shafts around town. In just the past few years we’ve had sink holes opening behind the Jacksonville Inn, in the post office/Visitors Center parking lot, and in Ray’s Market’s parking lot—all remnants of what individuals might do for what one journalist described as a “ham-and-eggs” existence.

Old Stage Road

Have you ever wondered about the names “Old Stage Road” or “South Stage Road” for the streets leading north and south from Jacksonville? Well, you can’t have stage service without roads. Regular stage service for the area did not begin until the mid-1850s and the stops were Ashland, Jacksonville, and Rock Point (near Gold Hill).

The route to Yreka was not a road; it was a rough and difficult passage best made on foot or horseback. The Siskiyou Mountain Wagon Road, a toll road and the first “engineered” road over the mountain crest that separates California and Oregon, did not open until August 1859.

Stages could now run from Sacramento, California, to Portland, Oregon. The stage and freight companies carried passengers at a charge of 12½¢ per mile. Freight was hauled for 4¢ per pound, in large, heavily built wagons. What made the service profitable was a lucrative contract to carry the U.S. Mail. This 710-mile route was the second longest stage run in the U.S.

So why the strange 90 degree turns in the road? If a land claim holder refused permission to pass through his property, the road had to go around it.

Although pack trains occasionally carried passengers, the stage and freight wagons were the principal methods of transportation and passenger travel until 1884, when the railroad entered the Rogue River Valley. With completion of the railroad over the Siskiyous, the last stagecoach traversed the pass on December 18, 1887, the day following the official Golden Spike ceremony in Ashland.

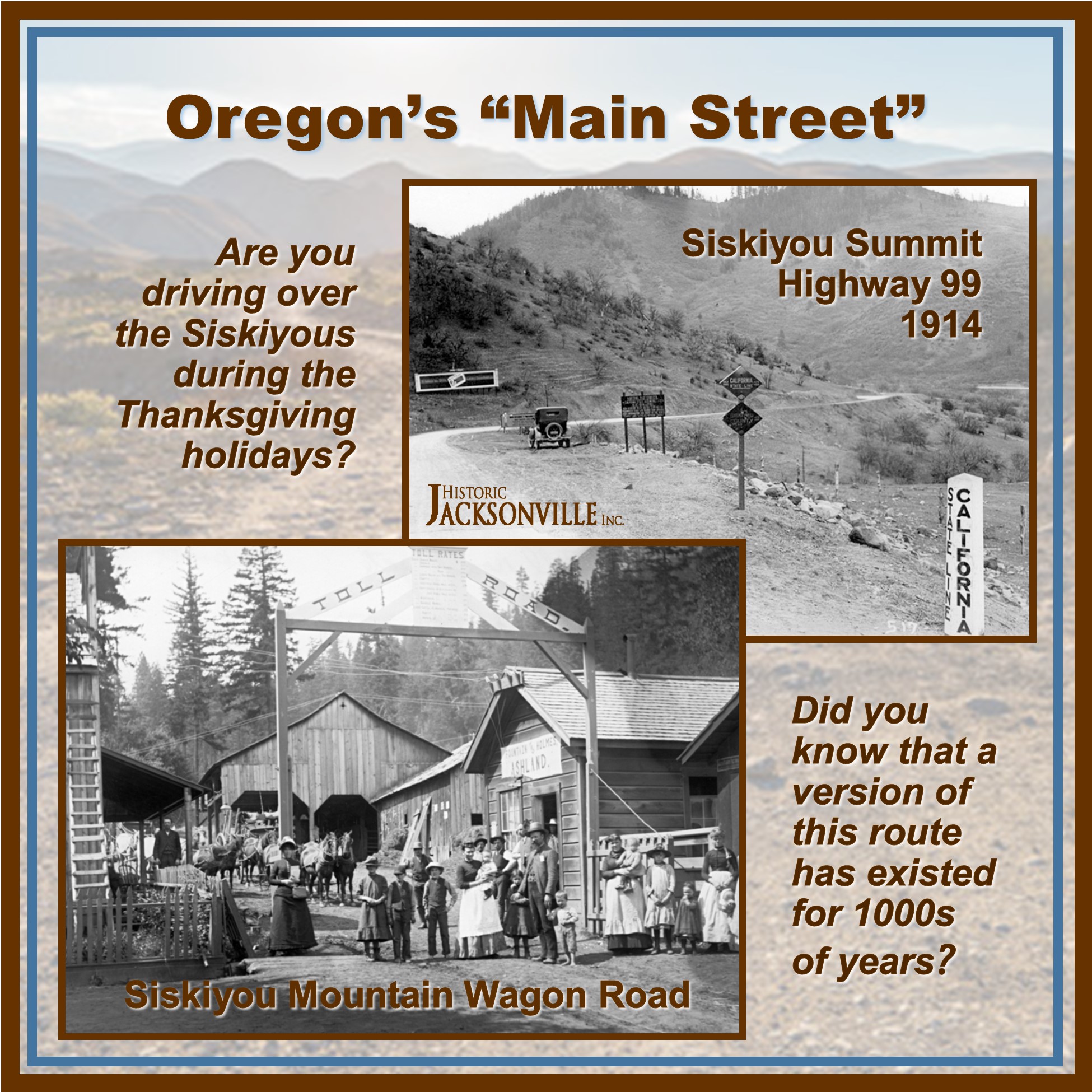

Oregon’s Main Street

The Tuesday before Thanksgiving has historically been the most heavily traveled day of the year. Will you be driving over the Siskiyous to visit family or friends in California? Or looking forward to guests making the trip in reverse? If so, you or they will be traveling “Oregon’s Main Street.” Did you know that some version of that route has been followed for thousands of years?

When Cornelius Beekman rode his 67-mile express route between Jacksonville and Yreka in the 1850s, he followed the Siskiyou Trail blazed by Hudson Bay Company trappers in the 1820s that roughly followed an ancient network of Native American footpaths. In 1837, an enterprising Californian spent 3 months driving 700 cattle over the trail to sell to British and American settlers in Oregon, widening and establishing the trail in the process.

The 1848 discovery of gold sent Oregonians pouring over the pass in search of riches; the 1851 discovery of gold in Southern Oregon reversed the migration. By the 1850s the “population explosion” demanded a real road. In 1859, a toll road, the Siskiyou Mountain Wagon Road, the first “engineered” road over the Siskiyous opened. A little excavation was done, a few culverts put in, but the route varied only slightly from that of the Trail.

The toll road continued to operate until 1915, when the Pacific Highway, a “national auto trail,” was constructed over essentially the same route. It was straighter and wider, but it was still a dirt road. A “Get Out of the Mud” campaign in the 1920s turned it into a paved surface. In 1945, the Oregon Highway Commission designated the Pacific Highway the “official inter-regional north-south route through Oregon.” The federal government designated it U.S. Highway 99.

When the old highway was replaced by I-5 in 1967, bits and pieces of the Siskiyou Road were incorporated into the Interstate. So the next time you cross the Siskiyous, appreciate your ease of travel and give a salute to “Oregon’s Main Street”!

Peter Britt’s Gold Ingot

This small gold ingot weighing 2.2 grams was made from gold dug in Jacksonville by Chinese miners who camped on property owned by photographer Peter Britt. At a time when most Westerners treated minorities poorly, Britt was noted for his friendly dealings with the Chinese. The miners refined, cast and presented the ingot to Britt around 1854. The characters on the front translate as “Heaven Original” and “Sufficient Gold”; the back is blank. At the time coins were in limited supply and most business was done by barter or by payment in gold. This ingot would have been intended for use as money. According to Britt’s son Emil, it was given to his father as a token of appreciation.

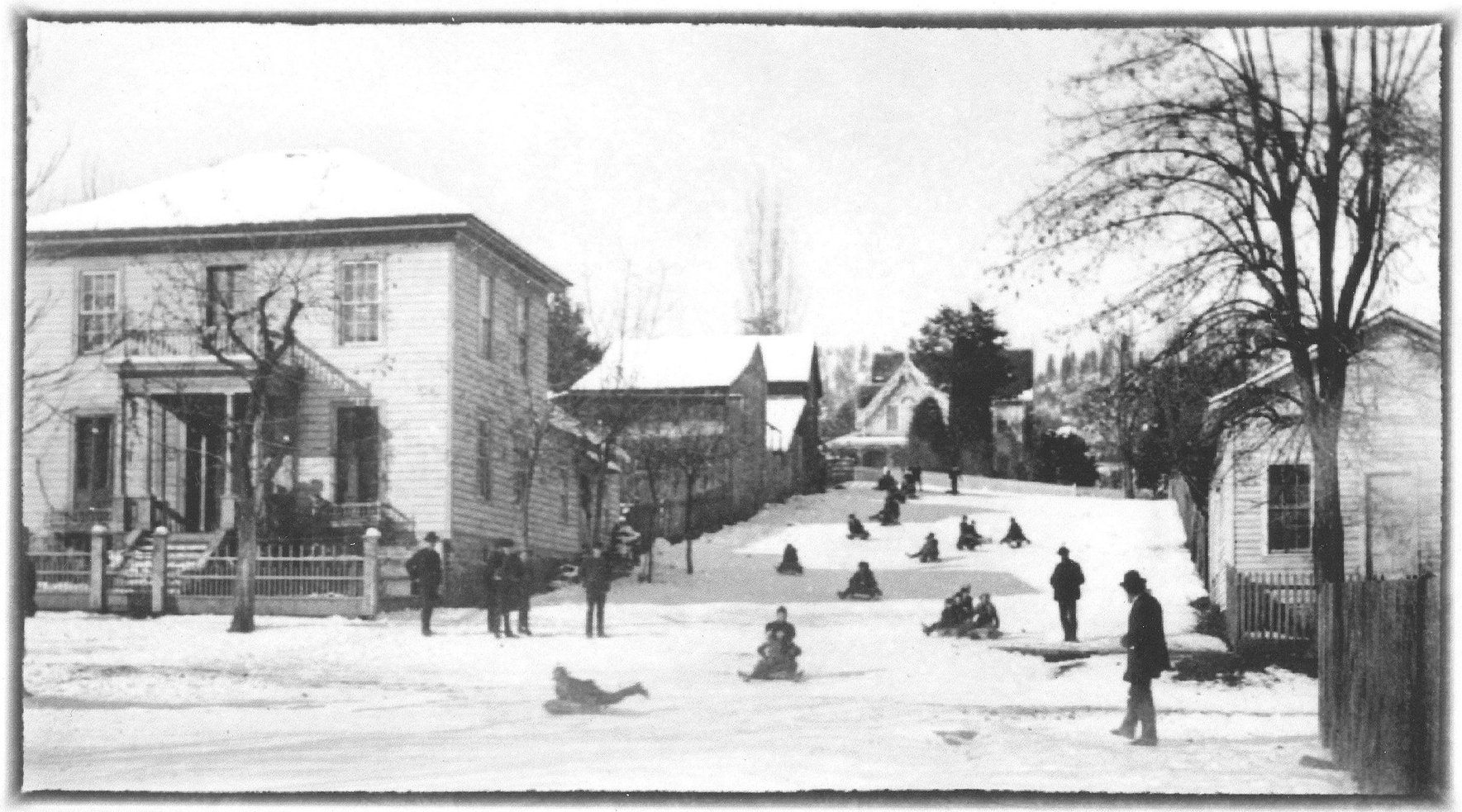

Pine Street Snow Sledding

We’ll wish you a Merry Christmas and some very happy holidays with this photo from the late 1800s of sledding on Jacksonville’s Britt Hill. The vantage point is the corner of Pine and South Oregon streets. Herman von Helms house is on the left corner with stables and a shed behind it, and Peter Britt’s house can be seen at the top of the hill on 1st Street.

Reader’s Digest

Did you know that the “Reader’s Digest” magazine was inspired by a Jacksonville event? DeWitt Wallace, the founder of the Reader’s Digest, conceived a revolutionary method for condensing magazine articles while witnessing a 1911 trial in the Jackson County courtroom—the 2nd floor of what is now Jacksonville’s New City Hall when the building was still the county courthouse.

The year was 1911. DeWitt was 22 and working on completing his education at Berkeley. He was spending several weeks in Southern Oregon peddling Oregon maps door-to-door as he worked his way through college. On his first day, he sold 12 maps around Medford, although he had to walk 25 miles to do so.

Not discouraged, he stayed on the move, talking with veteran salesmen in hotel lobbies and picking up their stratagems. As he widened his circle of acquaintances, DeWitte discovered that he could learn something from anyone he could talk to. The average person might not have an academic degree, but his intelligence was not to be underestimated. Most were as curious and hungry for knowledge as he was.

After walking out to Jacksonville one day, DeWitt took a break from the weather, waiting out a rainstorm in the Jackson County courtroom. While drying out, he witnessed a battle of wits between two lawyers. He noticed how the two opposing lawyers were able to condense the facts of the case into tight and easily understood arguments. DeWitt realized that he could apply that same technique of examining witnesses to every imaginable life situation. And thus was born a method for taking articles of lasting interest and condensing them into a shorter and more readable form.

The trial proved to the young student that marvelous sources of insight were everywhere—overlooked, undetected, but to be had for the asking. So, Jacksonville’s New City Hall, Jackson County’s 1884 courthouse, helped change the history of America’s reading habits!

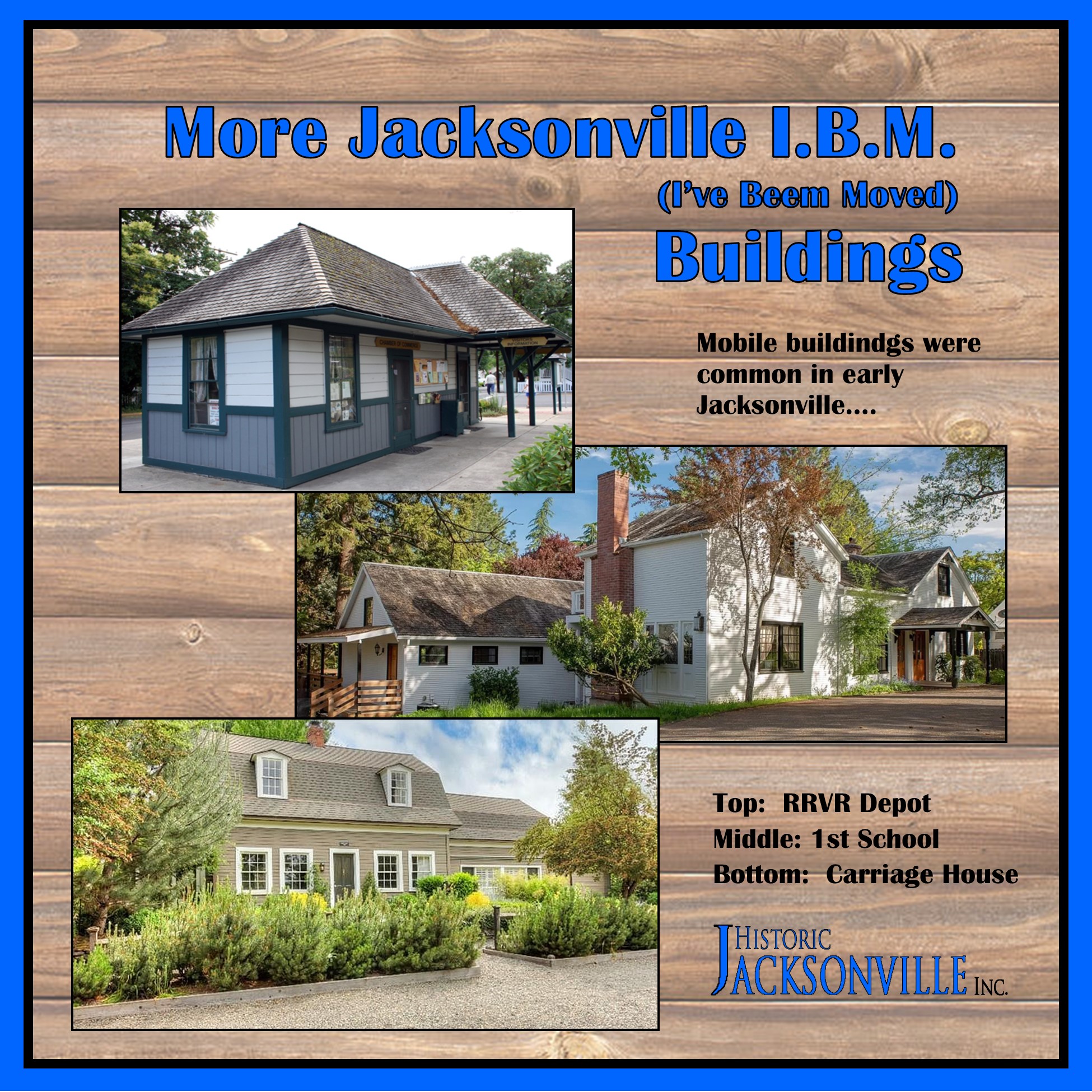

Relocated Buildings #1

Employees of I.B.M. used to joke that the initials stood for “I’ve Been Moved” since they were relocated so frequently. Well, in early Jacksonville, it was buildings that were frequently relocated. Here are three with that distinction.

When St. Andrews Methodist Episcopal Church was built in 1854, the church faced 4th Street. Three years after the new Jackson County Courthouse was completed in 1884 and 5th Street became the main route to Medford, the building was rotated and moved to face the new thoroughfare.

The “Gwinn House” located at 415 East C Street was purchased from the original builder in September 1859 “for the County Clerk’s office, Sheriff’s office, and jury rooms…and removed to the Court House block” where it stood at the corner of 6th and C streets. It served those functions for the next 25 years until the County Clerk and Sheriff moved into the new brick courthouse in 1884. Sometime after 1907, the house was moved to its present site.

The Applebaker Barn, located at the corner of North 3rd and D streets, was originally a steam grist mill, built in 1880, and located about 1 mile south on 3rd. At one time it ranked third in the state in flour production. In 1915, Joseph Applebaker dismantled, moved, and reconstructed the building at its present location to serve as his blacksmith’s shop.

Relocated Buildings #2

The southern portion of the house at 560 North Oregon Street is believed to have been Jacksonville’s first schoolhouse, but this was not its original site. Constructed in 1856, records show it was located on the opposite side of North Oregon and about ¼ mile farther north. The house was deeded to Robert Dunlap in payment of $137 he was owed “for improvements – digging well, making fences, walks, etc. – about the new school house” that had been constructed on Bigham Knoll in 1868. Dunlap, best known as the cemetery sexton, moved the old schoolhouse to this lot where it became his home.

Most know that the Jacksonville’s 1891 Visitors Center building was originally the depot for the Rogue River Valley Railway. The small spur rail line was the town’s attempt to maintain regional prominence after the Oregon and California Railroad bypassed Jacksonville in the 1880s in favor of the flat valley floor. But it was too little too late. The railway ceased operation in 1924 and the depot was abandoned. In the 1960s, the depot became the headquarters of the Jacksonville Boosters Club. Although the building remained on the same site, it was rotated 90 degrees so that it faced the new post office building rather than Oregon Street.

The central portion of the lovely home at 465 East C Street known as the “Carriage House,” was originally a barn constructed in the 1880s, probably by Max Muller. The next owner of the property built the right portion of the house as a carriage house around 1908. When George and Doris Brewer purchased the property in the 1960s, they jacked up the old barn, put it on skids, and pulled it to a cement foundation. They then moved the carriage house from its original location, turned it 180 degrees, and attached it to the barn. The current structure was finished with materials salvaged from historic properties throughout the Valley.

Rudolph Red-Nosed Reindeer

Bob May was not feeling much comfort or joy as the 1938 holiday season approached. A 34-year-old ad writer for Montgomery Ward in Chicago, May was exhausted and nearly broke. His wife, Evelyn, was bedridden, on the losing end of a two-year battle with cancer. This left Bob to look after their four-year old-daughter, Barbara.

One night, Barbara asked her father, “Why isn’t my mommy like everybody else’s mommy?” As he struggled to answer his daughter’s question, Bob remembered the pain of his own childhood. A small, sickly boy, he was constantly picked on and called names. But he wanted to give his daughter hope and show her that being different was nothing to be ashamed of. More than that, he wanted her to know that he loved her and would always take care of her. So he began to spin a tale about a reindeer with a bright red nose who found a special place on Santa’s team. Barbara loved the story so much that she made her father tell it every night before bedtime. As he did, it grew more elaborate. Because he couldn’t afford to buy his daughter a gift for Christmas, Bob decided to turn the story into a homemade picture book.

In early December, Bob’s wife died. Though he was heartbroken, he kept working on the book for his daughter. A few days before Christmas, he reluctantly attended a company party at Montgomery Ward. His co-workers encouraged him to share the story he’d written. After he read it, there was a standing ovation. Everyone wanted copies of their own. Montgomery Ward bought the rights to the book from their debt-ridden employee. Over the next six years, at Christmas, they gave away six million copies of Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer to shoppers. Every major publishing house in the country was making offers to obtain the book. In an incredible display of good will, the head of the department store returned all rights to Bob May. Four years later, Rudolph had made him into a millionaire.

Now remarried with a growing family, May felt blessed by his good fortune. But there was more to come. His brother-in-law, a successful songwriter named Johnny Marks, set the uplifting story to music. The song was pitched to artists from Bing Crosby on down. They all passed. Finally, Marks approached Gene Autry. The cowboy star had scored a holiday hit with “Here Comes Santa Claus” a few years before. Like the others, Autry wasn’t impressed with the song about the misfit reindeer. Marks begged him to give it a second listen. Autry played it for his wife, Ina. She was so touched by the line “They wouldn’t let poor Rudolph play in any reindeer games” that she insisted her husband record the tune.

Within a few years, it had become the second best-selling Christmas song ever, right behind “White Christmas.” Since then, Rudolph has come to life in TV specials, cartoons, movies, toys, games, coloring books, greeting cards and even a Ringling Bros. circus act. The little red-nosed reindeer dreamed up by Bob May and immortalized in song by Johnny Marks has come to symbolize Christmas as much as Santa Claus, evergreen trees and presents. As the last line of the song says, “He’ll go down in history.”

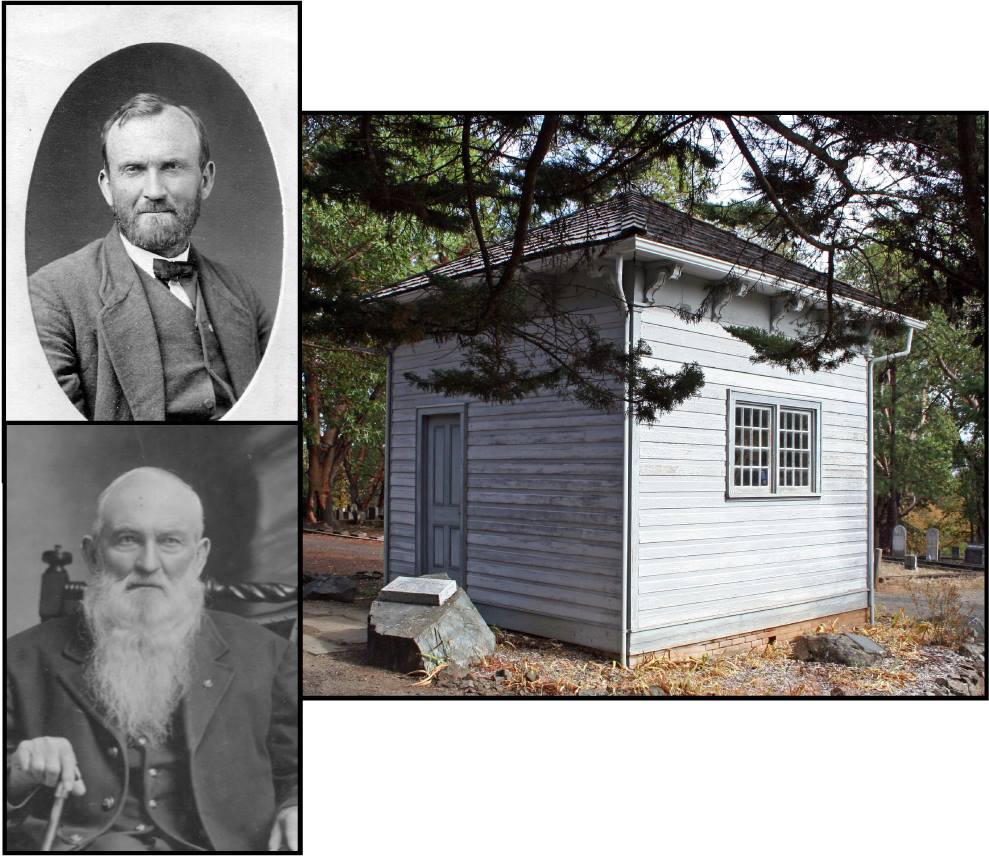

Sexton’s Tool House

In 1863 R. Sergeant Dunlap was appointed the first sexton of Jacksonville’s Pioneer Cemetery. He served in that capacity for many years – maintaining the cemetery grounds, selling plots, digging graves, and keeping the cemetery records. However, what’s known as the Sexton’s Tool House at the top of Cemetery Road was not constructed until 1878. The tool house also doubled as a mortuary. An underground vault provided storage for bodies when the ground was too frozen or too soggy to dig.

Skunked

Courtesy of the January 7, 1938, “Medford News”, it seems that Mrs. Cleora Bixby, who lived on the Jacksonville-Phoenix road, never had much use for skunks. When they started getting into her chicken coop, she took it upon herself to do something about it.

Someone told her that if she’d grab a skunk by the tail and hold it up, the skunk couldn’t spray. So the next time she heard a skunk in her pen, she snuck up on it and grabbed its tail. But now what to do with it?

She set out to a neighbor’s house, holding the skunk at arm’s length by the tail. It was no short walk, and the skunk started to get heavy. When the neighbor refused to have anything to do with the skunk, there was nothing to do but turn around and walk home. By the time she got there, her arm was almost paralyzed, and Mrs. Bixby was desperate. She decided to try cracking the skunk’s head against a post, but as she swung it around, she slipped, lost her grip, and the skunk landed on top of her. The result was very unpleasant to say the least.

Some days later, she heard another skunk in her chicken coop. She had no intention of grabbing it by the tail, so decided to dispatch it right away. She hurried out of the house, leaving the light on and the kitchen door open.

Mrs. Bixby’s efforts were partially successful. The skunk fled the chicken coop, but in a dash for safety, spied the open kitchen door and fled inside and under the bed. Well, you can guess the rest! The skunk exited the bedroom…and this life. Mrs. Bixby opened all the windows to the January air and abandoned the bedroom herself, at least for some days….

Snafu #1

Snafu #2

Snafu #3

Snafu #4

Stage Travel Have you ever wondered what it would be like to ride in a stagecoach? An 1865 traveler between Jacksonville and Yreka wrote about the “luxury” of travel in a stagecoach, or “mud wagon,” as they were called.

Have you ever wondered what it would be like to ride in a stagecoach? An 1865 traveler between Jacksonville and Yreka wrote about the “luxury” of travel in a stagecoach, or “mud wagon,” as they were called.

Picture a covered wagon. “Inside there are three seats, cushioned with leather cushions, more solid in feeling than the boards beneath, while the floor has several good large cracks, suitable for the free circulation of cold air, and which are highly instrumental in making the feet very uncomfortable. The backs of the seats are strips of cushioned boards, which reach just to that place in one’s back where a little support is ever so agreeable, and yet fails to reach it so universally that the spinal column weakens after a few miles’ riding, and the inclination is to get into a variety of positions, more to be felt than enjoyed. The curtains, devoted to the ‘comfort of passengers,’ have several air holes, or rather ventilation places, through which the wind makes a very sad and deplorable squeak as it squeezes through and pinches the auricular attachments of one’s aching head.

“A ‘stage’ has capacities for carrying freight, mail and passengers, of enormous amplitude. After piling on the small effects of passengers—twelve or fourteen large trunks, six or seven valises and as many blankets, baskets and bundles—the mail is added, sometimes ten or more bags; then express boxes, made of pine wood, but mounted with an iron lock large enough to use on a London penitentiary; then a few boxes ‘going by express.’

“A variety of loading is added, a Mexican saddle and a box of apples; then a ham…then a box of candles, a few pounds of old cheese, a pair of boots, …a small chicken coop and a new shovel for Smith, on the summit; a keg of mackerel, a bottle of old rye, a bag of corn and case of kerosene oil….”

And did we mention that if the wagon gets stuck in the mud, the passengers have to get out and push!

Stagecoach Rides

Before the Jacksonville Trolley began offering narrated history tours, visitors and residents alike could board a stagecoach operated by George McUne for a 15-minute tour of the town. After traveling in a covered wagon from Independence, Missouri, to Oregon as part of Oregon’s 1959 Centennial Wagon Train, McUne had sent to the Smithsonian for original Wells Fargo stagecoach plans and handcrafted a replica. In 1961, he began offering stagecoach tours of Jacksonville. The coach carried 12 to 15 passengers and was drawn by his reliable mules, Fibber and Molly. McUne would share stories about the discovery of gold, President Hayes’ visit to Jacksonville, the West’s last great train robbery, and other local tales. And tours always included a robbery at the Beekman Bank. McUne’s stagecoach rides were the genesis of what became Jacksonville’s original Pioneer Village with its array of “rescued” historic buildings and its multiple attractions.

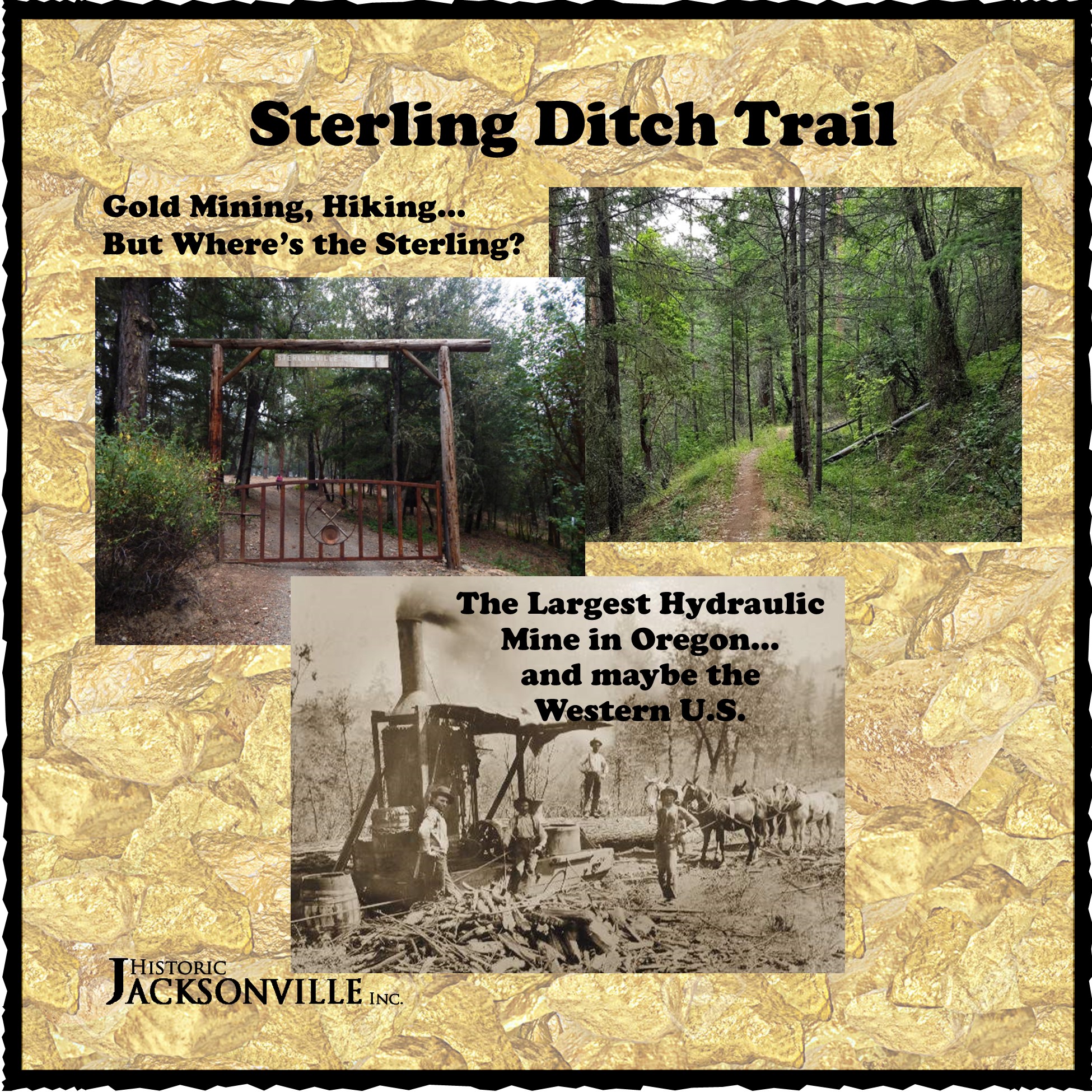

Sterling Ditch Trail

With warm weather and sunshine, most of us are just itching to enjoy outdoor activities, so how about a hike on the Sterling Ditch Trail. Just 8 miles south of Jacksonville, the trail offers year-round intermediate level hiking, mountain biking, and equestrian opportunities. But silver was never mined here, so where does the name come from?

Sterlingville was founded in 1854 when two miners named James Sterling and Aaron Davis discovered gold in nearby Sterling Creek (named after Sterling of course). Word leaked out that gold had been found, and within two years Sterlingville was home to over 800 people. Soon there were general stores, a warehouse, boarding houses, a bakery, a casino, a dance hall, saloons, a blacksmith shop, a barber shop, and many houses. At its peak Sterlingville had a population of over 1,500. It even had a school district and a post office.

In 1877, the newly founded Sterling Mine Company built the Sterling Ditch, diverting water 23 miles from Little Applegate River for hydraulic mining of gold and chromite. Sterling Mine quickly became the largest hydraulic mine in Oregon, and possibly the entire western United States.

But as the gold ran out, the population of the town declined. During the Great Depression, Sterlingville saw a revival of hydraulic mining, but after the mines closed in 1957, the town was abandoned, and nature eventually reclaimed the buildings. Today, the cemetery—and the Sterling Ditch Trail—are the only remaining signs of Sterlingville’s existence.

Sterlingville Cemetery

Both John Cantrall and Patrick Fehely, featured in our last 2 History Trivia Tuesdays, mined in Sterlingville, located about 6 miles south of Jacksonville. An entire town sprang up after miners James Sterling and Aaron Davis struck gold in 1854 in nearby Sterling Creek. With the gold miners came boarding houses, saloons, general stores, a casino, a dance hall, a barbershop and blacksmith shop and many houses. Within 2 years Sterlingville was home to over 800 people; at its peak Sterlingville had a population over 1,500. Jacksonville’s South 3rd Street (shown here in front of the Fehely House) connected to the Sterlingville Road. In 1877, the Sterling Mine Company built the Sterling Ditch, diverting water 23 miles from the Little Applegate River for hydraulic mining. Sterling Mine quickly became the largest hydraulic mine in Oregon. But as the gold diminished, so did the township. After the Great Depression, what little business and population were left slowly faded away and nature eventually reclaimed the buildings. Today, the cemetery is the only remaining sign of Sterlingville’s existence. Patrick Fehely and his wife, Sarah Jane, are both buried there.

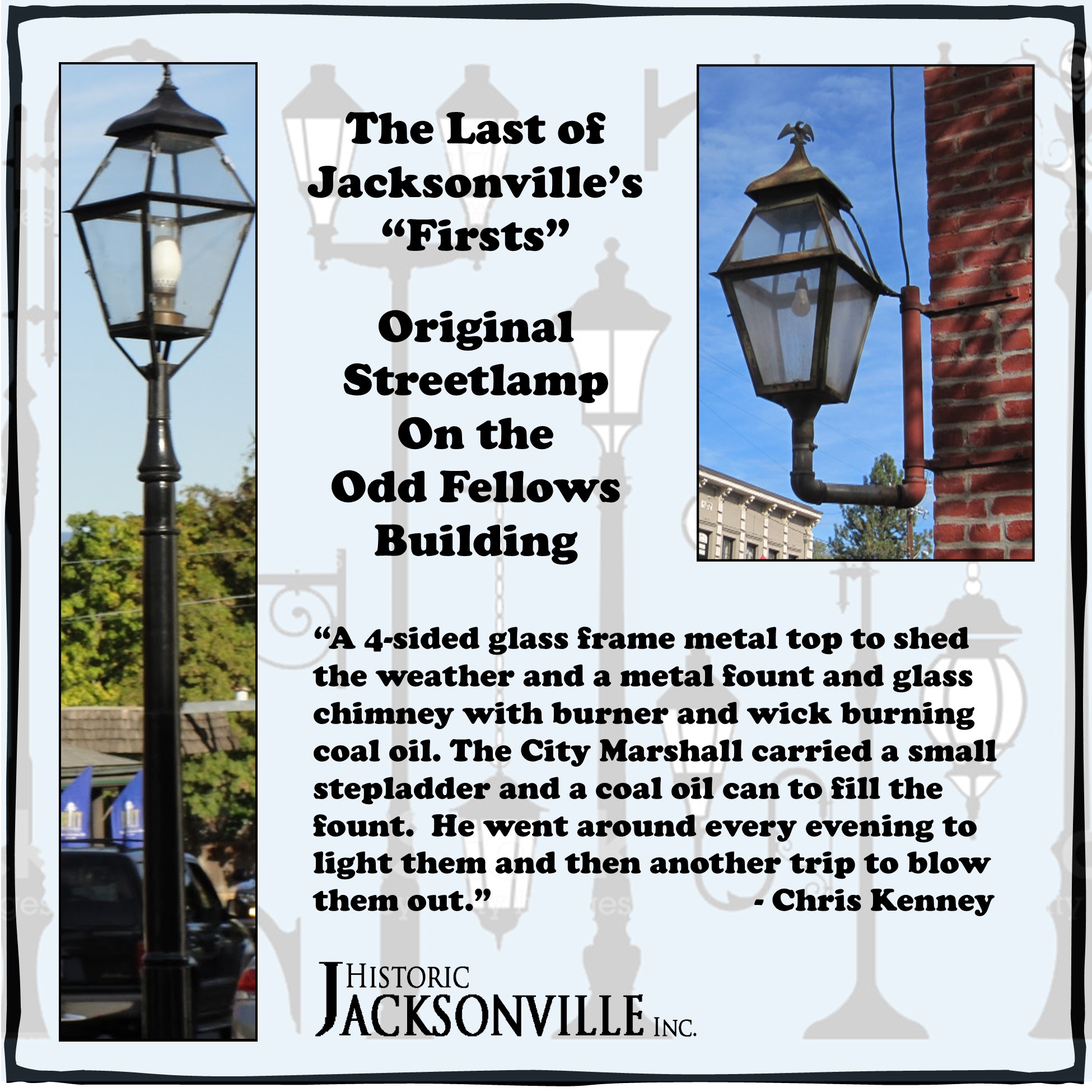

Street Lamps

Historic Jacksonville, Inc. has reached the last of our series of Jacksonville, Oregon, “firsts”! The streetlamps that light many town intersections are reproductions similar to the originals. However, according to Chris Kenney, the town’s original lighting was mounted on buildings (and may have been mounted on poles depending on the definition of “posts”). Chris was the grandson of Daniel M. Kenney who had opened the town’s first trading post in 1852, a tent structure at the corner of Oregon and California streets.

An 83-year-old Chris describes the lights in his 1966 Memoirs: “The original street lights consisted of a post on various corners with 4 sided glass frame metal top to shed the weather and a metal fount and glass chimney with burner and wick burning coal oil. The City Marshall carried a small stepladder and a coal oil can to fill the fount. He went around every evening to light them and then another trip to blow them out. One of the old glass cases adorns the corner of the Odd Fellows Hall, today electrified.”

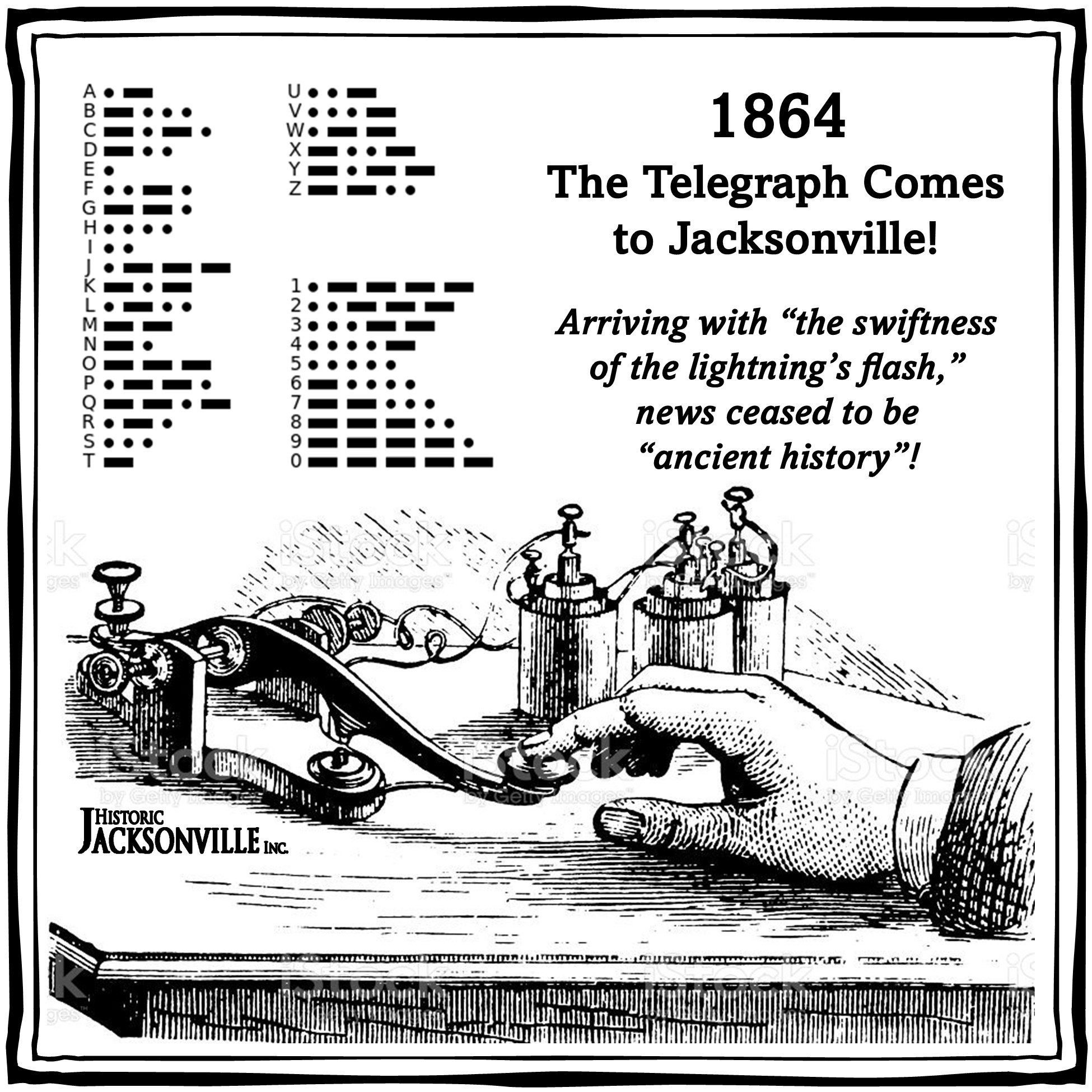

Telegraph Arrives

Prior to the coming of the telegraph, news was transmitted by mail that was carried by travelers, pony express, and then stages. The news could be weeks, even months, old before it reached Jacksonville. Even after Samuel Morse invented the telegraph in the 1830s and created the dot-dash-space Morse code to represent letters, numbers, and punctuations, it was May 24, 1844, before the first message was sent between Baltimore and Washington, D.C.— “What hath God wrought?” It was another 17 years before the first transcontinental telegraph system was completed, and 2 years more before Oregon and Jacksonville were linked to the telegraph.

Multiple challenges delayed the installation. The country was in the middle of the Civil War. The ship carrying the wire for the Oregon telegraph was wrecked off the coast; 200 miles of wire was lost and had to be reordered. Ownership of the telegraph rights changed hands. And once the telegraph reached as far as Yreka, the connecting line to Southern Oregon had to be strung over the Siskiyous.

Finally, by early December, the telegraph wire stretched within 20 miles of Jacksonville—only to have a major storm demolish 80 miles of the line. It was late January of 1864 before Jacksonville was finally connected by telegraph with Yreka. On January 22, 1864, the first message between California and Oregon was finally received.

Some years later, Judge William Colvig recalled the difference the telegraph made. “Before that, news generally was ancient history before it reached us, and it certainly relieved the monotony of pioneer life when news started coming with the swiftness of the lightning’s flash.”

Tom Thumb

On October 4, 1869, Jacksonville was agog! Charles Sherwood Stratton, the most famous superstar of his time, would be appearing at Horne’s Hall that night along with his troup of entertainers. You might be more familiar with Stratton’s stage name—General Tom Thumb. And you would know Horne’s Hall under its official designation—the U.S. Hotel, the wooden predecessor to the 1880 brick structure we know today.

Standing 2’ 11” tall when fully grown, Stratton had been discovered by P.T. Barnum when Stratton was 5-years-old. Barnum taught the boy how to sing, dance, mime, exchange comic banter, and impersonate famous people. Stratton became an international celebrity, a favorite of Queen Victoria, and changed the perception of the public towards “human curiosities,” making them one of the most popular forms of 19th Century U.S. entertainment.

Stratton’s 1863 marriage to Lavinia Warren, another “little person” became front page news, knocking the Civil War off the front page of the “New York Times” for 3 days straight. Warren’s sister, Minnie, and another Barnum performer, “Commodore” George Washington Morrison Nutt, were their attendants. 10,000 guests attended their wedding reception at New York’s Metropolitan Hotel and the couple was subsequently entertained by President and Mrs. Lincoln at the White House.

The Strattons, along with Minnie Warren and Commodore Nutt, toured the world. How they came to perform in Jacksonville is unknown. The “Oregon Sentinel” reported that “the quartet gave a beautiful performance of songs, duets, comic acts, burlesque and laughable eccentricities” but also wondered “at the audacity of such little souls coming on so long a journey.”

Voting

In 1789, the U.S. Constitution gave property-owning or tax-paying white males the right to vote—only 6% of the population. It was another 67 years (1856) before most states adopted universal white male suffrage. In 1870 the 15th Amendment to the Constitution prevented states from denying males the right to vote on grounds of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude”—but it did not prevent them from disenfranchising racial minorities and poor white voters through poll taxes, literacy tests, grandfather clauses, and other restrictions applied in a discriminatory manner.

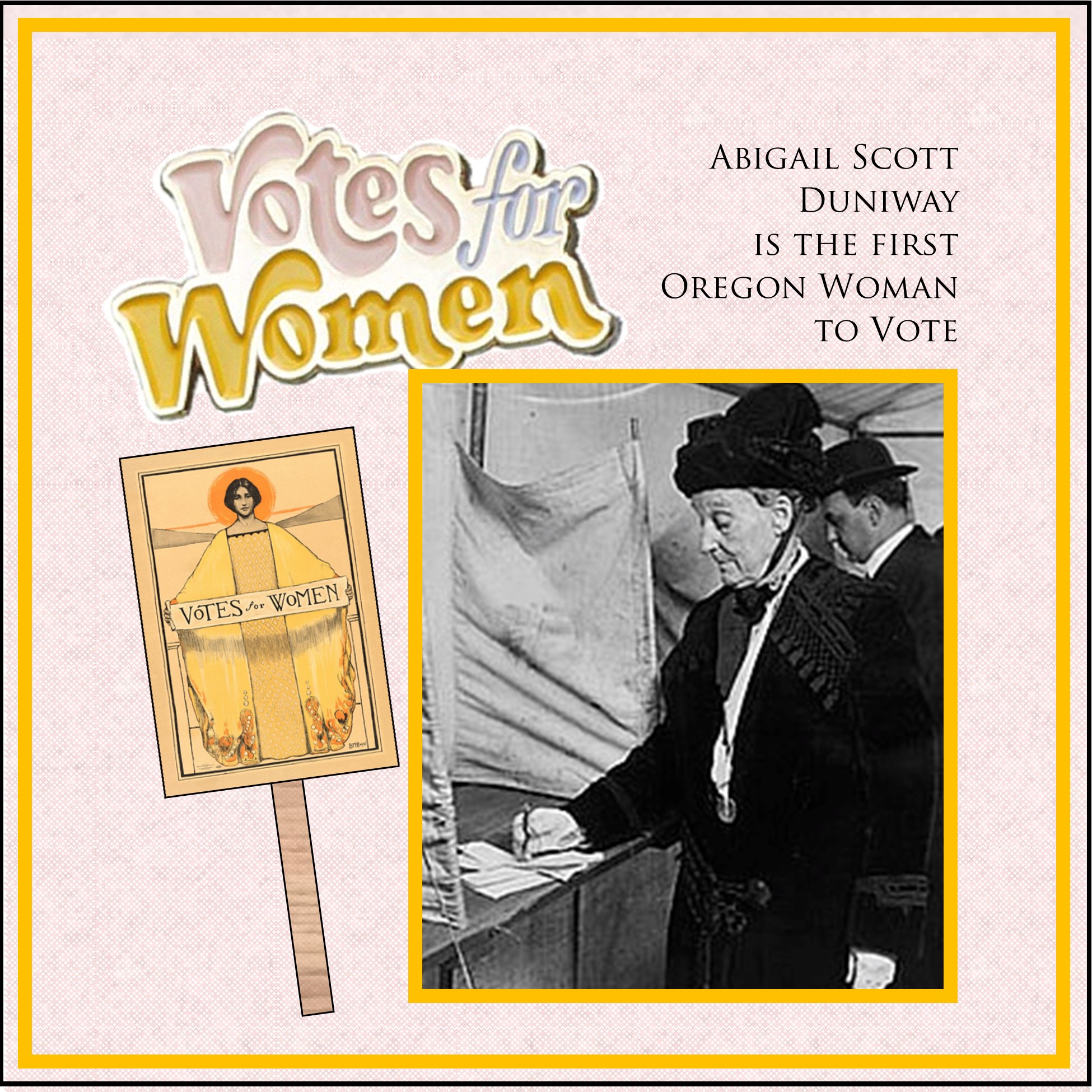

Oregon gave women the right to vote in state elections in 1912, but it was 1920—8 years later and 100 years ago—when the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified giving (white) women the right to vote in national elections as well.

In 1964, poll taxes were prohibited as a condition of voting and in 1965, the Federal Voting Rights Act protected voter registration and voting rights for minorities. But that did not eliminate voter discrimination with some states still choosing to limit polling places, voting hours, and access to absentee ballots among other things. In 1971, voting age was lowered to 18—if you were old enough to fight for your country, you were old enough to vote. And in 1986, service personnel and U.S. citizens living overseas were given the right to vote in federal elections.

On November 7, 2000, Oregon became the nation’s 1st all vote-by-mail state—if you have an address, you receive a ballot. However, in 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act, paving the way for states and jurisdictions to enact restrictive voter identification laws. 23 states created new obstacles to voting. Oregon did the opposite. In 2016, Oregon’s Motor Voter Law took effect, automatically registering to vote anyone applying for or renewing a driver’s license.

As individuals, we may have different visions of what we want our future to be, but Oregon has chosen not to limit our citizens’ participation in the conversation about that future. Historic Jacksonville looks forward to a time when we will again be able to talk—and listen—to each other in search of the unity and compromise that made us the United States of America.

Well at Beekman Bank

The well alongside C.C. Beekman’s Bank was “rediscovered” in 2004 when California Street was rebuilt. And while it may have provided drinking water for downtown shops and stock animals according to the interpretive sign, it was a little more self-serving than that.

Fire was the big hazard in early Jacksonville with fires wiping out major portions of the town during its first 40 years. Beekman was the one who had both the well dug and the pump installed in 1868 to protect his Express building and other commercial investments. The “Oregon Sentinel” newspaper tracked his progress.

October 10, 1868: “Mr. C. C. Beekman has commenced to dig a well on the Express corner and has on the way a large force pump, capable of throwing water over the whole block, which he intends placing in it. We are glad to see a little public spirit left among our citizens, as the majority of them seem inclined to take no precautionary measures.”

October 24, 1868: “The new well of Mr. C. C. Beekman on the Express corner is finished. A good supply of water was struck at 27 feet, about ten of which was through the bedrock. Mr. Beekman intends putting one of the new American submerged pumps in it, which in case of fire will be a great protection. Mr. Beekman deserves credit for his public spirit, and we would be glad to see others do likewise.”

December 5, 1868: “The new submerged pump just placed in the well of C. C. Beekman at the Express Corner is a success. It will throw a stream of water across the street to the roof of Horne’s Hotel and can never freeze up.” The local suppliers of this American Submerged Pump, Hoffman & Klippel, subsequently touted its benefits—” It never freezes, will force water over any building, is invaluable for irrigating, and will not get out of order”—noting that one could be seen in use at the Express corner.

Thanks to Beekman’s foresight and his well and pump, his 1863 Bank/Express office is Jacksonville’s oldest wooden commercial building still standing on California Street despite the town’s many subsequent fires!

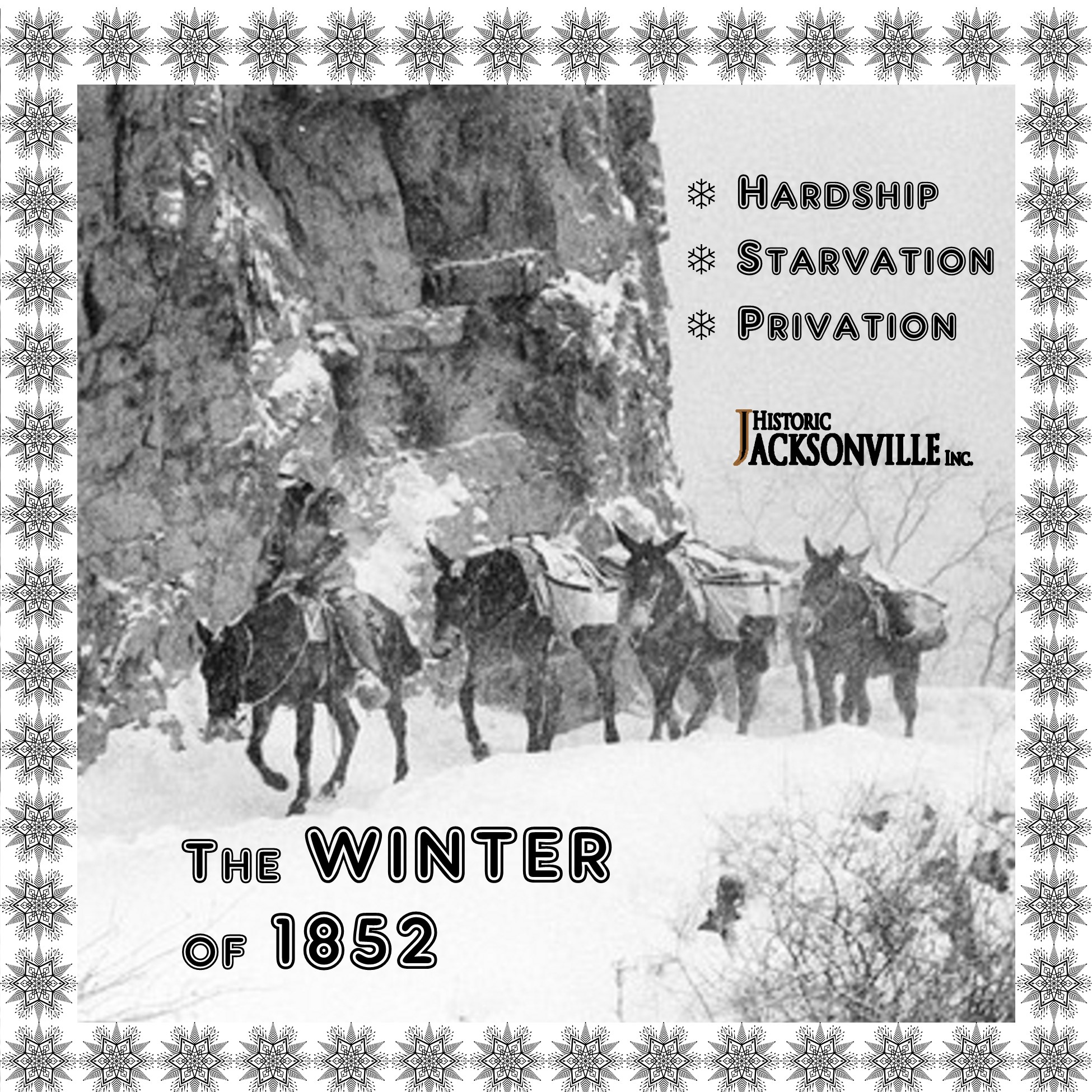

Winter of 1852

The remnants of our recent 8-inch plus snowfall (December 28, 2021) had Historic Jacksonville, Inc. thinking about the winter of 1852—also known locally as “the winter of hardship, starvation, and privation.” Since the discovery of gold earlier that year, both miners and settlers had poured into the Rogue Valley. Population estimates were as high as 10,000. As this influx of new arrivals scrambled to stake claims and build shelters, winter broke hard and mean. By early December the snow was piling up—2 ½ feet deep in the valley; 10 feet deep over the mountain passes. All the trails were blocked; travel was cut off.

Of course no one had anticipated this kind of winter weather. The merchants had no extra goods; few of the miners had stocked up for winter; newcomers who had just crossed the Oregon Trail had only their remaining supplies; and those who had arrived a year earlier had been able to produce only a very limited quantity of food or merchandise, certainly not enough to meet the demand. Prices skyrocketed. By year end, there was no more beef or gunpowder to be had. Salt was literally worth its weight in gold and not to be had even at that price.